By Thomas West

Sadly enough, everyone must contend with death at one point or another. Given its ubiquity, it’s unsurprising that the movies have engaged with questions of death, dying, and grief, often with great effect. At their best, such films tug on the heartstrings and use cinematic storytelling to grapple with the broader questions that death inevitably raises. Just as importantly, for many people, films about death and dying are also invaluable tools for learning how to work through and process the sometimes overwhelming power of grief and loss.

‘City of Angels’

Nicolas Cage and Meg Ryan have astonishing chemistry in the beloved ‘90s movie City of Angels. Cage portrays Seth, an angel who falls in love with a human woman (Dr. Maggie Rice, played by Ryan) and, after sacrificing his immortality, learns what it means to be human. It hits many of the notes one would expect from a romantic drama of this sort, but it also does something a bit more: Using its story of an angel to ask the viewer to examine what it means to be human and how it is possible to make one’s peace with the inevitability of death.

‘Terms of Endearment’

Shirley MacLaine gives one of the best performances of her career in Terms of Endearment, in which she plays Aurora Greenway, a woman with a close but complex relationship with her daughter, Emma. Things become particularly difficult when the latter develops terminal cancer, leading to some of the most emotionally wrenching and heartbreaking moments of the 1980s. It is anchored by the strong performances of MacLaine and co-star Debra Winger, and the film accurately captures how terminal illness can impact even the strongest of relationships, including the ones between a mother and her daughter.

‘P.S. I Love You’

At first blush, the central conceit of P.S. I Love You — in which a husband leaves behind a number of messages to his widow to keep her from being mired in grief — might seem ridiculous. However, one can’t help but admire the film’s commitment to this idea, which ends up being a sweet little melodrama (even if the critics disapproved). Though Hilary Swank was better known for her serious dramatic roles before this film, she does quite well as a romantic lead, and the film explores the difficulties of navigating love and loss.

‘Marley & Me’

If there’s one thing sure to evoke tears, it’s a story about a dog. Perhaps no film pulls this off like Marley & Me, the film based on the bestselling memoir by John Grogan. Though Owen Wilson and Jennifer Aniston are the putative stars, the yellow Labrador retriever Marley is the heart and soul of the film. Much like Old Yeller, the film is as heartbreaking as it is funny, but because of this, it is the ideal film for those who need to work through their own loss of a beloved family animal companion.

‘Soul’

The genius of the Pixar method of filmmaking lies in its ability to use the beauty of animation to explore weighty philosophical and emotional issues. Soul, for example, follows an aspiring musician who falls into a coma before he can realize his dream and tries to escape the inevitability of death. Like so many of the studio’s other beloved films, it doesn’t beat the viewer over the head with its messages; instead, it uses its gentle, soft story and the combination of beautiful animation and talented voice cast to guide them into a deeper understanding and appreciation of life and its inevitable end.

‘The Sixth Sense’

These days, the works of M. Night Shyamalan have become quite limited due to his over-reliance on a twist ending. However, The Sixth Sense remains one of his most notable creations, thanks to inspired performances from Bruce Willis, Haley Joel Osment, and Toni Collette. Moreover, its story about a boy who can commune with the dead retains its raw emotional power. Though it often veers into the realm of unsettling horror, it just as frequently ventures into more somber and thoughtful territory, asking what it means to grieve and what it means to move on from loss.

‘Meet Joe Black’

Meet Joe Black is one of those unusual films that could have only come out in the 1990s, focusing as it does on a businessman who encounters Death who, in turn, wants to grasp the human experience. Things get more complicated once Death — in the form of a young man named Joe Black — falls in love with the businessman’s daughter. It stars some of the biggest names of the decade, including Brad Pitt and Anthony Hopkins. Though it is a bit overlong (it runs over three hours), there is still something remarkably touching and sensitive about the film’s engagement with the question of what makes one human.

‘The Fault in Our Stars’

There’s something uniquely poignant and heartbreaking about films that focus on two young people who find love despite suffering from terminal illnesses. This premise is at the heart of the film The Fault in Our Stars, which focuses on Hazel and Gus, two cancer patients who fall in love despite their bleak prognoses. In a less competent film, the story would have felt trite and cliche, but thanks to the memorable performances from Shailene Woodley and Ansel Elgort, it becomes instead a moving testament to the power of love to give meaning to a life.

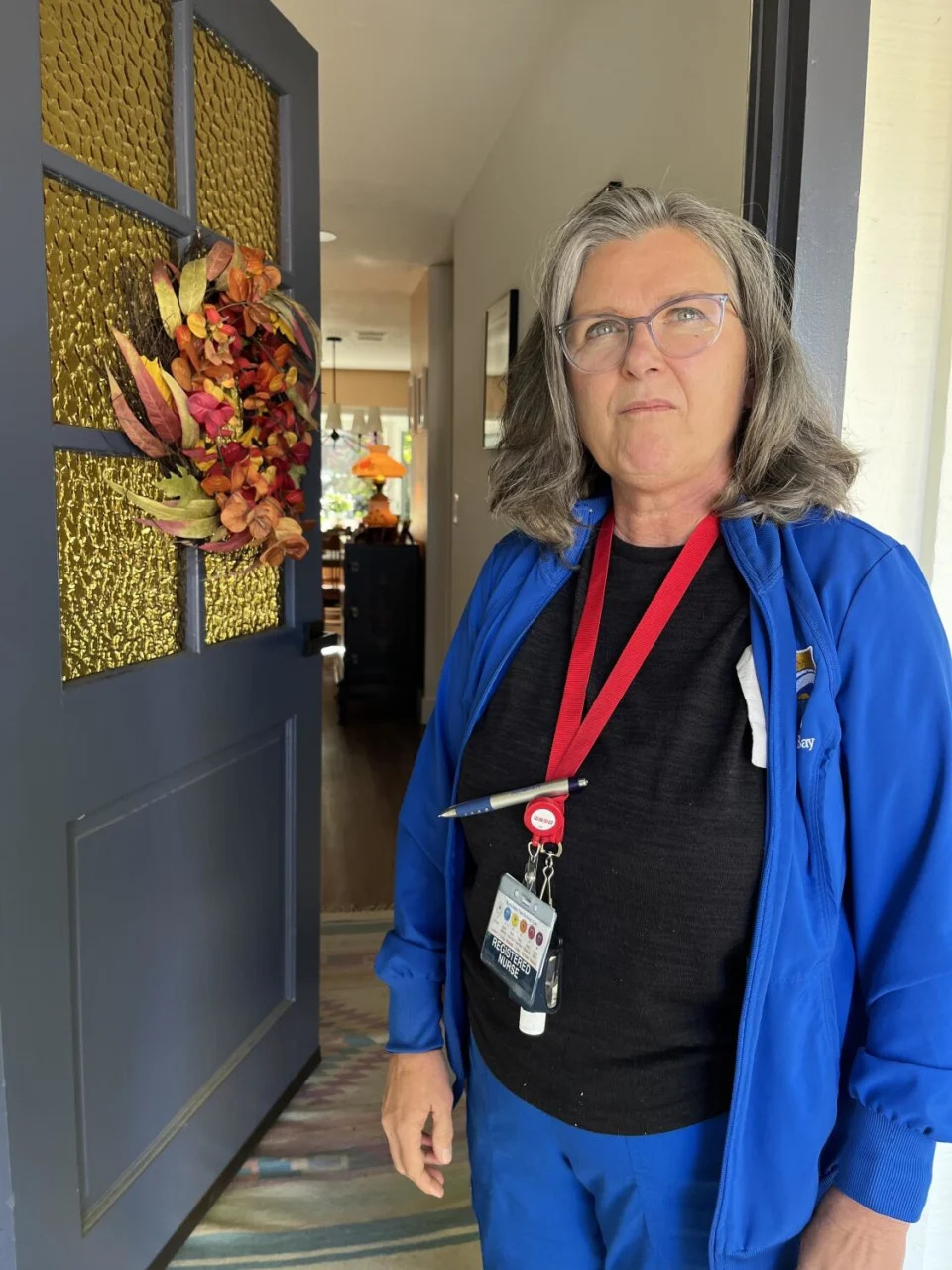

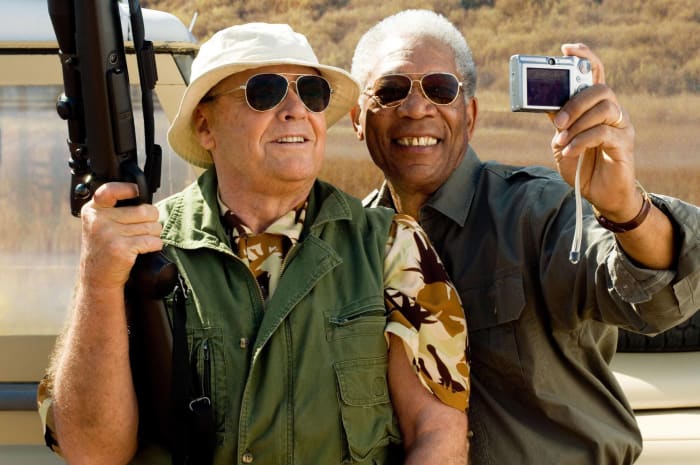

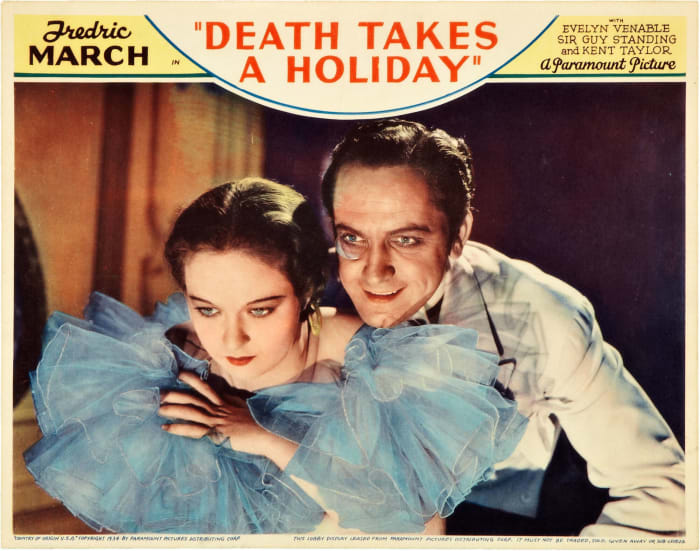

‘Death Takes a Holiday’

The Pre-Code era of Hollywood was a particularly fertile period for the industry, known for generating some remarkable and adventurous movies. For example, Death Takes a Holiday, as its title suggests, focuses on Death as he decides to become a human for a time. While in his mortal body, he falls in love with a mortal woman. This might sound a bit morbid, and it is, but somehow, the film manages to make it work, thanks in no small part to the performance of Fredric March as Death (and his human form, Prince Sirki).

‘The Lovely Bones’

Though Peter Jackson is best known for his Lord of the Rings trilogy, he has also earned well-deserved praise for several smaller, more intimate projects. One of the most notable of these is The Lovely Bones, based on the novel of the same name by Alice Sebold. It’s a haunting and beautifully-told movie about a young woman who grapples with her own death and what to do from the in-between self in which she finds herself. The film deals with some heavy and powerful topics, but thanks to Jackson’s direction and Saoirse Ronan’s performance, it never becomes the cliche it could have been.

<h2″>’The Land Before Time’

The animated films of Don Bluth are rightly regarded as the more emotionally mature counterpart to Disney (for whom he once worked), and few ‘80s and ‘90s kids weren’t traumatized by The Land Before Time. The death of Littlefoot’s mother near the beginning of the film is heartbreaking in itself, but it is also wrenching to watch the poor young dinosaur have to come to terms with her loss. Nevertheless, Bluth’s genius lies in his ability to make death in all its devastation explicable and understandable for his young audience, giving them a means of working through the unimaginable.

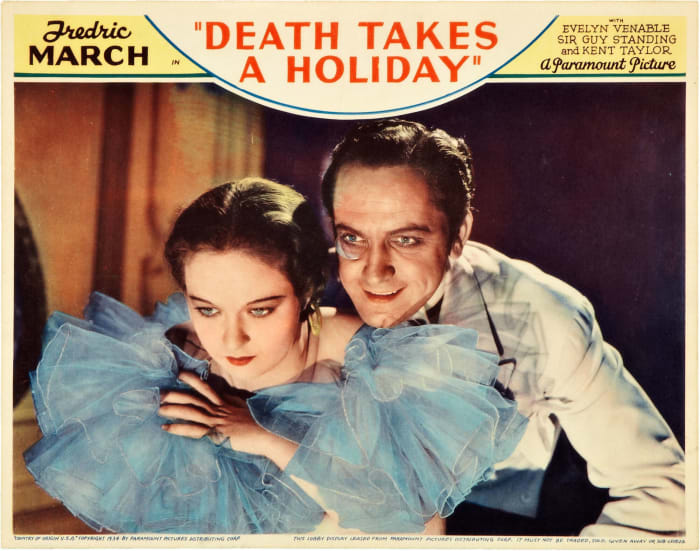

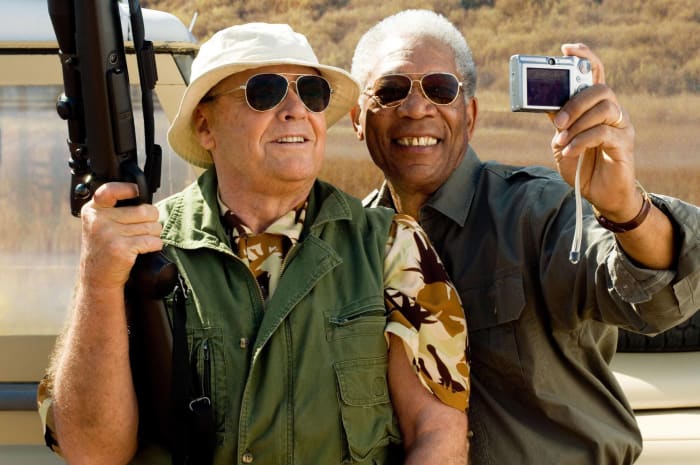

‘The Bucket List’

Morgan Freeman and Jack Nicholson are perfectly cast as Carter and Edward, two dying men who decide to start doing the activities they have wanted to try before they die. It’s an unquestionably sentimental movie, but this is precisely what makes it such a joy to watch Nicholson and Freeman portray two curmudgeonly but adventurous older men. It’s also a film that reminds the viewer of the importance of making the most out of the time that one has, whether it’s months or years.

‘Ghost’

During the height of his career, the late Patrick Swayze was one of Hollywood’s biggest heartthrobs. He conveyed a mix of assurance, swagger, and sensitivity, which are very much on display in the 1990 film Ghost. In the film, he plays Sam Wheat, a man killed only to return as a ghost. He then joins forces with a medium (played by Whoopi Goldberg) to reunite with his beloved Molly (Demi Moore). Its premise might be more than a little far-fetched, but somehow, the film makes it work, primarily because of the undeniable chemistry between Swayze and Moore, who manage to sell its outlandish premise.&

‘The Others’

Nicole Kidman is one of her generation’s finest actresses, and she performs remarkably in The Others. She portrays Grace Stewart, a mother desperate to protect her children from the malevolent entity that seems to have inhabited their house. As the film goes on, however, it becomes clear that not all is at all as it seems, and the film skillfully keeps the viewer guessing until the very end. The final twist is as heartbreaking as it is terrifying, and it allows Kidman to reach new heights in terms of her performance.

‘Love Story’

Love Story is, in some ways, the exemplary 1970s romantic drama. Starring Ryan O’Neal and Ali MacGraw as a young married couple, Oliver and Jenny, who fall in love over the opposition of his parents and their significant class differences. Things veer into tragedy when it’s revealed that Jenny is dying from cancer, leading to Oliver’s reconciliation with his father. In a less capable film, such a story would be trite or treacly. Instead, thanks to a competent script, strong direction, and remarkable performances, it manages to be something stronger than the book on which it’s based, and it deserves its reputation as one of the best love movies ever made.

‘Steel Magnolias’

If there’s one film that is the epitome of a tear-jerker, it would be Steel Magnolias. At the center of the story is the bond between Julia Roberts’ Shelby and Sally Field’s M’Lynn Eatento, a daughter and her mother who have to cope with the former’s failing health and her desire to start a family. The film is filled to bursting with great performances from the likes of Olympia Dukakis, Shirley MacLaine, and Daryl Hannah and, while also uproariously funny, it isn’t afraid to wear its heart on its sleeve, and this is precisely what makes it so enduringly popular and beloved.

‘The Farewell’

While Awkwafina might be best known for her many comedic roles, she has also shown dramatic range, particularly in The Farewell. She plays Billi Wang, a young woman who returns to China once she learns her beloved grandmother is dying. It’s a rich and textured film, particularly since the family refuses to tell the grandmother, Nai Nai, the truth about her diagnosis. This is the type of film designed to be a tear-jerker, but it also engages with several other issues, particularly concerning the conflicts that emerge between second-generation Americans and their first-generation parents and grandparents.

‘A Walk to Remember’

For all that it might be more than a little trite and predictable, there is still something moving about A Walk to Remember. After all, this is a film that focuses on a poignant teen romance between Landon Carter and Jamie Sullivan, the latter of whom is suffering from leukemia. It hits all the right notes, and there is no small amount of chemistry between Shane West and Mandy Moore. Just as importantly, the film also has some genuinely moving moments, particularly when Moore’s Jamie discusses her faith and what she thinks awaits her after death.

‘After Yang’

After Yang, like the very best of science fiction, grapples with some of the biggest ideas that occupy the human imagination. In this case, the film uses the story of one family’s sense of loss over a robotic teenage boy to explore what it means to be human and just what, if anything, separates nonhumans from humans. It’s a remarkably subtle film, eschewing the bombast often associated with the genre. It also features some truly evocative and heartbreaking performances, particularly from Colin Farrell, who plays Jake, the father trying to bring Yang back to life so that his daughter can have a companion.

‘Coco’

As a studio, Pixar has always excelled at crafting exquisitely beautiful and emotionally poignant feature films, and Coco remains one of their best to date. When young Miguel wanders into the Land of the Dead, he finds that he must return home soon or risk being trapped there forever. While there, he has to grapple with some unfortunate truths about his family’s history and learn about the value of grappling with grief and loss. The film is the perfect blend of vibrant animation and poignant emotional truth, with characters one can’t help but love.<

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/pmn/CWBUGU4ERJGLJDTQDWY3BIUAOA.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/pmn/EDUE57BCVJEIXEKDXC336U32RI.jpg)