[P]ets are part of the family, so it makes sense that losing one is tough on everyone, including our children. A pet’s death may be the first time they’ve ever experienced a real loss, and as a parent, it can be difficult to know how to start a conversation about life, death, and grieving in a way they can understand, but that won’t heighten their sadness.

Last week, we put our 12-year-old dog to sleep five weeks after he was diagnosed with lymphoma. It was a brief but rapidly debilitating illness, and I wondered if my kids would understand that a dog who was quite healthy only two months ago was now gone. Surprisingly, they took it much better than I did. My 3-year-old gave me a hug, then told me, “I don’t know why you’re crying, Mom. Gus was sick, and now he’s in heaven with grandma’s dog. He’s not sad he died. He’s still happy.”

After briefly wondering if my child was a pet psychic, I realized that his logic was pretty sound. While my son would miss our dog, he knew our pup had been suffering, and he was prepared for the death. He had processed the loss faster and more easily than I did precisely because he was a kid. If you’re dealing with the loss of a family pet, here’s how to help your children process their feelings.

- Make sure your child understands what death means. Gently make sure that your child understands that their pet’s death means the animal will never be physically present again. Don’t be alarmed if it takes awhile — even years depending on their age — for your child to understand that means that your pet can no longer breathe, feel, or ever be alive again. If the death was sudden or unexpected, explaining why or how your pet died might be important to help your child understand the permanence of the loss. Of course, consider your child’s age and ability to understand and only give them developmentally appropriate information.

- Be honest. Telling your child about the death openly and truthfully lets your child know that it’s not bad to talk about death or sad feelings, an important lesson as they will have to process many other losses throughout their lives.

- Follow your child’s lead. Sometimes children are better than adults at accepting loss, especially when they’ve known for some time that their pet had a limited life span or was ill. Don’t attempt to make your child’s grief mirror your own, but do validate any emotions that come up as your child goes through the mourning process, and be ready to talk when they have questions. Age-appropriate books like Sally Goes to Heaven and I’ll Always Love You can also help with communication.

- Don’t be surprised if your child grieves in doses. Children often spend a little time grieving, then return to playing or another distraction. This normal, necessary behavior prevents them from becoming overwhelmed and makes the early days of grief more bearable for them.

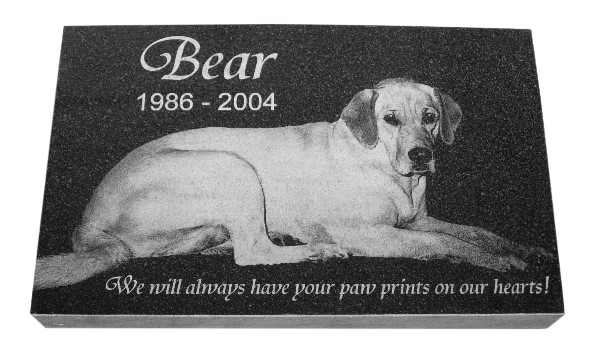

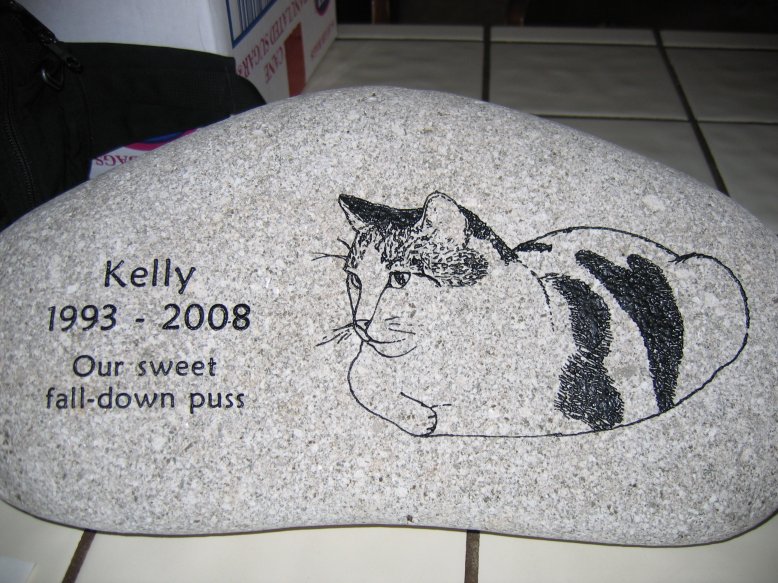

- Say a formal goodbye. Consider having a small memorial service where you can all say goodbye, discuss favorite memories, and thank your pet for being part of the family, even if the service is just in your backyard or around the kitchen table.

- Find a way to memorialize your pet appropriately. We often don’t realize how constant our pets were in our lives until they’re gone. By making a photo album, turning a collar into a Christmas ornament, or commissioning personalized art work through Etsy, your whole family will have a positive remembrance of your beloved pet for a lifetime.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!