By Scott Janssen

For months, as I’ve visited Evan as his hospice social worker, he has been praying to die. In his early 90s, he has been dealing with colorectal cancer for more than four years, and he is flat tired out. As he sees it, the long days of illness have turned his life into a tedious, meaningless dirge with nothing to look forward to other than its end. He’s done, finished. He often talks about killing himself.

On this visit, though, his depression seems to have lifted. He’s engaged and upbeat — and this sudden about-face arouses my suspicions: Has he decided to do it? Is he planning a way out?

“You seem to feel differently today than on other visits,” I say casually. “What’s going on?”

He looks at me cryptically.

“Do you believe in ghosts?” he asks.

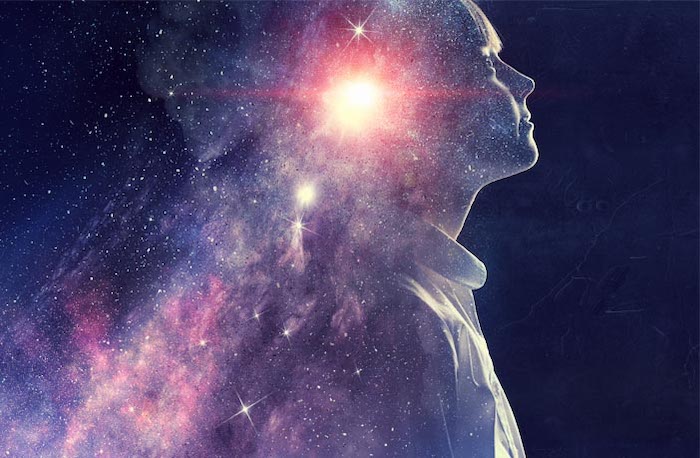

It’s not the first time a patient has asked me this. People can have unusual experiences when they reach the end of life: near-death or out-of-body experiences, visitations from spiritual beings, messages delivered in dreams, synchronicities or strange behaviors by animals, birds, even insects.

“There are all kinds of ghosts,” I respond seriously. “What kind are you talking about?”

“You remember me telling you about the war?” he asks

How could I forget? He’d traced his long-standing depression to his time as a supply officer for a World War II combat hospital. The war, he’d said, had soured him on the idea that anything good could come from humans and left him feeling unsafe and alone.

“I remember.”

“There’s something I left out,” he says. “Something I can’t explain.” He goes on to describe one horrific, ice-cold autumn day: Casualties were coming in nonstop. He and others scrambled to transport blood-soaked men on stretchers from rail cars to triage, where those with a chance were separated from those who were goners.

“I’d been hustling all day. By the time the last train arrived, my back felt broken, and my hands were numb from the cold.”

He grimaces and swallows hard.

“What happened when the last train got there?” I ask softly.

“We were hauling one guy, and my grip on the stretcher slipped.” Tears roll down his face. “When he hit the ground, his intestines oozed out. Steam rose up from them as he died.”

Evan rubs his hands as though they were still cold.

“Later that night I was on my cot crying. Couldn’t stop crying about that poor guy, and all the others I’d seen die. My cot was creaking, I was shaking so hard. I even started getting scared that I was going insane with the pain.”

I nod, waiting for him to continue.

“Then I looked up,” he says. “Saw a guy sitting on the end of my cot. He was wearing a World War I uniform, with one of those funny helmets. He was covered in light, like he was glowing in the dark.”

“What was he doing?” I ask.

Evan starts crying and laughing at the same time. “He was looking at me with love. I could feel it. I’d never felt that kind of love before.”

“What was it like to feel that kind of love?”

“I can’t put it in words.” He pauses. “I guess I just felt like I was worth something, like all the pain and cruelty wasn’t what was real.”

“What was real?”

“Knowing that no matter how screwed-up and cruel the world looks, on some level, somehow, we are all loved. We are all connected.”

This turned out to be the first of several paranormal visits. Each time the specter arrived, he’d wordlessly express love and leave Evan with a sense of peace and calm.

“After the war, the visits stopped,” he says. “Years later, I was cleaning out Mom’s stuff after she died, and I found an old photograph. It was the same guy. I looked on the back, and Mom had written the words ‘Uncle Calvin, killed during World War I, 1918.’ ”

We talk some more, then I ask, “What does this have to do with your being in a better mood?”

“He’s back,” he whispers, staring out the window. “Saw him last night on the foot of my bed. He spoke this time.”

“What’d he say?”

“He told me he was here with me. He’s going to help me over the hill when it’s time to go.”

As I’m formulating more questions, Evan surprises me by asking one of his own.

“You ever have something strange happen? Something that tells you that no matter how bad it looks, you’re connected with something bigger, and it’s going to be okay?”

A memory flashes into my mind. It was 35 years ago. It was after midnight, and I was asleep in a graduate-student apartment at Syracuse University. A siren’s blare woke me, so loud it sounded like it was inside the room. Adrenaline pumping, heart pounding like a hammer, I sat up and wondered what had happened. Was it a dream?

From outside, I distinctly heard what sounded like a two-man stretcher crew talking.

“Bring it here quick,” one guy told the other. I heard a gurney being rolled across asphalt.

I went to the window and pulled back the curtain, certain there was trouble outside.

The night was silent. Nothing was stirring in the parking lot. No one was there.

Just before daybreak, Dad called to tell me that just a few hours earlier, my uncle Eddie had been killed in an automobile collision.

That was a tough day. As night fell once more, questions filled my head: Why did this happen? What was he experiencing when it ended? Was he scared?

On the kitchen table sat a beat-up radio; some kind of malfunction occasionally caused it to turn off or on for no apparent reason. As my questions swirled, the radio turned on, and I heard the opening chords of the Beatles’ song “Let It Be.”

Not being a fan, I’d never listened closely to the song before — but this time, I did. The music and words filled me with an almost otherworldly sense of peace and comfort. The song ended. Shortly after, the radio cut off.

For years, I tried to explain away those events. It must have been a dream, I told myself. Or some kind of fabricated “memory” to fool myself into thinking that uncle Eddie and I were connected in that moment. As for the radio, it was nothing but a random coincidence. Any other conclusion is just wishful thinking.

Inside, though, a part of me knew it was real.

After nearly 30 years as a hospice social worker, I’m certain of it. And I have patients like Evan to thank: dying patients who have convinced me that the world we inhabit is lovingly mysterious and eager to support us, especially during times of disorientation and crisis. It even sends messages of love and reassurance now and then when we’re in pain.

I return to the present. Evan is looking at me, waiting for an answer. I feel grateful that he’s pulled up these memories. Outside, a flock of crows takes off in unison from the branches of an ancient oak.

“Yeah,” I say with a nod. “I guess I have.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!