Premed students should prepare themselves to compassionately handle the inevitability of patient deaths.

Most prospective medical school students set out to become physicians because they want to heal the sick, often forgetting that patients, young and old, sometimes die. Death is a very real – and natural – part of medicine that you will not only face, but also need to learn how to handle.

Before you start med school, consider how you might care compassionately for a dying patient and how you will cope with losing patients. Although some specialties may be more insulated from death than others, all will be touched by death beginning in med school.

This year, because of the coronavirus pandemic, many premeds will have experiences with family or friends’ families where they will not able to be with the loved one at the time of death. This is hard on everyone involved. Time to grieve together is important to us as human beings.

Some physicians – although very few in my experience – look at death as defeat and cope by emotionally running away from dying patients. For example, in the inpatient setting, they may visit the patient less often or avoid contact altogether.

Currently, patients who die quickly in the intensive care unit have nurses helping them make a final call to their family if they are awake and aware. It has been tremendously difficult for those doctors and nurses in the hospital to go through this process over and over again with their patients so frequently.

Our daughter in Southern California recently was devastated after losing four of her patients to COVID-19 in the same day. I never experienced that in my long career and wonder how I would have handled that and who I would have called on for support. To keep functioning for the next patient, one must find ways to cry, grieve, share and keep moving.

In the outpatient setting, a physician uncomfortable talking about death might recommend a longer time between visits or, rather than suggest a follow-up appointment, wait for the patient to request one. This coping strategy makes patients feel abandoned.

Most doctors are sensitive and some go to the patient’s residence or nursing home to say their final good-bye. I recently read a humanitarian essay by a physician who did just that. You could discern it had been helpful to both the doctor and the patient to have some final moments together.

Other physicians – again, very few in my experience – cope by behaving callously or indifferently. Subconsciously, they may be trying to avoid emotional involvement, but their behavior leaves their patients and the patients’ families feeling hurt and disappointed.

Most physicians find healthy strategies to support their dying patients. These same strategies help physicians keep themselves emotionally healthy, too. However, this year it has required much more. Sharing the emotional pain with a significant other, parent, another physician or a therapist while omitting confidential patient information can be critical.

If you have had the opportunity to talk with front-line caregivers recently, you will quickly sense the difference in how they are coping. For some, the burden of anxiety, depression or burnout is seeping into their normal level of resilience. After almost a year of a deadly pandemic, it is no wonder.

Several med school applicants who had volunteered in these settings continued with patients after COVID-19 hit by phone calls, letters, FaceTime or even Zoom. I was impressed that their caring was authentic and they considered how important it was for the patient that someone continued to reach out when he or she could have simply stopped communicating and used the pandemic as an excuse. This was an important experience for both the patient and the student applicant, not just some ploy to attract the interest of an admissions screener.

As a future med student, it’s vital that you prepare yourself to compassionately face death and dying and the complex emotions that follow. One way to do this is by volunteering after the coronavirus pandemic ends in a hospice facility or nursing home and honing the following seven skills. You can then call on this experience in the future as a physician.

Be Authentic

As a volunteer after COVID, introduce yourself and express your hope that someday you wish to become a physician. Let patients know you are there to learn more about their experiences. Your wish to get acquainted can be a useful conversation starter. Inquire about their experiences when they were growing up or what they were thinking about when they were your age. Ask about their work or career – a generally safe place emotionally – and where they have lived or about their family.

Be sure to make eye contact if you are in person or on FaceTime, and watch your body language. You’ll use these skills when you’re a physician to engender trust and open communication with your patients.

Listen With Purpose

Practice your active listening skills so that during future visits you can ask patients more about what they told you previously. By bringing up something from a past visit, you will show that you remembered what they told you and that they matter to you as a person. Active listening is another skill you will use throughout your medical career and can start cultivating right now, even during the pandemic.

Allow Patients to Talk About Death

Everyone faces death differently. Some people want to talk about it while others prefer to reflect on their life and accomplishments. Whether now as a volunteer or later as a physician in training, let patients talk about death as they need to. Don’t shut down the conversation by saying, “Everything will be all right.” Instead, ask them to tell you more. Listen to all they have to say, whether it’s about their health, fears or fond memories.

This can be very hard, maybe even harder with someone in your own family. You will want them to keep fighting and may be tempted to cut into the conversation to encourage them to keep fighting. Sadly, I learned this the hard way with my own mother. We eventually got around to the hard discussions, but we could have had many richer conversations if I had just listened.

Visit or Connect By Phone or FaceTime Consistently

A good physician builds rapport over time, and you can develop this skill through your volunteer position. Visit patients if you are able. If there are long gaps between your visits, drop the patient a note or call to check in.

This is a good habit to develop so that when you are a physician, your patients – particularly those who are dying – will feel supported. At the end of each visit, thank the patients. You won’t know at the time if it will be your last opportunity to visit with them, so treasure each interaction.

Do Your Homework

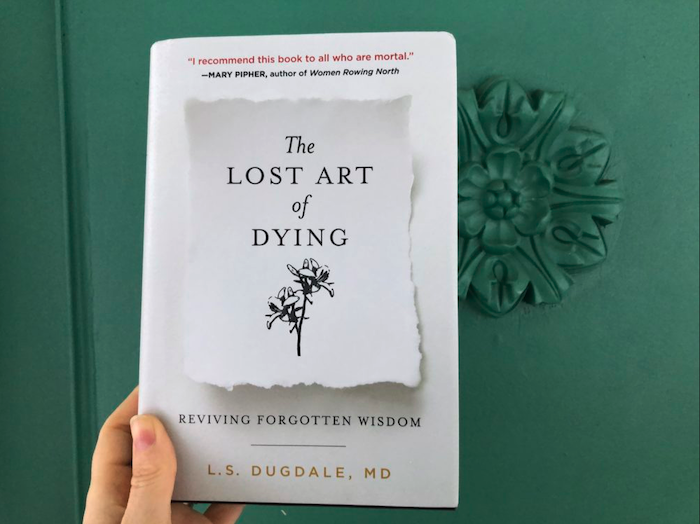

Myriad scholarly articles and books are available to help physicians, and all people, accept that death is an inevitable part of life and that grieving is not only normal but encouraged.

Decades ago, Dr. Elisabeth Kubler-Ross wrote about the five stages of grief. We now understand that people don’t necessarily experience the five stages in order; rather, the stages often fluctuate. Most people can describe their shock, anger, depression, negotiation, disbelief and acceptance following a loved one’s death. Some get stuck between anger and depression.

After the initial feeling of loss has abated, most people begin remembering the fun times and reflecting on fond memories. The ones who have inspired me still see the good in life and want to share love, even at the end. Don’t be afraid to cry. If tears begin to flow, patients do not see that as weakness but rather that you sincerely care about them and what they are going through in this process.

Connect With the Social Work Team

Social workers deal with death and dying regularly and can give you advice about how they cope and prevent burnout. For instance, attending the funeral helps some people. Others seek solace from support groups or counseling.

If you’re at a hospital, make the social work team part of your professional network. Their support and advice will help you cope as a physician, especially when you lose a patient who had a particular influence on you.

Allow Yourself to Grieve

Over the course of your relationships with patients who are dying, you will learn a great deal about your capacity to care for another person. When patients die, it will hurt and you will gain some insight about your ability to cope. Physicians often cope by speaking confidentially with colleagues and expressing sadness and other emotions in a journal. After omitting a patient’s protected health information, some physicians publish their writings to help themselves and others who are grieving.

Many medical schools teach students to reflect on their emotions and write them down. Writing and seeing the words help the healing process. Remember that everyone grieves differently. Give yourself the room to process your emotions and to discover the coping mechanism that’s right for you. Writing a note of condolence to a deceased patient’s family via the funeral home or newspaper obituary can be helpful to you and the family.

As a future medical student, embrace the opportunity to get to know someone who is dying. Your experiences will allow you to reflect about how you will feel when one of your future patients dies and will create a meaningful bond between you and the people you touch – now and in the future.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!