— How Humans Cope With the Awareness of Their Own Death

By Cynthia Vinney, PhD

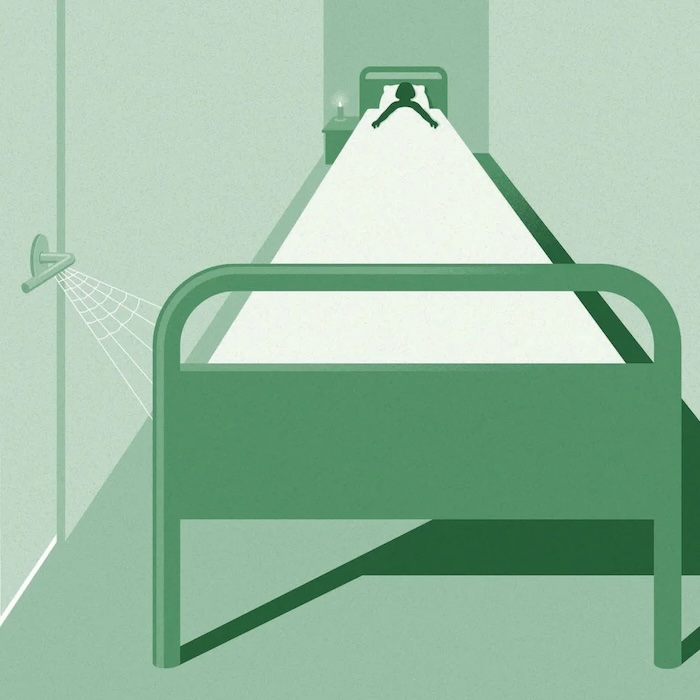

Terror Management Theory (TMT) suggests that human beings are uniquely capable of recognizing their own deaths and therefore they must manage the existential anxiety and fear that comes with knowing their time on Earth is limited.

The theory was developed by psychological researchers Jeff Greenberg, Sheldon Solomon, and Tom Pyszczynski, who published the first TMT article in 1986.1 They based TMT on the writings of Ernest Becker, who spoke of the need to protect against the universality of the terror of death.

In this article, we’ll review key concepts of TMT, look at empirical evidence in support of TMT, explore real-life examples of TMT, and discuss how it is used across different fields.

Key Concepts and Principles of Terror Management Theory

Terror Management Theory explains that people protect themselves against mortality salience, or awareness of one’s own death, based on whether their fears are conscious or unconscious.

If they’re conscious, people combat them through proximal defenses by eliminating the threat from their conscious awareness. If they’re unconscious, distal defenses, such as a sense of meaning, like cultural worldviews, or value, like self-esteem, diminish unconscious concerns about death.2

Cultural worldviews and self-esteem are key concepts of TMT. They are both central to protection against mortality salience. David Tzall, PsyD, a licensed psychologist in New York, notes, “TMT suggests that individuals gravitate towards and defend their cultural worldviews more strongly when confronted with thoughts of mortality.”

Through cultural worldviews, people can achieve literal or symbolic immortality. Literal immortality, the idea that we will continue to exist after our death, is usually the domain of religious cultural worldviews. Symbolic immortality is the idea that something greater than oneself continues to exist after their death, such as families, monuments, books, paintings, or anything else that continues to exist after they’re gone.

TMT suggests that individuals gravitate towards and defend their cultural worldviews more strongly when confronted with thoughts of mortality.

Self-esteem plays a significant role in TMT too. “When faced with the awareness of death,” Tzall says, “people often engage in activities or behaviors that boost their self-esteem as a way to manage the anxiety associated with mortality.” In so doing, they provide the sense that they are a valuable participant in a meaningful universe.3

These have led to two important hypotheses in TMT. First, the mortality salience hypothesis says we have negative reactions to individuals from a different group, called “outgroupers,” who present a threat to our group, and have positive reactions to those who represent our cultural values, referred to as “ingroupers.” Second, the anxiety-buffer hypothesis says strengthening our anxiety-buffer by, for example, boosting self-esteem, should reduce the individual’s anxiety about death.4

Review of Empirical Evidence Supporting Terror Management Theory

There are over 500 studies conducted in countries around the world supporting TMT. For example, one study found that raising self-esteem reduces anxiety in response to images of death.5 Similarly, increasing self-esteem reduces the effects of mortality salience on the defense of one’s worldview. When the researchers provided positive personality feedback instead of neutral feedback, their preference for a US-based author was equivalent to that of the control group, whereas participants who received neutral feedback far exceeded the control group in preference for the author.6

Another study found that worldview threats increase accessibility of death thoughts. When Canadians were exposed to a website that either derogated Canadian values or Australian values, they had far more thoughts about death when they encountered the anti-Canadian information.7

Real-Life Examples Illustrating the Application of Terror Management Theory

There are many ways that terror management theory can be applied to real life. Tzall provides some examples, such as “religion where religious beliefs and practices offer explanations for life’s meaning, purpose, and what happens after death. People will turn to religion to alleviate existential anxiety and find solace in the idea of an afterlife.”

Believing in religion may provide a chance at literal immortality, but beyond that, it can provide a cultural worldview that brings meaning and purpose to life and can alleviate mortality salience.

Likewise, Tzall gives the example of belonging to a nation that “provides a sense of identity and belonging, which can help individuals feel connected to something enduring. People may strive to achieve success, create meaningful relationships, or contribute to society in ways that leave a lasting impact.” There are all sorts of ways that people can find meaning and achieve symbolic immortality, including being part of a nation that will go on after their death.

In addition to feeling like a part of the nation, people will want to put their own stamp on the nation whether through success in industry, meaningful relationships that have a lasting impact, or other options like volunteering, having a family, or writing a book.

Implications of Terror Management Theory across Different Fields

Different fields can use TMT in different ways. For example, the most obvious may be the field of therapy and counseling. As Tzall explains, “TMT sheds light on how individuals’ psychological well-being, self-esteem, and behavior are influenced by thoughts of mortality.” Tzall continues, this “can help therapists understand existential anxiety and develop strategies to address it.”

The theory can similarly be used in marketing and advertising, but the emphasis is different. “TMT can inform advertising strategies that tap into consumers’ desires for symbolic immortality,” Tzall says. In this conception, marketers and advertisers advertise goods or services in a way that communicates their desire for symbolic immortality can be met.

Similarly, political science “can help explain the polarization of political ideologies,” explains Tzall, “and the ways in which leaders appeal to their followers’ existential concerns to gain support.” Through cultural worldviews that appreciate others like them but reject others that are not like them, leaders can exploit their followers and even lead them to rise up against others that do not agree with them, in wars, conflicts, or events like January 6th, where a small group of like-minded citizens stormed Congress.

Significance of Terror Management Theory in Understanding Human Behavior and Beliefs

Though some studies about TMT have failed to be replicated, Terror Management Theory has continued to resonate with many people. And researchers still use it to describe various events.

For example, a group of researchers used TMT to detail the COVID-19 pandemic during its height, explaining that regardless of how deadly the virus is, the risk of dying was highly salient.8 As a result, in response to the pandemic, people responded to the constant fear of death in both proximal and distal ways.

In proximal ways: drinking and eating in excess to arguing that the virus isn’t nearly as lethal as health experts claim. And in distal ways: affirming an individual’s cultural worldview to maximizing one’s self-esteem, in line with the TMT literature. As threats that remind us of our own deaths continue and expand, TMT will continue to be a leading source of understanding human behavior and beliefs.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!