By ALLAN KELLEHEAR

Traditional, mythic accounts of the origin of death extend back to the earliest hunter-gatherer cultures. Usually these stories are morality tales about faithfulness, trust, or the ethical and natural balance of the elements of the world.

According to an African Asante myth, although people did not like the idea or experience of death, they nevertheless embraced it when given the choice, as in the tale of an ancient people who, upon experiencing their first visitation of death, pleaded with God to stop it. God granted this wish, and for three years there was no death. But there were also no births during that time. Unwilling to endure this absence of children, the people beseeched God to return death to them as long as they could have children again.

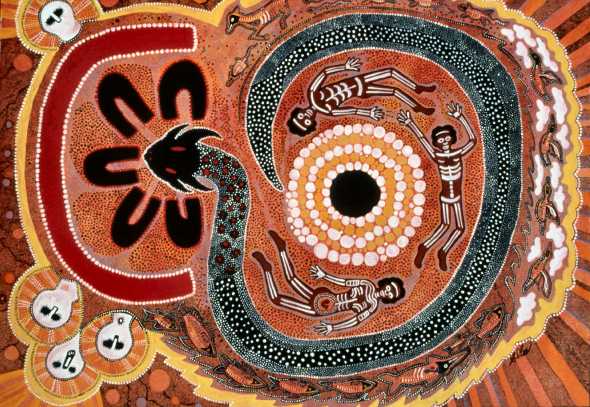

The death myths of aboriginal Australia vary enormously among clans and linguistic groups. Among most of them, however, death is often attributed to magic, misfortune, or to an evil spirit or act. Occasionally death is presented as the punishment for human failure to complete an assignment or achieve a goal assigned by the gods. Still other stories arise from some primordial incident that strikes at the heart of some tribal taboo. Early myths about death frequently bear these moral messages.

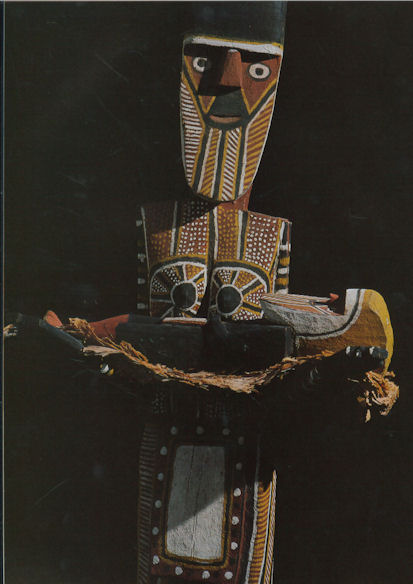

Among the Tiwi of Bathurst and Melville Islands in northern Australia, the advent of death is explained by the Purukapali myth, which recounts a time before death entered the world, when a man lived with his infant son, his wife, and his younger brother. The younger brother was unmarried and had desires for his brother’s wife. He met her alone while she was gathering yams, and they spent the rest of the afternoon in sexual union. During this time, the husband was minding his infant son, who soon became hungry. As the son called for feeding, the husband called in vain for his missing wife. At sunset, the wife and younger man returned to find that the infant son had starved to death. Realizing what had happened, the husband administered a severe beating to his brother, who escaped up to the sky where he became the moon. His injuries can still be seen in the markings of the moon every month. The husband declared that he would die, and, taking the dead infant in his arms, performed a dance—the first ceremony of death—before walking backwards into the sea, never to be seen again.

The Berndts, Australian anthropologists, tell another ancient myth about two men, Moon and Djarbo, who had traveled together for a long while but then fall mortally ill. Moon had a plan to revive them, but Djarbo, believing that Moon’s idea was a trick, rebuffs his friend’s help and soon dies. Moon dies also, but thanks to his plan, he managed to revive himself into a new body every month, whereas Djarbo remained dead. Thus, Moon triumphs over bodily death while the first peoples of that ancient time followed Djarbo’s example, and that is why all humans die.

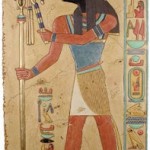

Death As a Being

None of these stories is meant to suggest that aboriginal people do not believe in spiritual immortality. On the contrary, their lore is rich in accounts of immortal lands. These are accounts of the origin of physical rather than spiritual death.

The idea of death as a consequence of human deeds is not universal. The image of death as a being in its own right is common in modern as well as old folklore. In this mythic vein, death is a sentient being, maybe an animal, perhaps even a monster. Sometimes death is disguised, sometimes not. Death enters the world to steal and silence people’s lives. In Europe during the Middle Ages death was widely viewed as a being who came in the night to take children away. Death was a dark, hooded, grisly figure—a grim reaper—with an insatiable thirst for the lives of children. Children were frequently dressed as adults as soon as possible to trick death into looking elsewhere for prey.

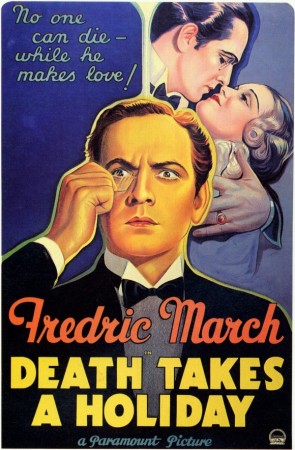

The film industry produced two well-known films, the second a remake of the first, which examined this idea of death as a being who makes daily rounds of collecting the dead: Death Takes a Holiday (1934) and Meet Joe Black (1998), both of which portrayed death as perplexed at his victim’s fear of him. In a wry and ironic plot twist, a young woman falls in love with the male embodiment of death, and it is through an experience of how this love creates earthly attachment that death comes to understand the dread inspired by his appearance.

But the idea of death as a humanlike being is mostly characteristic of traditional folktales that dramatize the human anguish about mortality. By contrast, in the realm of religious ideas, death is regarded less as an identifiable personal being than as an abstract state of being. In the world of myth and legend, this state appears to collide with the human experience of life. As a consequence of human’s nature as celestial beings, it is life on Earth which is sometimes viewed as a type of death. In this way, the question of how death enters the world in turn poses the question of how to understand death as an essential part of the world.

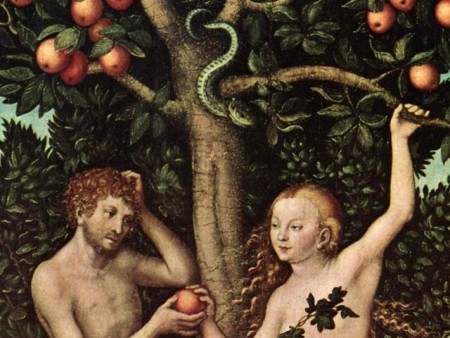

The Garden of Eden

In the book of Genesis, the first man, Adam, wanders through the paradisiacal Garden of Eden. Pitying his solitary nature, God creates the first woman, Eve, from Adam’s rib. Adam and Eve are perfectly happy in the Garden of Eden and enjoy all its bounty with one exception: God prohibits the couple from eating from the Tree of Knowledge.

The Garden of Eden is utopian. Utopia, in its etymological sense, is literally “no place.” It is a perfect, probably spiritual domain for two celestial beings who, bearing the birthmarks of the God who created them, are immortal. These two beings eat from the Tree of Knowledge, which ironically, distracts them from their awareness of God and his omnipresence. As a result of this error, Adam and Eve become the embodiment of forgetfulness of the divine. In other words, they become material beings, as symbolized in their sudden awareness of and shame in their nakedness.

Adam and Eve thus “fall” into the flesh, into the world as it is known, with the entire legacy that embodiment entails: work, suffering, and physical death. Paradoxically, the Tree of Knowledge heralds ignorance of their divine nature, and the fall into flesh signals their sleepwalking indifference to that nature. Human beings therefore need God’s help through the divine mercy of his Son or the sacred texts of the Bible to awaken them to their divine destiny. Without this awakening, the wages of sin are eternal death—an eternal darkness spent in chains of ignorance, a blindness maintained by humans’ attachment to mere earthly concerns and distractions. This famous story thus embodies all the paradoxical elements of creation, implying that human life is actually no life at all, but its opposite: death.

Adam and Eve thus “fall” into the flesh, into the world as it is known, with the entire legacy that embodiment entails: work, suffering, and physical death. Paradoxically, the Tree of Knowledge heralds ignorance of their divine nature, and the fall into flesh signals their sleepwalking indifference to that nature. Human beings therefore need God’s help through the divine mercy of his Son or the sacred texts of the Bible to awaken them to their divine destiny. Without this awakening, the wages of sin are eternal death—an eternal darkness spent in chains of ignorance, a blindness maintained by humans’ attachment to mere earthly concerns and distractions. This famous story thus embodies all the paradoxical elements of creation, implying that human life is actually no life at all, but its opposite: death.

In the kernel of this local creation story lies the archaic analogy of all the great stories about how life is death and death is the beginning of true life. The cycles of life and death are not merely hermeneutic paradoxes across different human cultures, but they are also the fundamental narrative template upon which all the great religions explain how death entered the world and, indeed, became the world.

In Greek mythology, as Mircea Eliade has observed, sleep (Hypnos) and death (Thanatos) are twin brothers. Life is portrayed as a forgetfulness that requires one to remember, or recollect, the structures of reality, eternal truths, the essential forms or ideas of which Plato wrote. Likewise, for postexilic Jews and Christians, death was understood as sleep or a stupor in Sheol, a dreary, gray underworld in the afterlife. The Gnostics often referred to earthly life as drunkenness or oblivion. For Christians, the exhortation was also to wake from the sleep of earthly concerns and desire and to watch and pray. In Buddhist texts, the awakening is a concern for recollection of past lives. The recollection of personal history in the wheel of rebirth is the only hope anyone has of breaking this cycle of eternal return.

Sleep, then, converges with death. Both have been the potent symbols and language used to describe life on earth. It is only through the remembering of human’s divine nature and its purpose, brokered during an earthly life of asceticism or discipline, or perhaps through the negotiation of trials in the afterlife, that one can awaken again and, through this awakening, be born into eternal life.

Modern Accounts

The humanistic trend of twentieth-century social science and philosophy has diverged from this broadly cross-cultural and long-standing view of death as earthly existence and true life as the fruit of earthly death. Contemporary anthropology and psychoanalytic ideas, for example, have argued that these religious ideas constitute a “denial of death.” The anthropologist Ernest Becker and religious studies scholar John Bowker have argued that religions generate creation myths that invert the material reality of death so as to control the anxiety associated with the extinction of personality and relationships.

Like-minded thinkers have argued that philosophical theories which postulate a “ghost in the machine”—a division of the self into a body and a separate spirit or soul—are irrational and unscientific. But, of course, the assumptions underlying these particular objections are themselves not open to empirical testing and examination. Criticism of this kind remains open to similar charges of bias and methodological dogma, and tends, therefore, to be no less speculative than religious views of death.

Beyond the different scientific and religious arguments about how life and death came into the world, and which is which, there are several other traditions of literature about travel between the two domains. Scholars have described the ways in which world religions have accounted for this transit between the two halves of existence—life and death. Often, travel to the “world of the dead” is undertaken as an initiation or as part of a shamanic rite, but at other times and places such otherworldly journeys have been part of ascetic practices of Christians and pagans alike.

Beyond the different scientific and religious arguments about how life and death came into the world, and which is which, there are several other traditions of literature about travel between the two domains. Scholars have described the ways in which world religions have accounted for this transit between the two halves of existence—life and death. Often, travel to the “world of the dead” is undertaken as an initiation or as part of a shamanic rite, but at other times and places such otherworldly journeys have been part of ascetic practices of Christians and pagans alike.

In the past half century psychological, medical, and theological literature has produced major descriptions and analyses of near-death experiences, near-death visions, visions or hallucinations of the bereaved, and altered states of consciousness. Research of this type, particularly in the behavioral, social, and clinical sciences, has reignited debates between those with materialist and religious assumptions about the ultimate basis of reality.

Traditionally confined to the provinces of philosophy and theology, such debates have now seeped into the heretofore metaphysics-resistant precincts of neuroscience, psychology, and medicine. What can these modern psychological and social investigations of otherworldly journeys tell experts about the nature of life and death, and which is which?

The religious studies scholar Ioan Peter Couliano argues that one of the common denominators of the problem of otherworldly journeys is that they appear to be mental journeys, journeys into mental universes and spaces. But such remarks say more about the origin of “mental” as a term of reference than the subject at hand. The glib observation that otherworldly journeys may be mere flights of fancy may in fact only be substituting one ambiguous problem with yet another.

As Couliano himself observes, people in the twenty-first century live in a time of otherworldly pluralism—a time when such journeys have parallels in science and religion, in fantasy and fact, in public and private life.

Conclusion

Death has permeated life from the first stirrings of matter in the known universe—itself a mortal phenomenon, according to the prevailing cosmological theory of contemporary physics. Death came incorporated in the birth of the first star, the first living molecules, the birth of the first mammoth, the first cougar, the first human infant, the first human empire, and the youngest and oldest theory of science itself. Early cultures groped with the meaning of death and its relationship to life. The very naming of each, along with the attendant stories and theories, is an attempt to somehow define and thus master these refractory mysteries. All of the major myths about how death entered the world are, in fact, attempts to penetrate below the obvious.

Most have concluded that Death, like Life, is not a person. Both seem to be stories where the destinations are debatable, even within their own communities of belief, but the reality of the journey is always acknowledged—a continuing and intriguing source of human debate and wonderment.

See also: Afterlife IN Cross-Cultural Perspective ; Australian Aboriginal Religion ; Gods AND Goddesses OF Life AND Death ; Immortality

Complete Article HERE!