From ancient times, different peoples living on Russian territory practiced a wide variety of burial rites. There were the Slavic kurgans, the underground house tombs of Altai, the above-the-ground burials of Siberian peoples, and many more.

When Christianity came to the Russian lands in the 10th-11th centuries, it meant changing or outright erasing the Pagan traditions previously active among the many different peoples that inhabited the territory of modern Russia. With the development of the Russian state, Christian Russians conquered and subdued the lands to the East – the Urals, and then Siberia.

Christianization of the newly conquered territories was an inseparable part of the process of conquest. And Christian burial rites slowly replaced indigenous ones. Still, archaeological and historical sources managed to preserve a wealth of information about how the various peoples of Russia buried their dead before Christian burial rituals started prevailing. Let’s take a brief look at the variety of these indigenous burial rites.

Above-the-ground burials

It appears that above-the-ground burials were practiced among the peoples of Russia long before Christianity. Russian folk tales have preserved echoing mentions of such rituals. Baba Yaga, the evil witch, lives in a hut standing on chicken legs deep in the forest. This hut has no windows or doors, and Baba Yaga has a “bone leg” – apparently, here the tales describe an above-the-ground burial, a carcass interred into a wooden casket, placed on wooden pegs.

The Mokshas, a Mordvinian ethnic group living in Central Russia, are known to have practiced burying their shamans this way. Later, during Russia’s christianization, most such gravesites were destroyed, but the burial practice itself remained in use in Siberia for centuries to come, as the Russian state was slow in conquering and controlling Siberia.

The Nenets people are the largest ethnic group of Siberia. In their view of the afterlife, a human’s soul after death continues the way of life it led during its lifetime. So, it was very important for the Nenets people to bury their dead fast. On the next day after death, the body was transported to the graveyard site using deer.

The Nenets graveyards were usually located on hilltops. After the body was brought there, it was placed inside a wooden casket along with tools, weapons and other things the deceased might need in the afterlife – all these things were bent or broken beforehand so that they could be used in the afterworld. The deer that transported the body were sacrificed at the place of the burial. But it was not a burial in the strict sense, because the Nenets didn’t bury their dead – the frozen northern land did not allow digging deep holes, so the casket was covered with brushwood and left on the site. The villagers didn’t maintain the graves either – the bodies were left to decompose naturally. If infants or children died, their bodies were hanged in sacks on the tree branches, a kind of ‘sky burial.’

The Buryat people, who live in the Baikal region and nearby, also practiced above-the-ground burials. They dressed their dead relatives in their finest clothes, laid them on the ground with weapons, tools and elements of horse harness, and then covered them with earth, stones or brushwood. They tried to place the body where wild animals are found, so that the soul could quickly go to its ancestors.

The Altai house-tombs

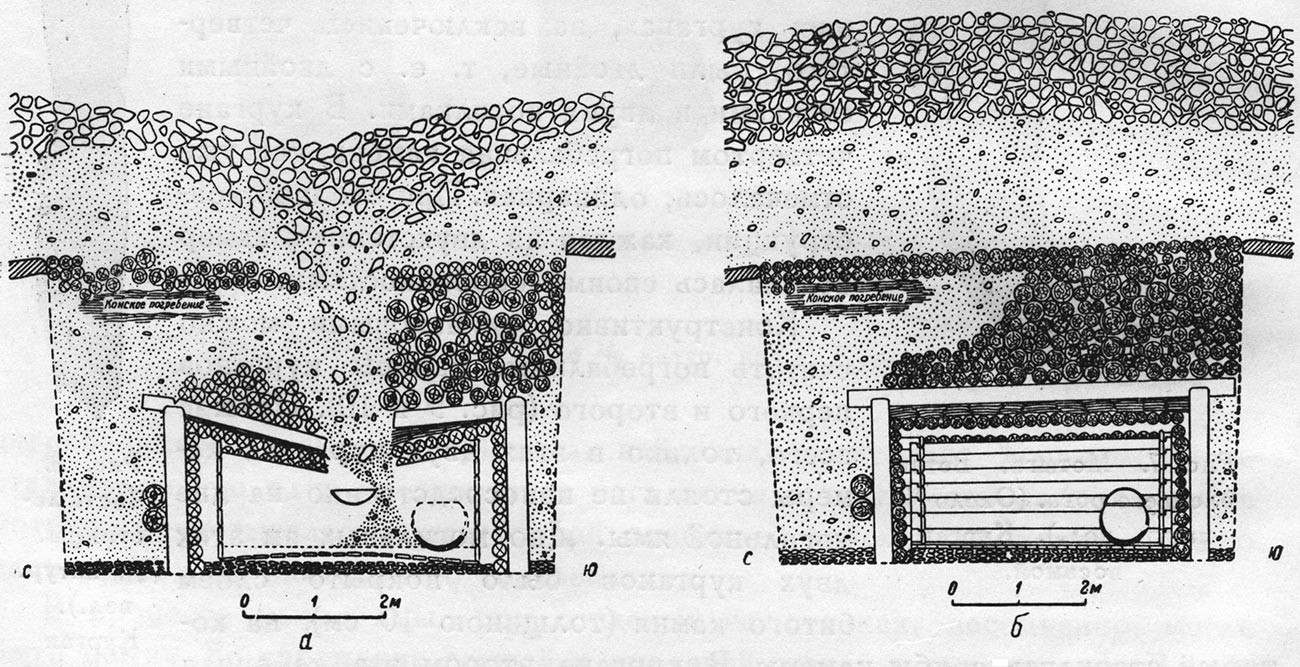

In the 1990s at the Ukok plateau in the Altai Republic of Russia, vast burial grounds were discovered by Russian archaeologists. The barrow-type burials, or kurgans, as they are called in Russia, belong to so-called Pazyryk culture – the ancient Scythian society that inhabited the territory in the 5th-4th centuries B.C.

The most notable find was the so-called ‘Siberian Ice Maiden’, a tattooed shaman woman buried with six sacrificed horses and a lot of treasures. But it was just one of many burials where the body was astonishingly well preserved because of the waters that inundated the burial sites and then froze, preserving the graves’ contents embedded in ice.

The Pazyryk kurgans were indeed houses made for the dead. A full log cabin was placed underground, with a separate room inside for housing the body. Fully dressed, it was placed in a log casket, and around the casket, the belongings needed for the afterlife were placed – horses, harnesses, carpets, weapons, and even carts and chariots. Of course, only noble and wealthy Pazyryk were buried in such an expensive and complicated kind of way.

Slavic kurgans

A kurgan is a type of tumulus (burial mound) constructed over a grave. Mostly, kurgans were constructed for the wealthy and noble people – warriors, princes and so on, and were usually just small steep hills formed over the gravesite. Kurgans spread into much of Central Asia and Europe during the 3rd millennium BC.

There are still a lot of Slavic kurgans in Central Russia, but all of them are now just kurgan sites – during the long history of their existence, all visible kurgans have been looted in search of treasures. Still, we know how kurgan burials were performed.

A kurgan could be constructed quickly by bringing a mass of earth together and surrounding the foundation with stones or wooden logs. The body of the deceased was dressed in the best clothes, and a funeral feast was held, along with the cremation of the body. The remains were then interred inside the kurgan and covered with earth and stones. Along with the body, weapons, armor, household utensils, money, and other items could be interred. No tombstones or other signs were placed atop Slavic kurgans.

Dolmens

Dolmens, ancient megalithic tombs, are so old that we don’t even know the cultures they originated from. Dolmens date back to 3000-2000 B.C. In Russia, most are located in the North Caucasus.

Created from sandstone and limestone, dolmen tombs usually have four walls and a roof. A hole is cut in one of the walls, most likely for placing the body inside the closed chamber. Stone stoppers would then be used for closing these holes. Dolmens could have been covered with earth kurgans, also.

No traces of kurgans or human remains inside the dolmens were found, because of the very old age of the structures. But we can be sure they were used as tombs: they are astronomically oriented, with some clearly used as family crypts, and others as sanctuaries.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

/https://public-media.si-cdn.com/filer/55/17/551755a5-bdfa-4bf1-aa5d-1696222770df/mtoto_artwork_by_ffueyo_v2_web.jpg)