– An expert guide to talking to kids about death during Covid

By Robyn Silverman

My daughter’s questions started after a family friend got sick with Covid-19.

“If people are sick, they can just give them medicine so they get better, right?” my daughter asked with the hopeful perspective of an 11-year-old. “They can just go to the hospital so the doctors and nurses can help them?”

The questions stemmed from a positive update my husband gave about his martial arts buddy, John R. Cruz, a first responder being treated at Holy Name Medical Center in Teaneck, New Jersey.

He’s one of the lucky ones.

Not everyone is as fortunate. We’ve already surpassed 124,000 Covid-related deaths in the United States and nearly half a million dead worldwide.

For adults, these numbers are shocking. For children, they are unfathomable. Some can’t even conceptualize the notion of a single death.

It’s natural for parents to want to protect children from the feelings of worry and distress we are experiencing during this pandemic, but decades of research underscores that being honest with children is the best way to mitigate feelings of anxiety and confusion during uncertain times.

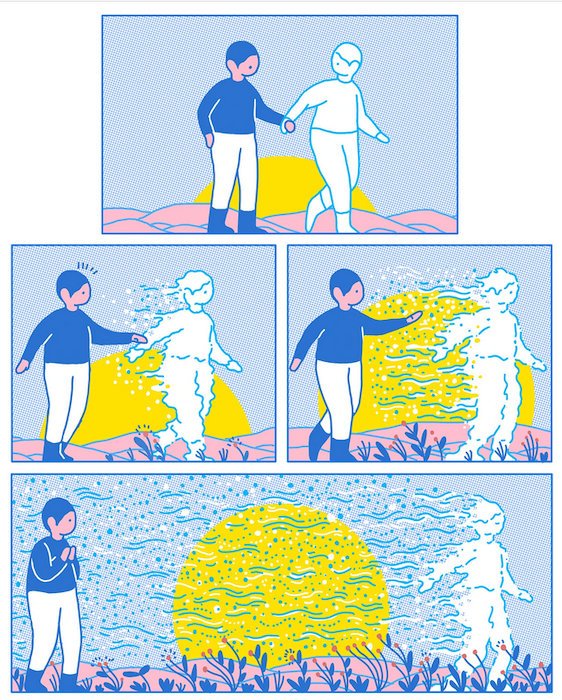

Even young kids are aware of the changes in the emotional states of adults and will notice the absence of regular caregivers, including grandparents.

So how do we talk to kids about death and dying during the coronavirus crisis? These are tough talks, no doubt about it. Here are six guiding principles, with sample prompts and scripts, to keep in mind.

Assess what’s age-appropriate

While parents should always be honest about death, the information you divulge may differ in amount and depth depending on the developmental age of your child.

How do you know where your child falls? It’s a best practice to follow your children’s lead and answer their questions without volunteering additional details that may overwhelm them. If you don’t know the answer, it’s OK to admit it.

Children between the ages of 4 and 7 years old believe that death is temporary and reversible, punctuated by the fact that their favorite cartoon characters can meet their doom and then come back the next day for another episode.

Even after you explain that “all living things die” and “death is the end of life,” it’s normal for young children to ask, “When can that person can come back?” Be prepared to remind them, kindly and calmly, that “once a body stops working it can’t be fixed” and “once someone dies, that person can’t return.”

Older children grow out of this “magical thinking” as they enter tweenhood, questioning the meaning of death during adolescence, while often seeing themselves as invulnerable to it. They may want to talk with you about why someone has died and need guidance about which resources they can trust for valid information about coronavirus and Covid-related deaths.

Ask your children, whatever their age: “What have you heard about the coronavirus and how someone might get it? What do you know about what happens when someone gets sick from it?” Clarify the difference between the virus and the disease and explain who is at the highest risk for becoming severely ill from Covid-19.

Prepare yourself

A conversation about death, especially when you are reporting on a family member or close friend, is especially difficult. You don’t want to just blurt out the news without carefully considering your words. Give yourself some time to gather your thoughts and take a couple of deep breaths.

Ask yourself: Do I want another supportive adult with me while I deliver this news? Where in my home would be best to discuss this with my child? Should my child have a special toy or comforting blanket with him or her when we have this conversation?

Even though it’s best to discuss what happened with your child before someone else tells them, taking a few minutes to calm yourself down and be present is important for you and for them.

Explain what happened

If someone in your children’s world does pass away from Covid-19, be sure to tell them honestly, kindly, clearly and simply. Experts agree that parents should avoid euphemisms such as “went to sleep,” “we lost her” or “went to a better place” to avoid confusion.

Instead, you might say; “Sweetheart, remember Grandpa got very sick and has been in the hospital for the last few weeks? His lungs stopped working and couldn’t help Grandpa breathe anymore. The nurses and doctors worked so hard to try to make Grandpa’s body healthy again but they couldn’t make Grandpa better. We are so sad and sorry. Grandpa died today.”

Then pause and listen. You may need to repeat your words a second time as distress can make it difficult to digest information.

Give room for the ups and downs of grief

In a time of suffering, it can be difficult to know what to say. Honesty about your own emotions gives children permission to be open about their own confusion, sadness, anger and fear.

You might admit: “This is all so hard to take in, isn’t it? I am feeling sad, and I’m crying because I miss Grandpa.”

Don’t be surprised if some of your child’s feelings come out all at once, while others may peek out days and weeks after the death of a loved one. Be ready for the unexpected and know that, when children grieve, they may be crying one minute and playing the next. This is normal.

“Grief is not a linear process,” said Joe Primo, CEO of Good Grief, in an interview on my podcast, “How to Talk to Kids about Anything.”

Good Grief is a New Jersey-based nonprofit organization that provides healthy-coping skills to children grieving the loss of a family member.

“Grief is like a roller coaster. It’s up, down, all around. For kids and adults alike, every single day is different. And as the grieving person, you have no idea how your day is going to unfold.”

Answer questions

Many children will ask for more information and want to know why their loved ones didn’t survive. Reiterate that your loved one had Covid-19 and the medical team worked very hard but the disease made it so the body could no longer work. You might tell your child about complications such as asthma that made it difficult to breathe even before the coronavirus.

It is also normal for your child to ask if you or others in their life will get sick or die of Covid-19 so be clear about the precautions your family is taking in order to stave off the illness.

“We are doing everything we can to stay healthy. We are washing our hands with soap and water, keeping our home very clean and staying away from others to keep from getting the virus,” you might say.

“We are also wearing masks and gloves when we are at the store to get groceries. And don’t forget, we are continuing to eat nutritious food, exercise and get good rest to keep ourselves strong.”

Provide ways to commemorate and honor

Given that social distancing is making it increasingly difficult, if not impossible, to grieve alongside loved ones as we typically do when someone dies, it’s imperative that we find a way to allow children to say goodbye and remember. Studies have repeatedly found that when children are part of funerals and celebration of life events, they fare better.

“Funerals are about mourning,” Primo noted, “and mourning is a core component of a child adapting to their new norm, expressing their grief, and getting support from their community.” Without these traditional markers, find other ways to honor your loved one.

For example, have a small home-based ceremony and commemorate the person’s life by planting a tree, doing an art project, reading a poem, eulogizing and saying goodbye. You can also collect letters, video tributes and memories from others and share them with your children. Many have used Zoom to remember those who died. Ask your children, “How would you like to honor and remember _______?”

This conversation may be one of the toughest you will have with your kids, and one that, given the numbers, will be part of many families’ reality as we cope with incredible loss from the coronavirus. It’s stressful for everyone involved — for your children and for you, too.

Continue to reach out for the support you need so you and your children can be cared for during this difficult time. Even while we must be socially distant, no one should have to grieve alone.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!