— The battle over how science defines the end of life

The concept of brain death is facing its greatest challenge in the United States in decades.

Ideological differences threaten to muddy the definition of death in the United States — with potentially negative consequences for clinicians and people awaiting organ transplants.

By Max Kozlov

Dead in California but alive in New Jersey: that was the status of 13-year-old Jahi McMath after physicians in Oakland, California, declared her brain dead in 2013, after complications from a tonsillectomy. Unhappy with the care that their daughter received and unwilling to remove life support, McMath’s family moved with her to New Jersey, where the law allowed them to lodge a religious objection to the declaration of brain death and keep McMath connected to life-support systems for another four and a half years.

Prompted by such legal discrepancies and a growing number of lawsuits around the United States, a group of neurologists, physicians, lawyers and bioethicists is attempting to harmonize state laws surrounding the determination of death. They say that imprecise language in existing laws — as well as research done since the laws were passed — threatens to undermine public confidence in how death is defined worldwide.

“It doesn’t really make a lot of sense,” says Ariane Lewis, a neurocritical care clinician at NYU Langone Health in New York City. “Death is something that should be a set, finite thing. It shouldn’t be something that’s left up to interpretation.”

Since 2021, a committee in the Uniform Law Commission (ULC), a non-profit organization in Chicago, Illinois, that drafts model legislation for states to adopt, has been revising its recommendation for the legal determination of death. The drafting committee hopes to clarify the definition of brain death, determine whether consent is required to test for it, specify how to handle family objections and provide guidance on how to incorporate future changes to medical standards. The broader membership of the ULC will offer feedback on the first draft of the revised law at a meeting on 26 July. After members vote on it, the text could be ready for state legislatures to consider by the middle of next year.

But as the ULC revision process has progressed, clinicians who were once eager to address these issues have become increasingly worried.

Fuelling their fears is a rising tide of political polarization and mistrust of scientific expertise. Some clinicians following the ULC discussions say that the idea of brain death itself is facing its greatest challenge since its conception in the 1960s. The outcome could have serious implications for intensive care units (ICUs) across the United States and might affect the availability of vital organs for transplant. And although few expect the ULC’s recommendations to erase the idea of brain death, some observers fear that the doubts and narratives sown throughout the process could have a lasting effect on state laws and on public perception.

“I thought this would be an upgrade, and it’s completely fallen apart from that perspective,” says Robert Truog, a bioethicist and paediatrician at Harvard Medical School in Boston, Massachusetts, who is not a voting member of the ULC committee, but has watched its progress closely. “As soon as we talk about the deeper issues, the profound disagreement of some members of the committee become apparent, and you reach a standstill.”

Redefining death

Current legal definitions around the world generally allow for two types of death: when heart and respiratory function stop irreversibly, or when crucial functions of the brain are lost. Historically, these two have been closely entwined: stop the heart, and the brain is dead in minutes. Stop the entire brain functioning, and the heart stops beating. But medical advances in the 1950s, such as modern ventilators, meant that the two types of death could be separated.

Such technologies, along with improved methods of measuring brain function, prompted the formation of a committee at Harvard University in Cambridge, Massachusetts, in 1968. The members developed a definition of irreversible coma or brain death that was controversial at the time.

In 1981, prompted by a presidential commission on the topic, the ULC codified this form of death into a model law called the Uniform Determination of Death Act (UDDA), stating that a person can be considered dead when there is an irreversible cessation of circulatory and respiratory function or of all functions of the entire brain, including the brainstem. The Harvard committee and the UDDA proved influential: most countries in the world followed suit with their own laws adopting brain death.

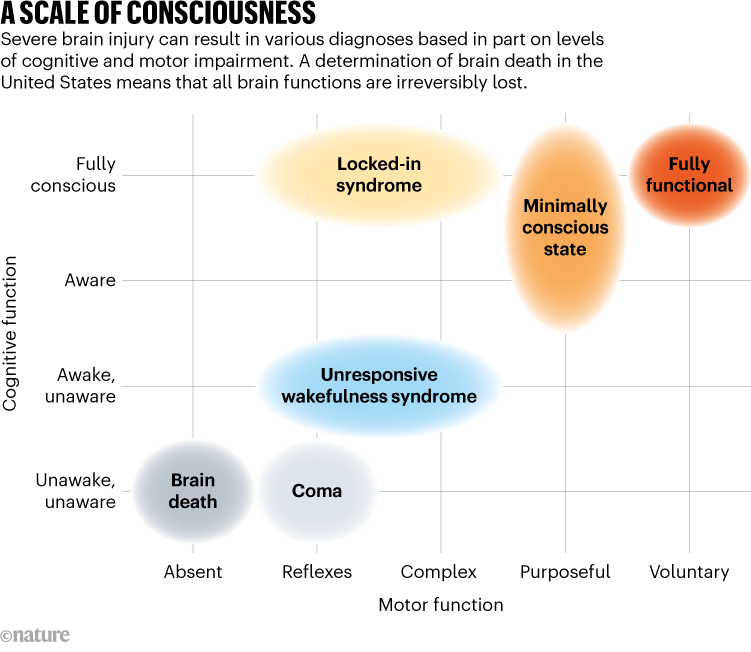

People who are in a coma, or who have unresponsive wakefulness syndrome, or locked-in syndrome are not brain dead. Not all functions of their brains have stopped, and some might be able to breathe without the assistance of a ventilator, show signs of wakefulness or have intact reflexes (see ‘A scale of consciousness’).

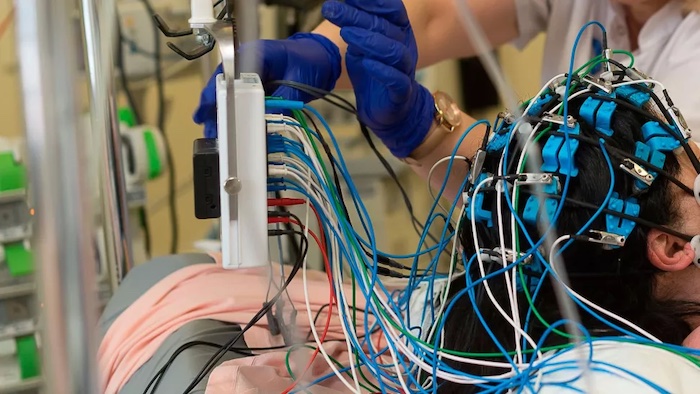

Today, although brain death makes up just 2% of adult deaths and 5% of childhood deaths in hospitals in the United States, it tends to garner outsized attention from the media and in the law. Erin Paquette, a paediatrician and bioethicist at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois, says that’s because the physical appearance of a person who is brain dead often doesn’t line up with people’s concept of death. Hooked up to a ventilator, a person who is brain dead might look like any other individual in an ICU.

This can make it difficult for clinicians to communicate with family members about brain death, especially when the law lags behind scientific understanding. This happened in McMath’s case. Although she never definitively regained consciousness or the ability to breathe on her own, she began puberty and had her first menstrual period — a sign that a small region of her brain called the anterior hypothalamus, which helps to control the body’s hormones, might have been active.

This realization prompted her mother to sue the state of California in a bid to erase the death certificate there because not “all functions of the entire brain” had ceased as the UDDA dictates. Using a strict interpretation of the law, McMath’s mother might have been right, says James Bernat, a neurologist at the Dartmouth Geisel School of Medicine in Hanover, New Hampshire, even though it wasn’t a sign that the girl would recover. The anterior hypothalamus, Bernat says, receives blood through a different supply from the rest of the brain, so some function might be preserved in a small subset of people who have been declared brain dead. (McMath’s heart stopped in June 2018, at which point she was issued a second death certificate; her mother withdrew the lawsuit shortly afterwards.)

Language tweaks

Clinicians have called for changes to the language of the UDDA, hoping to clarify which brain areas are relevant to recovery. Other countries, such as the United Kingdom and India, define brain death much more narrowly than the United States, focusing not on the entire brain, but on the brain stem, which is necessary for essential functions such as breathing, swallowing and maintaining a heartbeat. The United Kingdom goes one step further by not separating the ways that death happens: all deaths happen when brainstem function is lost.

Truog supports this simplified system, which Canada adopted in May. But Bernat says it’s unlikely that the United States will adopt this standard: “If the ULC is going to do anything to the UDDA, they want to just tweak it,” he says. Nevertheless, he hopes that the revised law will address how to interpret residual activity in areas of the brain that are not linked to consciousness or breathing.

Other language changes are more subtle. Some clinicians have been calling to amend the law so that it refers to a ‘permanent’ loss of brain and heart function instead of an ‘irreversible’ one. The argument is that current tests for death do not evaluate reversibility, but rather permanence. Irreversibility, clinicians say, is a much higher standard to meet, and would require them to wait for hours to prove that they cannot restart heart or brain function. And even if it were possible to restore some functionality, some have said it might not be wise or even ethical to do so.

The need to address the language about irreversibility has been made more urgent thanks to research by Nenad Sestan, a neuroscientist at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. He and his colleagues pumped a blood substitute through the bodies of pigs and restored cellular function in some organs1, including the brain2, hours after the animals were slaughtered. They were careful to note that although cells might be metabolically active, this does not translate to organ function. “We might one day be able to reverse things we used to say were irreversible, and ultimately what we care about is permanence,” says Alex Capron, a medical ethicist and specialist in health policy at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, who helped to direct national efforts to define death in the 1980s.

These language discrepancies mean that guidelines put out by organizations such as the American Academy of Neurology (AAN), in Minneapolis, Minnesota, outlining what physicians should test for when declaring brain death don’t line up with the UDDA.

Individual hospitals, too, have their own determination-of-death policies and procedures that might differ from those put out by the AAN. Currently, the UDDA states that physicians ought to use “accepted medical guidelines” as the basis of their determination, but that leaves room for them to use different medical organizations’ guidelines, and ones that are outdated.

In 2016, David Greer, a neurologist at Boston Medical Center, and his colleagues were surprised to find substantial differences when they analysed nearly 500 hospitals’ policies to see whether they adhered to the AAN’s guidelines3. They found that most clinics did not require someone with neurology experience to determine brain death, and more than one-quarter didn’t require physicians to test for conditions that can mimic brain death, such as abnormally low blood pressure or hypothermia.

New AAN guidelines are coming later this year, says Greer, who co-authored them. The revision will standardize death determination between adults and children to make the concept easier for people to understand, he says. Greer and others are calling for the UDDA to specify which medical guidelines to rely on and a process by which states can incorporate newer standards into practice.

Added tensions

But some are afraid that the time is not right to update the UDDA. Lainie Ross, a paediatrician and bioethicist at the University of Rochester in New York, says that when she heard this process was opening up, she felt uneasy. “It’s not that I think what we have is perfect,” she says, “but sometimes, perfect is the enemy of the good.”

Ross says her fears have been borne out — and many other medical professionals who spoke to Nature agree that the ULC discussions so far have not been as productive as they would have liked.

One concern is a lack of scientific expertise. The ULC committee that will ultimately decide on the final text of the revised UDDA consists of 15 voting members, all of whom are attorneys, and none of whom has direct experience treating people with severe brain injury.

One of the commissioners is James Bopp Jr, who serves as the general counsel for the anti-abortion organization the National Right to Life Committee in Washington DC. He says that he publicly supported the UDDA in the 1980s, but has changed his mind in the past few years and no longer thinks that brain death constitutes biological death. He now argues that even if a person has no chance of recovery, they still have rights.

So far, Bopp’s efforts to remove brain death from the UDDA have not succeeded. But although the concept of brain death will probably remain in the United States, the ULC might approve bracketed text, which serves as an optional recommendation for state legislatures as they consider revising their laws. This bracketed text could include a clause similar to New Jersey’s current law, allowing people to object to a diagnosis of brain death for reasons such as religious beliefs.

Many agree that it’s important to include language to handle objections and accommodations, but allowing for such opt-out clauses in the UDDA has split researchers. Truog is in favour of them, adding that they are the only sure-fire way to stop the deluge of lawsuits that threatens to undermine public acceptance of brain death. But Ross says that consistency is paramount, so she would prefer that either no states have an opt-out clause, or every state has one — to avoid the situation in which someone is considered alive in one state but dead in another.

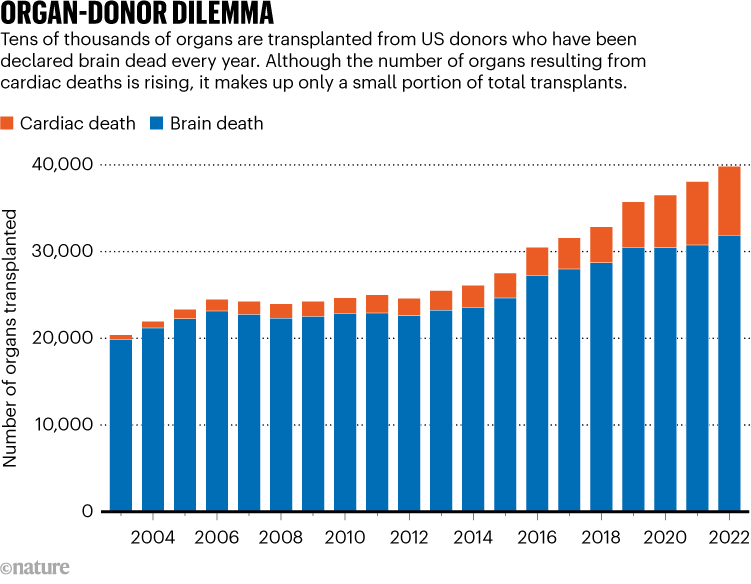

To add to the tension, people who are brain dead represent most deceased organ donors in the United States (see ‘Organ-donor dilemma’), meaning that any changes to how death is determined will also have knock-on effects on the organ waiting list — which currently stands at more than 100,000 people. The worry is that with more people refusing to accept a determination of brain death, the waiting list could grow substantially, and ICUs could be filled with people who will never recover.

Truog says that New Jersey has had its opt-out clause for years, and it has neither massive organ shortages nor ICUs filled with people who are brain dead. But Capron cautions that expanding opt-outs for religious reasons to many states would be venturing into uncharted territory. And signalling that brain death isn’t universally accepted could “have an effect on people who would not have gone into it having any doubts”, he says. The logistics of organ transplantation also become sticky in this scenario: organ-transplant registries have become more national. Higher opt-out rates could pose an obstacle if one state’s population is providing fewer organs to the registry but still requires the same number, Ross says.

Exploring other options

The outcome of the UDDA revision process is still largely unknown. The ULC could recommend leaving the 1981 UDDA intact. In that scenario, individual state legislatures could still vote to revise their laws in any way that they see fit, but it would be without an explicit recommendation from the ULC. If drafting continues as planned, the full ULC will vote on the revised UDDA at its summer 2024 meeting.

Beyond revising the UDDA, there are other, more systemic, ways to build public trust in the concept of brain death, Paquette says. One example is more uniform and robust medical training: because brain-death determinations are relatively infrequent, many neurology residents in the United States finish their training without witnessing a single brain-death examination4. This can result in less uniformity between clinicians and poor communication with the family or carers of a person with a devastating brain injury. Students need more practice in communicating diagnoses and potential outcomes with the family or carers of a person with a devastating brain injury, Paquette says.

“It’s helpful to outline what the death based on neurologic criteria process will look like,” she says. “And it’s important to acknowledge that what someone is seeing might not match up with their notion of death.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!