By James Hamblin, MD

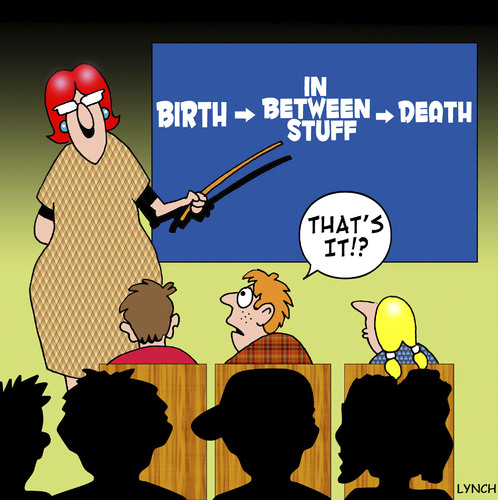

Dr. Ezekiel Emanuel, oncologist and chair of the Department of Bioethics at the National Institutes of Health (and, entirely incidentally, brother to Rahm and Ari Emanuel) has long been a champion of end-of-life care. He spoke today with Corby Kummer at The Atlantic’s Washington Ideas Forum, where he made succinct points about strategies for systematic improvements in our approach to caring for those nearest to death.

First, all doctors and nurses should be formally trained in end-of-life care and discussions. Walking into a room with a patient and their family to discuss a terminal diagnosis or prognosis is — especially at first — overwhelming, and impossible to just know how to do. Emanuel admits that facing those situations remains “scary,” even as a veteran clinician. He and most of his generation of physicians never received formal training in how to best discuss terminal illness with patients and offer palliative options, and some in training today still do not. Considering the large number of people who eventually face death, it is unreasonable that not all doctors and nurses are thoroughly prepared to help them as they do.

First, all doctors and nurses should be formally trained in end-of-life care and discussions. Walking into a room with a patient and their family to discuss a terminal diagnosis or prognosis is — especially at first — overwhelming, and impossible to just know how to do. Emanuel admits that facing those situations remains “scary,” even as a veteran clinician. He and most of his generation of physicians never received formal training in how to best discuss terminal illness with patients and offer palliative options, and some in training today still do not. Considering the large number of people who eventually face death, it is unreasonable that not all doctors and nurses are thoroughly prepared to help them as they do.

Emanuel also cited that more than 40 percent of hospitals in the U.S. do not offer access to palliative care, either within the hospital or after a patient has been discharged home. He believes that hospitals should be required to at least offer the option.

And finally, at present, eligibility for hospice care is predicated on having six months to live. Emanuel sees access to hospice as more aptly need-based, not calendar-based. Patients with symptoms warranting palliation, regardless of the estimated length of their remaining life, should be standardly offered care in that vein.

All of these changes would come as part of an ongoing shift in psychology and broader openness about death. Emanuel is quick to add the caveat that he is not talking about euthanasia or [shudder] … “death panels.” His inclination toward explicit clarification on that point stems from accusations that he and other leaders in the realm of end-of-life care have endured in the past. The fact that he still needs to make that clarification speaks to the persistent widespread misunderstanding surrounding quality end-of-life care. That mindset is and will remain the primary barrier to seeing these improvements out.

Complete Article HERE!