By Kathy Aney

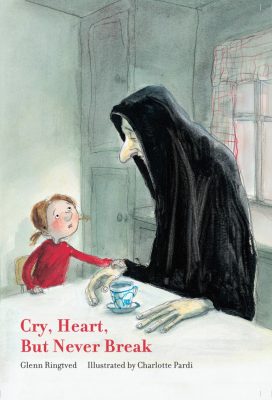

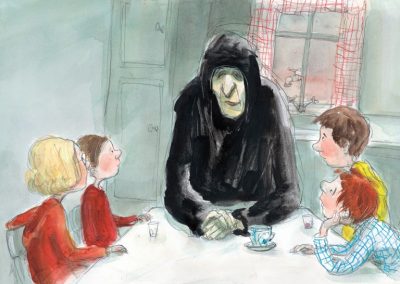

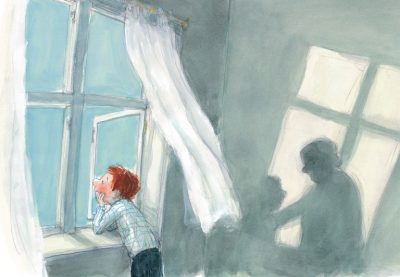

Children don’t experience grief quite the same way as adults.

“Children pop in and out of pain and sadness,” said children’s counselor and author Donna Schuurman. “Adults tend to be more steeped in their grief — they don’t bounce in and out as much and often sleepwalk through their grief.”

This is Children’s Grief Awareness Month, a time to consider the needs of these sometimes forgotten mourners.

Schuurman, author of the book “Never the Same: Coming to Terms with the Death of a Parent,” knows a little something about children’s grief. She has a 30-year stint with the Dougy Center in Portland, which provides a haven for grieving children and their families. She and other Dougy Center staffers have also assisted after large-scale tragedies such as the Oklahoma City bombing, 9/11 attacks and the 2011 earthquake and tsunami in Japan.

When someone dies, children grieve. Sometimes adults make the process harder.

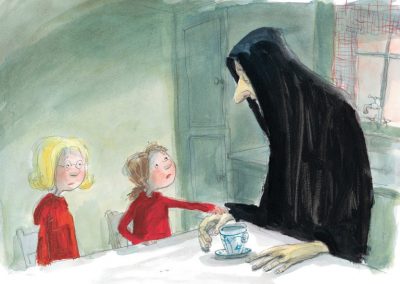

“There are a lot of things people do to make it worse, such as not allowing kids to have their feelings, whatever they are,” Schuurman said. “We have a tendency to want to cheer people up.”

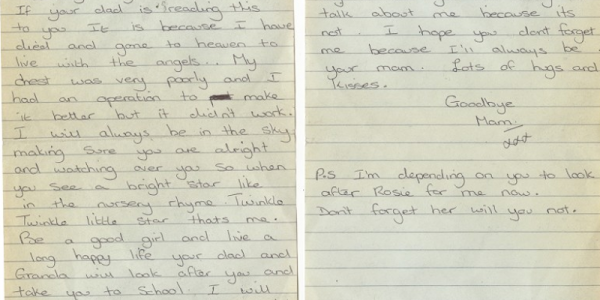

Talking about the person who died is a good thing, instead of avoiding the subject. Sharing memories helps kids heal.

“They are trying to hold on to precious threads,” she said. “Acknowledge the person with “There’s nothing I can do to bring your dad back, but I want you to know I care” or “Can I tell you a story about your dad?”

After a death, children worry about their other family members dying, too.

“Anyone could die any moment,” she said. “There is heightened anxiety.”

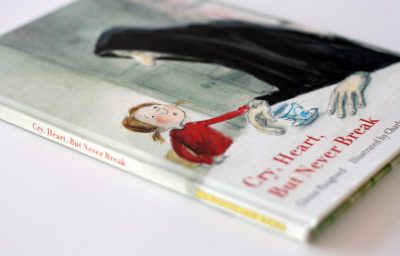

Children sometimes don’t have the words and experience to understand death the same as would an adult. In one Dougy Center video, a three-year-old named Myia described losing her mommy.

“I wanted to sing ABCs with my mom and she stopped singing,” Myia said. “Her body stopped singing.”

“Then what happened?” a Dougy Center staffer asked from off camera.

“She died and then I was crying,” Myia said. “It was not good. I had a bad feeling.”

The little girl’s brown eyes radiated deep sadness, more than any child should have to bear.

As with adults, a child may take a long while to grieve a loss. That’s okay, Schuurman said.

“In our society, we want quick fixes. We want to get through it,” she said. “You can’t rush grief. It’s not quick. It takes digestion time.”

Basically, Schuurman said, there’s no map for the grief journey and sometimes the process is not a linear one.

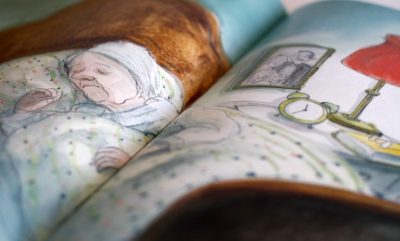

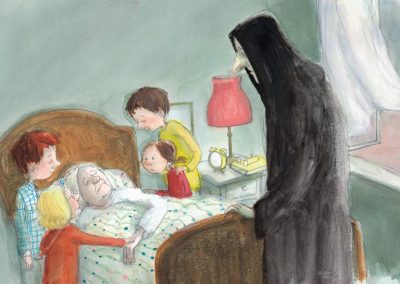

Children need to recalibrate their lives after the death of a parent, sibling or other loved one. Sometimes there is guilt. Relationships are complicated, that way. A sibling, for example, might have been someone the child both loved and hated, depending on the moment.

If a death came with a lot of physical trauma, a parent might wonder how much to tell a child about the person’s final moments. Schuurman urged candor, as much as the child can handle.

“It’s best to answer their questions honestly, but don’t tell them more than they’re asking or they are open to,” she advised.

When a child asks whether the person died instantly or whether he or she suffered, it’s tough.

“You want to say no when the reality is they were moaning for an hour,” she said. “I might say, ‘From what I understood of the hospital report, he didn’t die instantly. I don’t really know, but the body protects us from horrible pain by going unconscious.’”

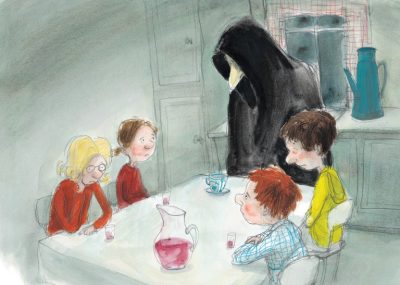

Processing grief is easier when the child can spend time with other children who have suffered loss.

“Until you experience death in your own life, it’s hard to understand,” she said. “So you come to be with others who get it.”

Complete Article HERE!