By Hope

By Hope

[F]rom the peaks of the Blue Ridge and the Great Smoky Mountains, to the river valleys of the French Broad and Catawba, North Carolina has a long history that is steeped in rich Appalachian traditions. Despite the Hollywood “hillbilly” stereotype, Appalachians carry a sense of pride for their culture, language, and heritage.

Isolated from the outside world, Appalachian regions have long struggled with rough rocky terrain for farming and plagued with poverty. Immigrants from Europe began migrating to the area in the 18th century with a large proportion of the population being Ulster Scots and Scotch-Irish. Many pioneers moved into areas largely separated from civilization by high mountain ridges and our pioneer ancestors were rugged, self-sufficient and brought many traditions from the Celtic Old World that is still a part of Appalachian culture today.

If you grew up Appalachian, you usually had a family relative who was gifted and could foresee approaching death, omens or dreams of things to come.

There was always a granny witch to call on when someone was sick and needed special magic for healing. Superstitions about death were common and were considered God’s will. One thing for sure, no matter how hard you fought it, death always won.

Appalachian folks are no stranger to death. For the Dark Horseman visited so frequently, houses were made with two front doors. One door was used for happy visits and the other door, known as the funeral door, would open into the deathwatch room for sitting up with the dead. Prior to the commercialization of the funeral industry, funeral homes and public cemeteries were virtually nonexistent in the early days of the Appalachian settlers.

For Whom the Bell Tolls…

In small Appalachian villages, the local church bell would toll to alert others a death has occurred. Depending on the age of the deceased, the church bell would chime once for every year of their life they had lived on this earth. Family and friends quickly stop what they were doing and gather at the deceased family’s homestead to comfort loved ones. Women in the community would bring food as the immediate family would make funeral preparations for burial. The men would leave their fields to meet together and dig a hole for the grave and the local carpenter would build a coffin based on the deceased loved one’s body measurements.

Due to the rocky terrain, sometimes dynamite was used to clear enough rock for the body to be buried. Coffins used to be made from trunks of trees called “tree coffins”. Over time, pine boxes replaced the tree coffins. They were lined with cloth usually made from cotton, linen or silk and the outside of the coffin was covered in black material. If a person died in the winter, the ground would be too frozen to dig a grave. In this case, the dead would simply be placed in a protected area outdoors until spring.

After the bell tolls, every mirror in the home would be draped with dark cloth and curtains would be closed. It was believed that by covering the mirror, a returning spirit could not use the looking glass as a portal and would cross over into their new life. The swinging hands on the clock were stopped not only to record the time of death, but it was believed that when a person died, time stood still for them.

Preparing the Body

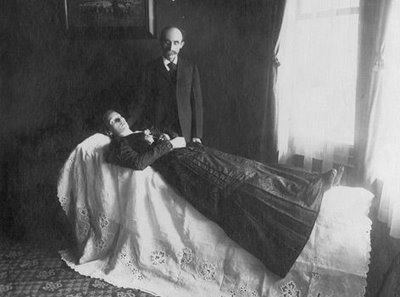

Before the use of embalming, the burial would be the next day since there were no means of preserving the body. To prepare the body, the deceased would be “laid out” and remained in the home until burial. The body would be placed on a cooling board or “laying out” board. Depending on the family, the “laying out” board might be a door taken off the hinges, a table, ironing board or piece of lumber. Many families had a specific board for the purpose of laying out the body that had been passed down from generations.

The “laying out” board would then be placed on two chairs or sawhorses so the body could be stretched out straight. Depending on what position the person was in when they died, sometimes it was necessary to break bones or soak parts of the body in warm water to get the corpse flat on the board. As rigor mortis began to set in, some folks have actually heard bones cracking and breaking which would cause the corpse to move as it began to stiffen. The board would then be covered with a sheet and a rope was used to tie the body down to keep it straight and to prevent it from suddenly jerking upright.

Scottish traditions used the process of saining which is a practice of blessing and protecting the body. Saining was performed by the oldest woman in the family. The family member would light a candle and wave it over the corpse three times. Three handfuls of salt were put into a wooden bowl and placed on the body’s chest to prevent the corpse from rising unexpectedly.

Once the body was laid out, their arms were folded across the chest and legs brought together and tied near the feet. A handkerchief was tied under the chin and over the head to keep the corpse’s mouth from opening. To prevent discoloration of the skin, a towel was soaked in soda water and placed over the face until time for viewing. Aspirin and water were also used sometimes to prevent the dead from darkening. If the loved one died with their eyes open, weights or coins were placed over the eyes to close them.

Silver coins or 50 cent pieces were used instead of pennies because the copper would turn the skin green. Once the corpse was in place, the body would then be washed with warm soap and water. Then family members would dress the loved one in their best attire which was usually already picked out by the person before they passed. The body of the dead is never left alone until it was time to take the deceased for burial.

Sitting Up With the Dead

After the body has been prepared, the body is placed in the handmade coffin for viewing and placed in the parlor or funeral room. The custom of “sitting up with the dead” is also called a “Wake”. Most times a handmade quilt would be placed over the body along with flowers and herbs. The ritual of sending flowers to a funeral came from this very old tradition. The aroma from the profusion of flowers around the deceased helped mask the odor of decomposition.

Flowers as a form of grave decoration were not widely used in the United States until after the mid-nineteenth century. In the Southern Appalachians, traditional grave decorations included personal effects, toys, and other items such as shells, rocks, and pottery sherds. Bunches of wildflowers and weeds, homemade plant or vegetable wreaths, and crepe paper flowers gradually attained popularity later in the nineteenth century. Placing formal flower arrangements on graves was gradually incorporated into traditional decoration day events in the twentieth century.

The day after the Wake, the body would be loaded into a wagon and taken to the church for the funeral service. Family and friends walked behind the wagon all dressed in black. The church bell would toll until the casket was brought into the church. This would be the last viewing as friends and family walked past the casket to take a final look at the body. Some would place a variety of objects in the coffin such as jewelry, tobacco, pipes, toys, a bible and every once in an alcoholic beverage.

Today, a strong sense of community continues to dominate Appalachian burial customs even though the modern funeral industry has changed the customs slightly. The social dimension has changed completely since caskets are commercially produced and graves are seldom dug by hand. Modern funeral homes have made the task of burial more convenient but the downside is there is less personal involvement. Personalized care for the dead is an important aspect of family and community life in Appalachia. And we can certainly say for sure that the days of conducting the entire procedure necessary to bury a person, all done by caring neighbors, with no charge involved, are no longer practiced.

Complete Article HERE!