Thailand’s bereaved pet owners who take their dearly departed dogs to Wat Krathum Suea Pla, a temple on the outskirts of Bangkok, where ceremonies and rituals are believed to speed the animals’ reincarnation and boost their karma

By

The Suwans, a family of five, have brought the earthly remains of their dead pet to Wat Krathum Suea Pla, a Buddhist temple on the outskirts of Bangkok. They’ve come to administer the last rites to their late canine companion to boost his karmic prospects.

“Beckham was like one of my own children to me,” says Saythan Suwan, 43, a mother of two. She rescued the dog from the streets in 2004 and named him after English footballer David Beckham, who is hugely popular in Thailand.

The stray pup became a loyal member of the Suwan household. He guarded the premises, played with the children and shared a bed with grandma, who died recently at age 84. When Beckham took his last breath, the Suwans bathed his body, sat in vigil, and the following morning took him to the Buddhist sanctuary to be cremated.

“We want to do the best for him so he can be in the best place in his next life,” explains Saythan, a saleswoman. “If Beckham is reborn, I hope he gets reborn as a member of our family again. We hope he will come back to us as a puppy.”

To help ensure this happens, the Bangkok family have paid for a private ceremony at the temple on their dead dog’s behalf.

In the predominantly Buddhist country, where age-old superstitions still hold sway, most locals believe that by performing meritorious deeds, such as giving alms to monks, they can earn valuable karmic points for deceased loved ones, thereby hastening their rebirth in an auspicious new incarnation. And for an increasing number of Thais, like the Suwans, these deceased loved ones include pets.

The Suwans are gathered mournfully in a small chapel, where Beckham lies draped in lily-white funerary shrouds on a bier among colourful garlands and bouquets of flowers. One by one they sprinkle the dead canine with marigold petals and take turns pouring scented water over him from a small decanter.

“If I’ve wronged you, please forgive me. If you’ve wronged me, I forgive you,” a funeral assistant intones on account of the dead dog, during a service with stylised rituals that closely follow those of human funerals.

Sitting cross-legged on antique wooden chairs inlaid with mother-of-pearl, four monks chant plaintively for Beckham’s benefit. In return, the family offer the monks new robes and provisions in their dog’s name.

Beckhamis then taken outside to a small crematorium custom-made for pets, where the Suwans place roses fashioned from wood shavings on his corpse in a final tribute.

“We will scatter his ashes in the [Bangkok’s] Chao Phraya River,” explains Anyamanee, one of Saythan’s daughters. “We scattered my grandmother’s ashes there. She and Beckham were always together in life,” she adds. “We want them to be together in death, too.”

Outside, another dog is waiting to receive the same treatment. Lying peacefully on a metal table is Nimbus, a 10-year-old husky. He looks as if he is asleep. The night before, he began pacing agitatedly and died soon afterwards, explain his tearful owners, a Thai-Chinese man and woman.

“He seemed to be in pain and then he passed away,” the man, who identifies himself only by his nickname, Chok (“Luck”), says between sobs. “We believe he will come back to us – maybe in another form.”

Presently it’s Boozo the poodle’s turn. He’s just died of renal failure. He is placed in a small fuchsia coffin where he’s wreathed in flowers. “He brought us so much joy and so much luck,” Payao Tang-on, 63, says. “We won the lottery because of him.”

She now wants to get the dead pet on the spiritual highway to rebirth. “If we had buried him, his body would have taken a long time to decompose,” Payao says. “This way his spirit can get into a new body faster. He may even be reborn as a person.”

According to Phrakru Soponpihankij, the temple’s abbot, only a few animal species – including elephants, horses, dogs and cats – can be directly reborn as human beings. “But usually, even loyal companion animals can’t earn enough merit on their own in this life for that, so people have to do it for them,” he adds. “Monks are intermediaries between this life and the next. They can help animals gain more merit.”

Next up for a treatment of monk-assisted extra karmic merit is Luke, a small mixed-breed dog with fluffy, off-white fur, who died of bone cancer. “He was as good a pet as you could ask for,” says his owner, a retired American executive who came with his Thai wife to bid tearful farewell to the dog. “We want to send him off to something better,” he adds. “I’m not sure I believe in the Buddhist concept of reincarnation, but you never know.”

Within three hours on this Saturday morning, four dogs and a cat are cremated in quick succession at Wat Krathum Suea Pla. On some days, says Worratap Janpinid, who operates the crematorium, as many as 20 dead pets are brought here for funeral services – mostly dogs and cats, but there have been rabbits, monkeys, birds, tortoises, goldfish and even monitor lizards.

“I’ve cremated thousands of pets,” Worratap says. A wiry man in his 20s, he is covered in magic tattoos all the way up to his shaven pate, and wears unwieldy signet rings with protective amulets on several fingers to ward off misfortune and death. “Many people who come here have good hearts,” he says.

One bereaved dog owner drove his dead companion 1,000km to the Bangkok temple from the southern Thai province of Satun for a proper pet funeral. The sanctuary lies in a warren of winding streets in an industrial area that was once marshland. It’s one of the few Buddhist temples in Thailand that assist pet owners in administering proper funerary ceremonies for their animals.

Many other temples dispose of the bodies of pets and stray animals, but they do so with little ceremony. Routinely, the carcasses of beloved pets are burned in incinerators, often without their owners’ knowledge. This practice appalled Teerawat Saehan, the proprietor of a pet grooming salon who was invited by a customer to a dog’s funeral. “It looked as if pets were treated like rubbish,” he recalls.

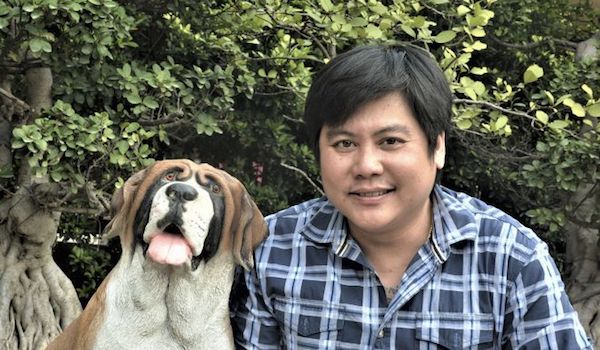

So a few years ago Teerawat set up Pet Funeral Thailand, a small company that specialises in elaborate cremation ceremonies for pets. “We started replicating human funerals for pets,” says Teerawat, 37, an amiable man who also sports magic tattoos. “People come to us because we do things properly.”

Business is booming. Each month the company hosts 300 to 400 pet funerals, which cost anywhere between 1,500 baht (US$48) and 400,000 baht. The price depends on variables such as the length of the service and the number of monks present. The most expensive pet funerals are overseen by as many as 60 monks and feature special funeral processions, including motorcades. At some of these funerals, the flower arrangements alone can cost 100,000 baht.

But it isn’t these lavish affairs that impress Teerawat. He’s more moved by acts of generosity by poor people. Not long ago, a hard-up family’s two dogs died in a house fire that sent all their possessions up in smoke. With the little money they had left, they paid for a proper funeral service for their dogs.

In a similar show of kindness, when a street dog called Daam (“Black”) died, vendors at a food market where the dog had lived on scraps all chipped in for her funeral. They even brought food for her so she wouldn’t go hungry in the afterlife.

Lolling indolently at the side of the pet crematorium is a stray black mutt, also called Daam. She was dumped last year at the temple with a broken foot and has become something of a resident mascot at cremations. She seems oblivious to the mournful goings-on around her.

Perhaps, Teerawat muses, Daam is here to atone for bad deeds she had committed in her past life. “It’s sad to see dogs suffer and die,” says the businessman, who owns two Rottweilers. “But there’s hope for them in the next life.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!