By Robert Kastenbaum

What is the good life? Most people would prefer health to illness, affluence to poverty, and freedom to confinement. Nevertheless, different people might have significantly different priorities. Is the good life one that is devoted to family affection or individual achievement? To contemplation or action? To safeguarding tradition or discovering new possibilities? There is a parallel situation in regard to the good death. Not surprisingly, most people would prefer to end their lives with ease of body, mind, and spirit. This unanimity dissolves, however, when one moves beyond the desire to avoid suffering. Societies as well as individuals have differed markedly in their conception of the good death. The long and eventful history of the good death has taken some new turns at the turn of the millennium, although enduring links with the past are still evident.

Dying is a phase of living, and death is the outcome. This obvious distinction is not always preserved in language and thought. When people speak of “the good death,” they sometimes are thinking of the dying process, sometimes of death as an event that concludes the process, and sometimes of the status of “being dead.” Furthermore, it is not unusual for people to shift focus from one facet to another.

Dying is a phase of living, and death is the outcome. This obvious distinction is not always preserved in language and thought. When people speak of “the good death,” they sometimes are thinking of the dying process, sometimes of death as an event that concludes the process, and sometimes of the status of “being dead.” Furthermore, it is not unusual for people to shift focus from one facet to another.

Consider, for example, a person whose life has ended suddenly in a motor vehicle accident. One might consider this to have been a bad death because a healthy and vibrant life was destroyed along with all its future possibilities. But one might also consider this to have been a good death in that there was no protracted period of suffering. The death was bad, having been premature, but the dying was merciful. Moreover, one might believe that the person, who is now “in death,” is either experiencing a joyous afterlife or simply no longer exists.

It is possible, then, to confuse oneself and others by shifting attention from process to event to status while using the same words. It is not only possible but also fairly common for these three aspects of death to be the subject of conflict. For example, the controversial practice of physician-assisted suicide advances the event of death to reduce suffering in the dying process. By contrast, some dying people have refrained from taking their own lives in the belief that suicide is a sin that will be punished when the soul has passed into the realm of death. It is therefore useful to keep in mind the distinction between death as process, event, and status. It is also important to consider perspective: who judges this death to be good or bad? Society and individual do not necessarily share the same view, nor do physician and patient.

Philosophers continue to disagree among themselves as to whether death can be either good or bad. The Greek philosopher Epicurus (341–270 B.C.E.) made the case that death means nothing to us one way or the other: When we are here, death is not. When death is here, we are not. So why worry? Subsequent philosophers, however, have come up with reasons to worry. For example, according to Walter Glannon, author of a 1993 article in the journal Monist, the Deprivation of Goods Principle holds that death is bad to the extent that it removes the opportunity to enjoy what life still might have offered. It can be seen that philosophers are talking past each other on this point. Epicurus argued that death is a matter of indifference because it is outside humans’ lived experience. This is a focus on process. Glannon and others argue that the “badness” of death is relative and quantitative—it depends on how much one has lost. This is a focus on death as event.

A World Perspective

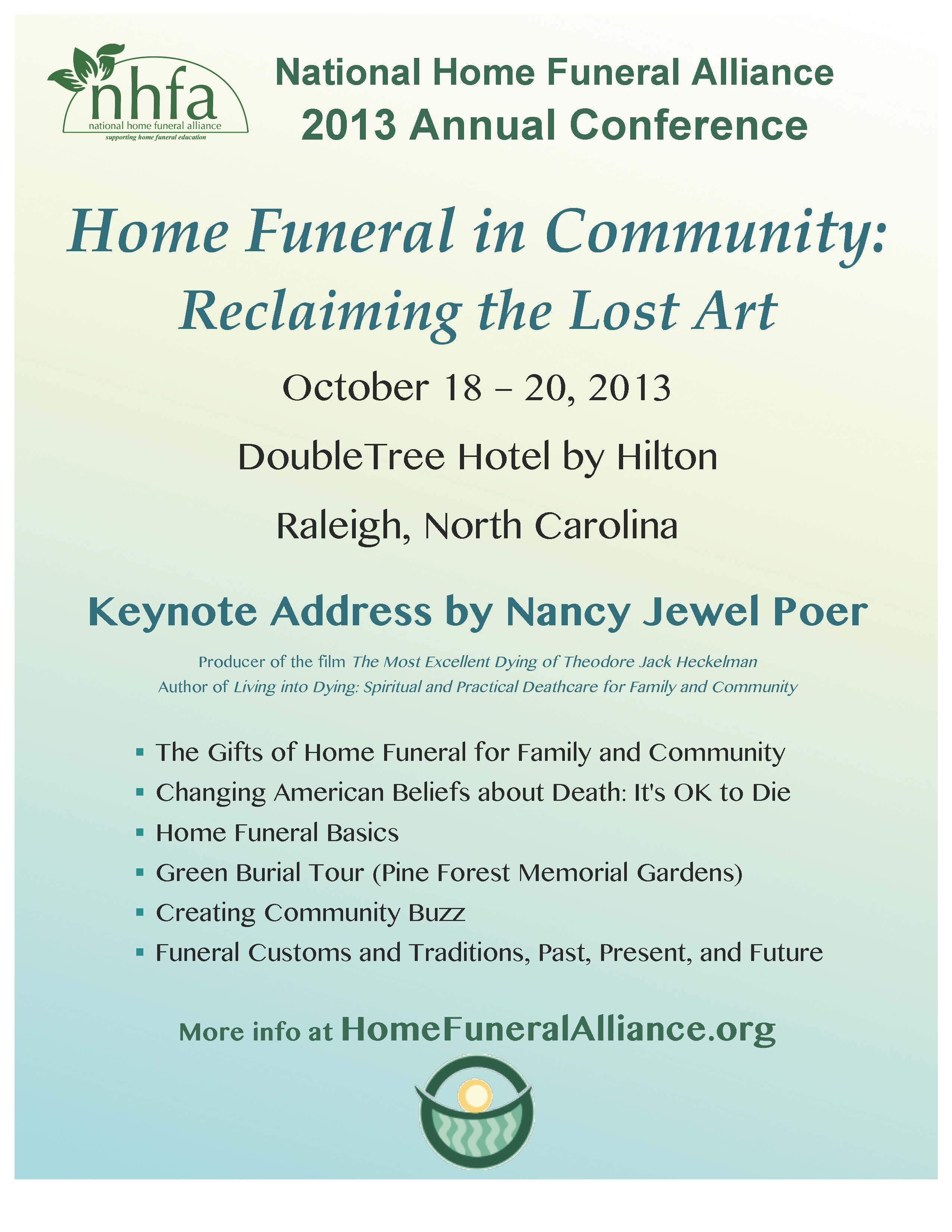

From terminology and philosophy, one next turns to the rich heritage of world cultures as they have wrestled with the question of the good death within their own distinctive ways of life. Many of the world’s peoples have lived in fairly small groups. People knew each other well and were bonded to their territory by economic, social, and religious ties. These face-to-face societies often contended with hardships and external threats. Community survival was therefore vital to individual survival. Within this context, the good death was regarded as even more consequential for the community than for the individual.

The good death was one that did not expose the community to reprisals from angry spirits or stir up confusion and discontent among the survivors. Personal sorrow was experienced when a family member died, but the community as a whole responded with a sequence of rituals intended to avoid the disasters attendant on a bad death.

The Lugbara of Uganda and Zaire do not practice many rituals for birth, puberty, or marriage, but they become intensely involved in the funeral process. Death is regarded as an enemy, an alien force that raids the village. Nobody just dies. Much of Lugbara life is therefore devoted to controlling or placating evil spirits. The good death for the Lugbara encompasses the process, the event, and the state.

- The Process: Dying right is a performance that should take place in the individual’s own hut with family gathered about to hear the last words. The dying person should be alert and capable of communicating, and the final hours should flow peacefully without physical discomfort or spiritual distress. The dying person has then prepared for the passage and has settled his or her affairs with family and community. It is especially desirable that a lineage successor has been appointed and confirmed to avoid rivalry and perhaps violence.

- The Event: The death occurs on schedule—not too soon and not too much later than what was expected. The moment is marked by the lineage successor with the cre, a whooping cry, which signifies that the deceased is dead to the community both physically and socially, and that the people can now get back to their lives.

- The State: The deceased and the community have performed their ritual obligations properly, so there is little danger of attack from discontented spirits. The spirit particular to the deceased may linger for a while, but it will soon continue its journey through the land of the dead.

- A death can go bad when any of these components fails. For example, a person who dies suddenly or away from home is likely to become a confused and angry spirit who can become a menace to the community. A woman who dies in childbirth might return as an especially vengeful spirit because the sacred link between sexuality and fertility has been violated. The Lugbara deathbed scene shows compassion for the dying person and concern for the well-being of the community. Nevertheless, it is a tense occasion because a bad death can leave the survivors vulnerable to the forces of evil.

In many other world cultures the passage from life to death has also been regarded as a crucial transaction with the realm of gods and spirits. The community becomes especially vulnerable at such times. It is best, then, to support this passage with rules and rituals. These observances begin while the person is still alive and continue while the released spirit is exploring its new state of being. Dying people receive compassionate care because of close interpersonal relationships but also because a bad death is so risky for the community.

Other conceptions of the good death have also been around for a long time. Greek, Roman, Islamic, Viking, and early Christian cultures all valued heroic death in battle. Life was often difficult and brief in ancient times. Patriotic and religious beliefs extolled those who chose a glorious death instead of an increasingly burdensome and uncertain life. Norse mythology provides an example made famous in an opera by the nineteenth-century German composer Richard Wagner in which the Valkyrie—the spirits of formidable female warriors—bring fallen heroes to Valhalla where their mortal sacrifice is rewarded by the gods.

Other conceptions of the good death have also been around for a long time. Greek, Roman, Islamic, Viking, and early Christian cultures all valued heroic death in battle. Life was often difficult and brief in ancient times. Patriotic and religious beliefs extolled those who chose a glorious death instead of an increasingly burdensome and uncertain life. Norse mythology provides an example made famous in an opera by the nineteenth-century German composer Richard Wagner in which the Valkyrie—the spirits of formidable female warriors—bring fallen heroes to Valhalla where their mortal sacrifice is rewarded by the gods.

Images of the heroic death have not been limited to the remote past. Many subsequent commanders have sent their troops to almost certain death, urging them to die gloriously. The U.S. Civil War (1861–1865) provides numerous examples of men pressing forward into withering firepower, but similar episodes have also occurred repeatedly throughout the world. Critics of heroic death observe that the young men who think they are giving their lives for a noble cause are actually being manipulated by leaders interested only in their own power.

Some acts of suicide have also been considered heroic. The Roman commander who lost the battle could retain honor by falling on his sword, and the Roman senator who displeased the emperor was given the opportunity to have a good death by cutting his wrists and bleeding his life away. Japanese warriors and noblemen similarly could expiate mistakes or crimes by the ritualistic suicide known in the West as hara-kiri. Widows in India were expected to burn themselves alive on their husbands’ funeral pyres.

Other deaths through the centuries have earned admiration for the willingness of individuals to sacrifice their lives to help another person or affirm a core value. Martyrs, people who chose to die rather than renounce their faith, have been sources of inspiration in Christianity and Islam. There is also admiration for the courage of people who died at the hands of enemies instead of betraying their friends. History lauds physicians who succumbed to fatal illnesses while knowingly exposing themselves to the risk in order to find a cause or cure. These deaths are exemplary from society’s perspective, but they can be regarded as terrible misfortunes from the standpoint of the families and friends of the deceased.

The death of the Greek philosopher Socrates (c. 470–399 B.C.E.) shines through the centuries as an example of a person who remained true to his principles rather than take an available escape route. It is further distinguished as a death intended to be instruction to his followers. The good death, then, might be the one that strengthens and educates the living. The modern hospice/palliative care movement traces its origins to deaths of this kind.

With the advent of Christianity the stakes became higher for the dying person. The death and resurrection of Jesus led to the promise that true  believers would also find their way into heaven—but one might instead be condemned to eternal damnation. It was crucial, then, to end this life in a state of grace. A new purification ritual was developed to assist in this outcome, the ordo defunctorum. The last moments of life now took on extraordinary significance. Nothing less than the fate of the soul hung in the balance.

believers would also find their way into heaven—but one might instead be condemned to eternal damnation. It was crucial, then, to end this life in a state of grace. A new purification ritual was developed to assist in this outcome, the ordo defunctorum. The last moments of life now took on extraordinary significance. Nothing less than the fate of the soul hung in the balance.

The mood as well as the practice of Christianity underwent changes through the centuries with the joyful messianic expectation of an imminent transformation giving way to anxiety and doubt. The fear of punishment as a sinner darkened the hope of a blissful eternity. Individual salvation became the most salient concern. By the fifteenth century, European society was deeply immersed in death anxiety. The Ars Moriendi (“art of dying”) movement advised people to prepare themselves for death every day of their lives—and to see that their children learned to focus on the perils of their

own deathbed scene rather than become attached to the amusements and temptations of earthly life. The good death was redemption and grace; everything else was of little value.

This heavy emphasis on lifelong contemplation of mortality and the crucial nature of the deathbed scene gradually lessened as the tempo of sociotechnological change accelerated. Hardships continued, but earthly life seemed to offer more attractions and possibilities, drawing attention away from meditations on death. And by the seventeenth century a familiar voice was speaking with a new ring of authority. Physicians were shedding their humble roles in society and proudly claiming enhanced powers and privileges. In consequence, the nobility were more likely to be tormented by aggressive, painful, and ineffective interventions before they could escape into death. The emerging medical profession was staking its claim to the deathbed scene. It was a good death now when physicians could assure each other, “We did everything that could be done and more.”

The Good Death in the Twenty-First Century

In the early twenty-first century, as in the past, humans seek order, security, and meaning when confronted with death. It is therefore clear that not everything has changed. Nevertheless, people’s views of the good death have been influenced by the altered conditions of life. To begin with, there are more people alive today than ever before, and, in technologically developed nations, they are more likely to remain alive into the later adult years. The most remarkable gains in average life expectancy have come from eliminating the contagious diseases that previously had killed many infants and children. The juvenile death rate had been so high that in various countries census takers did not bother to count young children. Parents mourned for their lost children then as they do now. The impact of this bad death was tempered to some extent by the knowledge that childhood was perilous and survival in God’s hands. The current expectation that children will certainly survive into adulthood makes their death even more devastating. Parental self-blame, anger at God, stress disorders, and marital separation are among the consequences that have been linked to the death of a child.

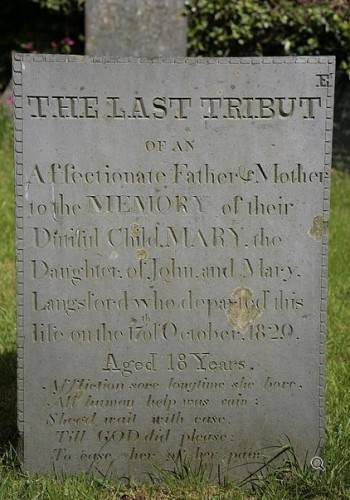

Childbirth was a hazardous experience that many women did not long survive. Graveyards around the world provide evidence in stone of young mothers who had soon joined their infants and children in death. Such deaths are much less expected in the twenty-first century and therefore create an even bigger impact when they do occur.

In the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, many Mexicans died while attempting to cross the desert to find employment in the United States in order to feed and shelter their families. Are these “good deaths” because of the heroism of those who risked—and lost—their lives, tragic deaths because of their consequences, or senseless deaths because society has allowed this situation to develop?

It is far more common to assume that one has the right to a long life and therefore to regard an earlier demise as unfair or tragic. Paradoxically, though, there is also more concern about not dying young. Many people remain vigorous and active through a long life. Nevertheless, gerontophobia (fear of growing old) has become a significant problem in part because more people, having lived long, now die old. Younger people often fear that age will bring them to a lonely, dependent, and helpless preterminal situation. The distinction between aging and dying has become blurred in the minds of many people, with aging viewed as a slow fading away in which a person becomes less useful to themselves and others. It is a singularly prolonged bad death, then, to slide gradually into terminal decline, in essence having outlived one’s authentic life. This pessimistic outlook has been linked to the rising rate of suicide for men in older age groups. In reality, many elders both contribute to society and receive loving support until the very end, but the image of dying too long and too late has become an anxious prospect since at least the middle of the twentieth century.

Two other forms of the bad death came to prominence in the late twentieth century. The aggressive but mostly ineffective physicians of the seventeenth century have been replaced by a public health and medical establishment that has made remarkable strides in helping people through their crises. Unfortunately, some terminally ill people have experienced persistent and invasive medical procedures that produced suffering without either extending or restoring the quality of their lives. The international hospice movement arose as an alternative to what was seen as a futile overemphasis on treatment that added to the physical and emotional distress of the dying person. The hospice mission has been to provide effective symptom relief and help the dying person maintain a sense of security and worth by supporting the family’s own strength.

Two other forms of the bad death came to prominence in the late twentieth century. The aggressive but mostly ineffective physicians of the seventeenth century have been replaced by a public health and medical establishment that has made remarkable strides in helping people through their crises. Unfortunately, some terminally ill people have experienced persistent and invasive medical procedures that produced suffering without either extending or restoring the quality of their lives. The international hospice movement arose as an alternative to what was seen as a futile overemphasis on treatment that added to the physical and emotional distress of the dying person. The hospice mission has been to provide effective symptom relief and help the dying person maintain a sense of security and worth by supporting the family’s own strength.

Being sustained indefinitely between life and death is the another image of the bad death that has been emerging from modern medical practice. The persistent vegetative state arouses anxieties once associated with fears of being buried alive. “Is this person alive, dead, or what?” is a question that adds the pangs of uncertainty to this form of the bad death.

The range of bad death has also expanded greatly from the perspective of those people who have not benefited from the general increase in life expectancy. The impoverished in technologically advanced societies and the larger part of the population in third world nations see others enjoy longer lives while their own kin die young. For example, once even the wealthy were vulnerable to high mortality rates in infancy, childhood, and childbirth. Many such deaths are now preventable, so when a child in a disadvantaged group dies for lack of basic care there is often a feeling of rage and despair.

A change in the configuration of society has made it more difficult to achieve consensus on the good death. Traditional societies usually were built upon shared residence, economic activity, and religious beliefs and practices. It was easier to judge what was good and what was bad. Many nations include substantial numbers of people from diverse backgrounds, practicing a variety of customs and rituals. There is an enriching effect with this cultural mix, but there is also the opportunity for misunderstandings and conflicts. One common example occurs when a large and loving family tries to gather around the bedside of a hospitalized family member. This custom is traditional within some ethnic groups, as is the open expression of feelings. Intense and demonstrative family gatherings can unnerve hospital personnel whose own roots are in a less expressive subculture. Such simple acts as touching and singing to a dying person can be vital within one ethnic tradition and mystifying or unsettling to another.

Current Conceptions of the Good Death

The most obvious way to discover people’s conceptions of the good death is to ask them. Most studies have focused on people who were not afflicted with a life-threatening condition at the time. There is a clear preference for an easy death. The process should be mercifully brief. Often people specify that death should occur in their sleep. Interestingly, students who are completing death education courses and experienced hospice care-givers tend toward a different view. When their turn comes, they would want to complete unfinished business, take leave of the people most important to them, and reflect upon their lives and their relationship to God. These actions require both time and awareness. Drifting off to sleep and death would be an easy ending, but only after they had enough opportunity to do what must be done during the dying process.

Women often describe their imagined deathbed scenes in consoling detail: wildflowers in an old milk jug; a favorite song being played; familiar faces gathered around; a grandchild skipping carefree in and out of the room; the woman, now aged and dying, easy in mind, leaving her full life without regrets. Conspicuous by their absence are the symptoms that often accompany the terminal phase—pain, respiratory difficulties, and so on. These good deaths require not only the positives of a familiar environment and interpersonal support but also a remarkably intact physical condition. (Men also seldom describe physical symptoms on their imagined deathbed.) Men usually give less detailed descriptions of their imagined final hours and are more likely than women to expect to die alone or suddenly in an accident. The imagined good death for some men and a few women takes place in a thrilling adventure, such as skydiving. This fantasy version of death is supposed to occur despite the ravages of a terminal illness.

What is the good death for people who know that they have only a short time to live? People dying of cancer in the National Hospice Demonstration study conducted in 1988, explained to their interviewers how they would like to experience the last three days of their lives. Among their wishes were the following:

- I want certain people to be here with me.

- I want to be physically able to do things.

- I want to feel at peace.

- I want to be free from pain.

- I want the last three days of my life to be like any other days.

This vision of the good death does not rely on fantasy or miracles. It represents a continuation of the life they have known, and their chances of having these wishes fulfilled were well within the reality of their situation. Religion was seldom mentioned as such, most probably because these people were secure in their beliefs.

Society as a whole is still reconstructing its concepts of both the good life and the good death. Studies suggest that most people hope to be spared pain and suffering, and to end their days with supportive companionship in familiar surroundings. Dramatic endings such as heroic sacrifice or deathbed conversion are seldom mentioned. There are continuing differences of opinion in other areas, however. Should people fight for their lives until the last breath, or accept the inevitable with grace? Is the good death simply a no-fuss punctuation mark after a good life—or does the quality of the death depend on how well people have prepared themselves for the next phase of their spiritual journey? Questions such as these will continue to engage humankind as the conditions of life and death also continue to change over time.

Complete Article HERE!