— Losing a loved one is stressful enough without having to deal with a botched funeral. Preplanning, due diligence and good communication can head off difficult surprises.

When a loved one dies, the grief experienced by family members may be overwhelming. Even when the deceased was elderly and the death was expected, it can be challenging to move forward with funeral planning and burial preparations. Imagine how much more difficult it can be for a family who loses a loved one unexpectedly.

Horror stories about unscrupulous funeral homes have been front-page fodder for more than a century – see Jessica Mitford’s 1963 book American Way of Death – and I have personally handled more of these cases than I care to think about. When people are dealing with the death of someone close to them, the last thing they should be dealing with is a botched funeral.

Despite strong consumer protection laws and the licensing of funeral home directors, it is still possible to experience bad service from a funeral home. But with good information and careful planning, family members should have their moment to pay their respects with dignity.

Preplanned Funerals Present Best Scenario

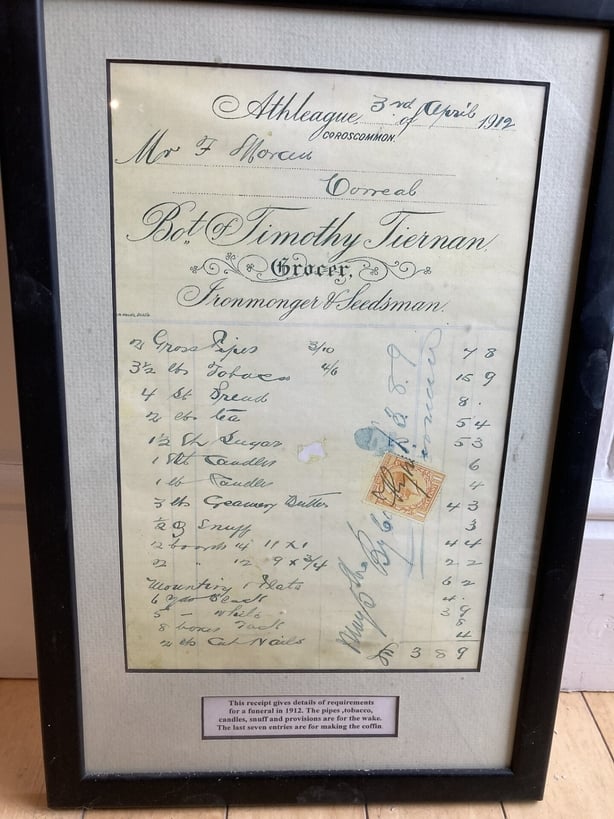

The best scenario is, of course, a preplanned funeral. The deceased has either made arrangements in advance or has left written instructions about how things should be handled. The directive clearly outlines the steps to be taken by loved ones, saving them from having to make those decisions following the death.

It sounds simple and straightforward, but it is not always so simple. Family members owe it to the deceased – and to themselves – to ensure that the provider chosen by the deceased a year or a decade ago is still in business and reputable. Just because the directive names a specific funeral home does not mean that survivors are obligated to entrust the remains to that home. If the named funeral home raises concerns for the family (more about this below), it is far better to move forward with a different funeral home, despite the deceased’s wishes.

Due Diligence When Looking for a Funeral Home Can Head Off Surprises

If the deceased failed to make funeral plans in advance, or if the family believes plans must be changed because of new information they’ve received about the designated funeral home, the process of shopping for a good funeral home begins. It isn’t like shopping for a car: There are no lemon laws or do-overs if they get it wrong. Once a contract for funeral or burial services has been signed and the funeral home has taken possession of a body, it may be impossible to back out of the commitment. Therefore, the more due diligence done beforehand, the better everyone should sleep.

It starts with doing basic research. Read customer reviews. Check for complaints with the Better Business Bureau and state licensing agencies. Look at county records to see if there is a history of lawsuits against the funeral home. The more you know up front, the fewer surprises there should be down the line.

Then meet with representatives of the funeral home to learn about their services. Every funeral home is obligated to provide prospective customers with a menu of choices before having them sign an agreement. If the funeral home staff try to sell you a package, or you feel in any way pressured to make a choice before you have seen their menu, leave the premises and look for another provider.

Don’t Hesitate to Ask Questions and Keep Lines of Communication Open

Ask questions before signing anything. Find out whether the home has received a death certificate for the deceased and, if not, how long it should take to get a certificate following an autopsy or medical examiner’s review. If there will be a cremation, consider asking the home whether they can preserve the body so that it can be viewed prior to the cremation. Make sure you feel comfortable that the funeral home will honor the deceased’s wishes, if preplanning was done, or that they understand and will honor your wishes if no advance directive was created by the deceased.

After you’ve signed an agreement with the funeral home on the package you’ve chosen, the ball is essentially in the funeral home’s court. It will be extremely difficult to undo things if you’re unhappy with its work. Even though there is nothing left for you to do other than wait for the work to be completed, expect to have ongoing communications with the home.

The funeral home should continue to be available to answer your questions, and it should be keeping you apprised of its progress with your case. If you believe that something has not been done correctly, or you have other concerns about the services being performed, representatives of the home should be willing to meet with you to discuss these issues.

Reporting Issues to the Proper Agencies

Unfortunately, even with the best of planning, things can go wrong. If you believe that a funeral home has handled things improperly or violated your trust, you can and should report it to the proper agencies. At the federal level, this would be the Federal Trade Commission. At the state level, it will likely be the appropriate licensing board for the industry. You can also reach out to nonprofit groups such as Funeral Consumers Alliance or the Funeral Consumer Guardian Society.

If you have suffered emotional distress or other injury as a result of a funeral home’s actions, contact an attorney who has experience with these types of cases. The consumer organizations named above may be able to provide referrals.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!