For some Muslims, the pandemic strips away their ability to mourn

By Hannah Seo and Jonathan Moens

Grieving is difficult. Grieving during a pandemic even more so.

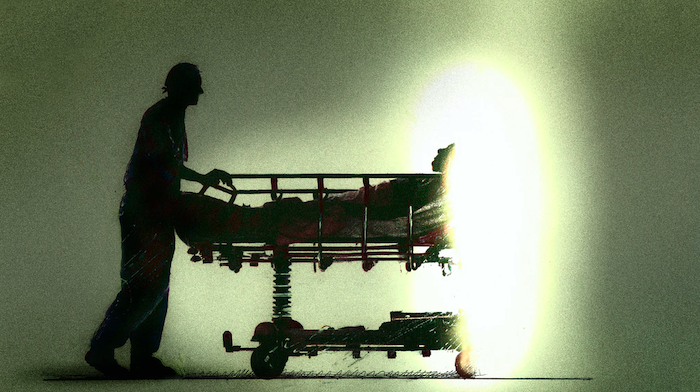

In the Islamic tradition, a person’s passing is marked with an elaborate and symbolic funeral. But what happens to those traditions when the world is put on pause, and when tragedy seems never-ending?

Two Muslim leaders, Ahmed Ali and Payman Amiri, share their stories on how they’ve had to adjust their practices in the time of COVID-19, and how mourning has changed in their communities. They tell Scienceline about the symbolism involved in a typical Islamic funeral, what the transition has been like as the pandemic has ramped up and their experiences of having to deal with the dead while mourners grieve from afar.

Hannah Seo: Each of our lives are marked with landmarks in time: birth, maybe a graduation, perhaps a marriage and a few anniversaries…In the Islamic tradition, one of the most important of these events is actually someone’s death.

Payman Amiri: In our culture and tradition. Dying is part of life.

Hannah Seo: This is Payman Amiri, he’s the chairman at the Islamic Cultural Center of Northern California, where he also works as an Imam. Imams are community leaders in Islam whose duties include teaching the Quran, leading prayers, and generally guiding the members of their communities. One of his duties is managing Islamic funeral services.

Payman Amiri: When somebody dies, you know, we try to sort of do that celebration of life, you know, like very formal in a big event and you just look at these family members that they are traveling with their loss.

Hannah Seo: But since COVID-19 spread across the nation, these funerals look vastly different.

(Guitar music)

Hannah Seo: This is Distanced, Scienceline’s Special Project about how different communities are responding to the coronavirus pandemic. In this installment, we’re looking at how the Islamic community has had to adapt its funeral services, which are important religious events.

Hannah Seo: Islamic funerals aren’t simple. They’re involved, meaningful, and the whole process can span up to several days.

Payman Amiri: The services include the washing of the body for the deceased person has to be washed in a proper way and they get treated with proper spices and herbs is a traditional thing for you. You put it on your skin and then you cover them in a white shroud…

Hannah Seo: He says that all the steps in a proper funeral service are imbued with history and symbolism.

(Guitar fades out)

Payman Amiri: So in our tradition, we believe we came from God, and our return is towards God. And so when you want to give them back, you want them to be washed clean. It has to be a white shroud, it has to be simple because every man and woman will go back to that white shroud. So it’s a symbol of humility.

Hannah Seo: Every aspect of an Islamic funeral is thought through, even the material…

Payman Amiri: It has to be cotton, it’s just everyone is treated equally because, you know, in God’s eye, everyone is equal.

Hannah Seo: Once the body is washed, the next part of the ritual can begin.

Payman Amiri: The body gets transferred to the cemetery, the body gets buried, facing toward Mecca, which is the direction all Muslims pray. And then you get the family members to, to say goodbye by putting flowers in the grave.

Hannah Seo: Or at least, that’s how things are supposed to be done.

(Guitar music)

For Payman, everything changed starting in early February, when he got a surprising call from a family in Santa Clara.

Payman Amiri: When she passed away and her family contacted us. It was the first case of community infection, and so it was a big deal.

Hannah Seo: Azar Ahrabi, a 68-year-old muslim woman from Santa Clara, California was initially diagnosed with pneumonia, but passed away from COVID-19 on March 9th. At the time, people thought she was the very first case of local community transmission of the new coronavirus in the county, but later, local health officials found two other cases who passed away before Azar’s case even came to light.

(Guitar music fade out)

Originally, Payman was supposed to arrange Azar’s funeral. But the virus, and fear of transmission meant that everyone had to take new precautions.

Payman Amiri: What happens if somebody dies with COVID they have to be in body bags, which were a thick bag with a zipper, and the body was in there. And then there are certain people who could only handle the body they have to be fully covered in PPE.

Hannah Seo: PPE is personal protective equipment: masks, gloves, etc. Suddenly mourning went from something close and intimate to something clinical, impersonal.

Payman Amiri: In our tradition, when somebody passes away, you greet the family with hugs and kisses and you hold on tight. And, of course, post COVID-19 nobody could do this.

Hannah Seo: And the moment that helps bring closure to the whole thing is usually a gathering.

Payman Amiri: Usually a lot of people show up in these memorial services, and it’s always the dinner. At the dinner table a lot of people share memories of the deceased person and it sort of helps the survivors put an end to that chapter.

Hannah Seo: But of course the pandemic has rendered these practices impossible. With mosques, funeral homes, and various businesses shut down, that closure is hard to come by.

Payman’s struggles in the throes of the pandemic are not unique — far from it. Imams across countries have had to adjust in ways they never imagined.

Ahmed Ali: We had to go in people’s home, pick up the deceased. We went into the hospitals, we pick up bodies from there.

Hannah Seo: That’s Ahmed Ali, an imam in Brooklyn, NY. He says imams, as leaders of the community, have had to step up and show up for their people. Masjids and mosques, the usual places of worship and congregation for muslims, closed. Communities were left floundering, and only a few people were left to pick up the slack. For Ahmed, it’s been a lot to take over.

Ahmed Ali: Usually the imam’s job is to just lead the funeral prayer and rest the work is done by the funeral home, but all the employees left in the very beginning of this pandemic. And people were scared because they didn’t know how to protect themselves from this virus and nobody knew what actually this virus is. So, they called me and they say, ‘Imam, can you come and help?’

Hannah Seo: Shouldering all the roles himself, Ahmed became body collector, mortician, funeral director — you name it. And at times, it was gruesome.

Ahmed Ali: When we receive the body from hospital, usually they have all the IVs attached. And if the person was in critical condition, then they have tubes inside their mouth. And some time, when we remove the IVs, the blood start coming.

(Guitar music)

Hannah Seo: Ahmed says there were times he’d have to enter storage units with racks of bodies, checking toe tags to find the right person. It took its toll, and the burden was immense.

Ahmed Ali: It’s not an easy thing. So you can say it takes about two hour to wash one body. This was really difficult because picking up a body and taking it into the funeral home then unload it then put on a table, wash it, put inside the piece of cloth and then put it back inside the casket, then take it for the funeral prayer, then go to the cemetery lower down the body inside the grave. So this all work is actually really difficult.

Hannah Seo: If this seems like so incredibly much for one person to take on, that’s because it is. But Ahmed couldn’t turn away…

Ahmed Ali: I didn’t say no because this is a responsibility of an imam, that whenever things go, this kind of pandemic, then we have to show that we actually care for our community.

Hannah Seo: Comforting others is easier said than done, especially when you see your community hurting, with no power to change things.

Payman Amiri: I get emotional when [I know when] I do these services to start with because you see, you know, the family is crying and grieving when you feel for them.

(Guitar music fade out)

Hannah Seo: Recreating that connection and support during the pandemic, a time of intense disconnection, is challenging. The emotional burden of conducting a funeral is hard enough without the impediments of social distancing and Zoom preventing everyone from mourning the way they deserve to.

Ahmed Ali: Well, a lot of family members, they did use the Zoom and FaceTime and other apps to show the funeral service to their families around the world. I think, that’s an honor for me that I was able to help those families.

Hannah Seo: Ahmed Ali has led countless services all by himself, with no mourners or relatives around to claim the decedent as their own.

Ahmed Ali: Whenever I got a body with no family member, then I used to record a clip when we lower the body inside the cemetery.

Hannah Seo: Ahmed recorded these services in case friends or family came later, in case they came and wanted something to remember their loved one’s passing.

Ahmed Ali: But there are many clips I recorded and nobody ever asked for them. It’s sad because, you know, I was leading the prayer, I don’t know that person. But I was just there because, you know, I know that that person is a Muslim and a family to me.

Hannah Seo: With many states reopening, Payman and Ahmed’s lives have returned to some form of normalcy. In fact Payman recently had to organize the burial for another COVID-19 victim; this time, however, he was able to carry out a full service for the grieving family.

Things may have gotten better, but Payman and Ahmed are still anxious about the situation. The worst may be behind them, but helping families process their loss is work that is never done.

Ahmed Ali: I as an imam just was able to stand next to them and tell them that, you know, this is reality of life. And now all we can do is pray for this deceased brother or sister.

(Prayer and guitar music in background)

Hannah Seo: This episode was reported by Jonathan Moens and me, Hannah Seo, for Scienceline. Thanks to both Payman Amiri and Ahmed Ali for sharing their stories.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!