— And Why You Should, Too

Most people don’t want to think about preparing for death. But we’re all “future corpses” and need to plan accordingly.

I love the illusion of immortality. The $18 billion anti-aging market gets a portion of my weekly paycheck, and the belief that I just might stop my biological clock from ticking quashes any qualms I might have about spending my hard-earned money on a bevy of beauty products. I slather on sunscreen—atop layers of self-tanner, of course—to keep my skin from wrinkling, avoid both alcohol and sugar to keep the weight off, and practice Pilates to keep my spine young and flexible. Despite the increasingly popular gray-hair trend, I treat my locks the old-fashioned way: I line my hall closet with boxes of bleach-blonde drugstore hair dye and avoid looking at my roots under bright lights between colorings.

Keeping death at arm’s length in modern America means not only keeping its markers off the body, but its specter far from the home. A mere century and a half ago, American funerals were mostly family affairs, the body displayed for visitation in the parlor of the home and then buried on family property or in a nearby churchyard. It was only when embalming became popular—following the two-week cross-country viewing of President Abraham Lincoln’s body after his untimely assassination in 1865—that dealing with death became a professional affair, the purview of the undertaker, mortician, and funeral home. Norms shifted accordingly, and by the early 20th century, even the Ladies Home Journal took a stance against death being allowed in the domestic sphere. The publication’s editor banished Victorian-era front parlors from the magazine’s pages and rechristened those spaces as “living rooms” meant for interaction with anyone other than dead family members. Parlors were “perceived as dark, gloomy, and oppressive,” according to one architecture professor in a 1995 Washington Post article about the evolution of living rooms.

Of course, no matter how hard we try to stop the clock or to sweep the shadow of death from our doorsteps, the human body will not last forever. Each and every one of us will die, and, when we do, someone—if we haven’t made arrangements—will have to deal with our funeral expenses. So, despite how uncomfortable people may feel about contending with their eventual death, pre-planning for the end of your life will save your loved ones from facing the distress of making huge financial decisions at a time of loss and grieving. A few simple steps and family conversations can go a long way in preventing additional stressors.

In the past few years, I’ve faced the deaths of several family members, including that of my 94-year-old grandfather, who struggled with dementia at the end of his life, in January 2017, followed by that of my 67-year-old father-in-law in August 2019. How their deaths were handled could not have differed more.

My grandfather, a lifelong Baltimore Catholic, passed away in a hospital. He had pre-planned for his funeral arrangements, which followed the schema of practically every funeral I have ever attended. The funeral parlor embalmed, made up, and laid out his body. My family members and I hosted visiting hours at the funeral home for two days to greet mourners and spend time together looking at photos of my grandfather’s life. Each of us approached the kneeler in front of his casket one by one to pay our respects. On the second day, a pastor from my grandfather’s parish led a service, which included readings by my mother and her sister. The attendees then headed to their cars and followed the hearse for the procession to the cemetery where, after a few words from a religious official, we watched the coffin get lowered into the ground. These final ceremonial moments in the proximity of my grandfather’s body allowed for sufficient grieving and provided me with a sense of closure about the end of my grandfather’s life. Afterwards, we gathered for lunch at a waterfront seafood restaurant

But when my father-in-law Rob died unexpectedly, everything felt terribly wrong. His neighbors in Oregon—across the country from where my husband and I live in Massachusetts—found his body after he failed to walk his dog for several days. The police in Oregon made the required calls to reach my husband, Rob’s next of kin, in order to make the arrangements. Over the next few days, in the throes of bereavement, my husband juggled the many challenges that come with laying to rest someone who hadn’t left behind any instructions for the living for how to handle their death.

Unlike my grandfather, Rob had no money set aside to pay for his arrangements. No one in the family knew how he wished to be memorialized. And even if we had known his wishes, we did not have much money of our own to spend. His body ended up at the Pacific View Memorial Home in Lincoln City, Oregon. My husband and his brother paid $1,095 for his cremation and $15 for a cardboard box for the remains. I stayed home in Boston with our three young daughters while my husband went to clean out Rob’s trailer and receive Rob’s ashes, which he released from a cliff into the ocean below. I still grieve the fact that I never got to say goodbye.

The shame of how poorly Rob’s life ended causes my husband and me pain to this day. On our most recent anniversary, we avoided looking at our wedding album because seeing photos of Rob felt too painful. We cried in one another’s arms, discussing how he deserved not only more time to live, but a far better memorial. Reflecting on these two deaths convinced me that I needed to make a plan to ensure that my family will know what to do when I die. But I had no idea how to actually take action. I put the item “death planning” on my long term to-do list, alongside items like “kids’ college savings” and “look into solar panels”—you know, the type of things that can always “wait until later” (whether that’s true or not) compared to more pressing matters, like putting food on the table, paying the bills, driving the kids around, and everything else it takes to keep a young family afloat.

The most terrifying vision of death I can conjure has nothing to do with, say, violence or disaster. Instead, in this rather banal vision, my husband passes away before me in a hospital bed. A flat green line appears on a monitor accompanied by a long piercing beep—and I am left to live without him for the first time since we met when I was 21. Between this unnerving thought and the fact that I really had no idea where to begin, no wonder I postponed death planning—everything from legal documents to funeral arrangements—over and over again until, finally, last spring, a lawyer set me straight.

“You have three minor children and no will?” he asked, sounding more than a little incredulous. I felt taken aback by his tone but quickly understood the urgency when he explained that, without this document in place, our children would be put in the hands of the Massachusetts legal system if we passed away. I found the thought of my school-aged girls being at the mercy of the Massachusetts Department of Children and Families absolutely horrifying given this institution’s history of overlooking and even enabling sex trafficking and child abuse.

The attorney I hired to write my will also emphasized the importance of term life insurance. I had previously thought of life insurance as a way to cover burial costs and funeral expenses, but during this appointment, I came to understand that these policies would cover my children’s basic expenses until they become financially independent adults. I see how society treats those in need. If I don’t plan for my children’s living expenses, I know that no safety net out there will catch them.

The day after my meeting with the lawyer, I began the process of taking out a $1 million life insurance policy. This seems like an overwhelming amount of money, but it’s what would be needed to provide for our children—their food, clothing, extracurricular activities, preventative health care, and more—until my youngest, now 7, turns 22. My husband and I will pay about $1,000 a year for this policy, but it is necessary in a country where family is made to be the strongest social safety net.

All in all, I tried to keep these conversations businesslike and non-emotional, but tears came to my eyes and my voice cracked more than a few times. I feel like I have done my duty as a mother in ensuring that our children get at least some financial stability if I cannot personally take care of them.

With the will and insurance out of the way, I could finally get to the “fun” part: contemplating my own funeral and burial. I might not know when my life will end, but I can at least plan my memorial service and decide where my body will rest.

Even prior to starting this journey into serious pre-planning, I had a place in mind: Forest Hills Cemetery in Boston. This 275-acre garden cemetery, founded in 1848, features a rolling landscape, Victorian and contemporary sculptures, historic markers, and a central lake. It may sound strange to modern ears to spend one’s leisure time amongst the dead, but I have always considered Forest Hills less of a graveyard and more of a park, and I go walking there at least weekly. And, in fact, that’s what its designers intended: during the mid 19th century, garden cemeteries like Forest Hills not only solved the problem of crowding in urban churchyard burial grounds, but their beautifully manicured grounds also made them a “regular gathering places for strolling and picnicking.”

Because Forest Hills serves as the final resting place of many of Boston’s elite, I assumed this option would be out of my financial reach. But I decided to make an appointment with the cemetery office to find out what it would take to land my dream burial space.

For the first part of my visit, I joined the Assistant Director of Operations at Forest Hills to get information on all of the available options. Burial spaces range from $3,950 for a grave with a flat marker—perhaps, perversely, the most affordable route to land ownership in Boston’s exorbitantly priced and low-inventory real estate market—up to $60,000 for above-ground internment in the exclusive Dearborn Pavilion. Full-casket burials cost $2,300, while cremation burials are set at $1,500; adult cremation alone, sans burial, costs only $435. My visit—which was, dare I say, delightful—ended with a tour of the grounds, during which my guide pointed out the burial sites of the cemetery’s most famous denizens.

None of these prices set off alarm bells. I learned that financing is much like a mortgage. We could put a third down for a plot and pay the rest later. For basically $1,300, my husband and I can secure a shared spot for two urns, one for my remains and one for his. If we buy our plots in advance, we can absolutely afford to place our remains in Forest Hills, a place that has brought us great joy in life.

But before the burial comes the funeral, which—like any good party—comes at a price: the funeral home, the site for the embalming, the casket, and the cosmetic treatment of the body can all add up. I definitely want the royal treatment when I die—ideally, my mourners will find me looking youthful and gorgeous with a perfectly made-up face and a Victoria’s Secret model body, laid to rest in an elegant satin-lined casket à la Stephanie Seymour in the Guns N’ Roses “November Rain” video—but I realize that my money may be better put to use in life than in death.

How much might my dream funeral cost? At the funeral home nearest me that actually had prices listed online, a “complete traditional funeral service” including visitation, embalming, body preparation, and hearse costs $5,795. (While the Federal Trade Commission is currently considering making online price lists the law, many funeral homes still want the customer to get in touch with someone who will persuade you to spend a little bit more on your loved one’s arrangements than you had initially planned.) That $5,795 package does not include a casket, though the funeral home does provide a price list for caskets, ranging from $850 for a flat cloth-covered particle board to an $8,690 solid bronze model. Since the funeral home cannot legally require me to purchase a casket from their stock, I could also shop around on my own, perhaps even through Costco or Amazon.

Technically, no one even has to use a funeral home, at least in my state of Massachusetts. But even if I elect the more fiscally conservative option of having my body cremated at Forest Hills Cemetery, bypassing embalming and viewing entirely, I still need transportation from my place of death to the crematorium. For example, if I pass away in a nursing home, the facility would expect someone to quickly remove my body from the premises. My friends and family can legally take care of this themselves to save a few bucks, but do I really want them to have to find a sizable container and vehicle on the fly when funeral homes have workers on call 24/7 to take care of this?

I hope that, by the time I die, I have made all of these arrangements, so my family can focus on dealing with their emotions and then getting on with their lives. Despite all my planning, the uncertainty of death itself still frightens me.

Will my mind simply shut off, like the black screen at the end of the series finale of The Sopranos? Will I turn into a ghost, perhaps floating above my body and then hovering around the spaces I inhabited in life? Will a Virgil-like figure guide me through Inferno, Purgatorio, and Paradiso? What scares me the most? Not knowing how my last breath will feel. Will I gasp, trying to hold on, or will I feel relaxed? I like what True Detective’s Rustin Cohle, who spends many of his work hours—and a great deal of personal ones as well—looking at photographs of the deceased, puts forth: “They welcomed it. Not at first, but right there in the last instant. It’s an unmistakable relief. See, ’cause they were afraid, and now they saw for the very first time how easy it was to just let go.” I hope it’s easy.

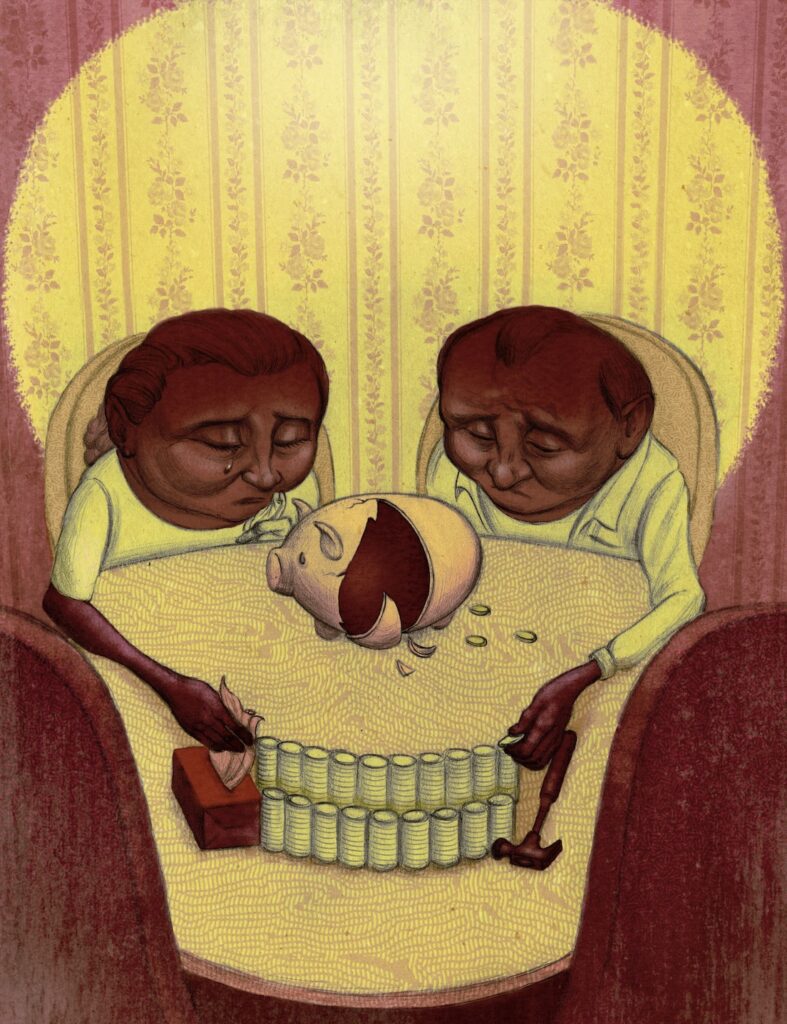

It seems that most people don’t want to think about death planning. Victoria J. Haneman, a professor of trusts and estates, has noted that an estimated 70 percent of deceased people are found not to have done estate or burial planning. And this creates the perfect storm when emotions take hold during the aftermath of someone’s death. Without such planning, many families are put in a precarious financial situation.

Haneman’s 2021 article “Funeral Poverty,” published by the University of Richmond Law Review, lays out the financial impact of the American funeral on families. The average cost of an adult funeral with a viewing exceeds $9,000. This fact is all the more remarkable, Haneman points out, considering that 40 percent of American families say they would struggle to cover an emergency $400 expense. Whatever their finances, the bereaved are in an emotional state that makes for a “vulnerable consumer who is unlikely to be price sensitive and is susceptible to emotional manipulation” at the time of purchase. After all, who wants to cheap out on a particle board casket for a beloved relative—especially at a time when you are probably thinking on a loop about how much you loved them, how much you will miss them, or perhaps how poorly you feel for not treating them better or spending more time with them? In a society that often equates spending with love, financing an elegant funeral may symbolize affection or atonement for the bereaved.

But what if you simply can’t afford it? Haneman writes: “When all potential resources have been exhausted … the last remaining options are to beg, borrow, or surrender” the body. In recent years, online crowdfunding has become a popular means of fundraising for funeral expenses. GoFundMe staff even coaches people on how to make their pleas go viral. Prior to learning the true cost of funerals, when I would see these campaigns on my social media, I didn’t understand exactly why families needed the money. Now, I make a small donation whenever I can.

Another option is borrowing, either via credit card or, for those with bad credit, a loan with an interest rate of up to nearly 36 percent (for comparison, interest rates are around 7 percent on average for a home mortgage or 20 percent for a used car for someone with a low credit score). Families can also surrender the deceased, a situation which, depending on the state, results in either cremation or the burial of remains in a common grave. It’s one thing to surrender the body to the state; in some cases, bodies are never claimed by anyone. While the United States does not track the burial of unclaimed bodies, the Washington Post reported in 2021 that these indigent burials are the fate of tens of thousands of Americans each year.

Desperate and grieving families may become vulnerable to a far less savory option: non-transplant tissue banks. While organ donation for transplants is closely regulated, these unregulated “chop shops” dissect the bodies, sometimes even dismembering them with a chainsaw, then sell the parts, for profit, to medical researchers and even unspecified “other buyers.” A 2017 Reuters investigation detailed the corruption endemic to the commercial market for bodies. They solicit the donation of a corpse, promising that, after organs and cadaver tissues head to medical facilities, they will cremate the rest of the body and return the ashes to the family. But sometimes families don’t get back what they expected from these fraudulent companies.

What solutions exist to mitigate funeral poverty and debt? In 2021, FEMA dedicated $2 billion in funeral expense reimbursement to those who lost a loved one to COVID-19. With proper documentation, families can receive up to $9,000 in relief. (Compare this to the $255 death benefit—a maximum dollar amount that has been capped since 1954—received by the spouse of the deceased from Social Security.) The FEMA funeral benefit appears to be ending in September 2025.

Birth and death constitute the two life events that all people, since time immemorial, have in common. Since the public currently provides funding for nearly half of all births, why not socialize the cost of funerals for everyone? While some states provide financial assistance for low-income people, these funds fall far short of the national average funeral cost of $9,000. Why should anyone go through financial distress because of the death of a loved one? When mourners can gather together at a funeral and move through the grief cycle together, they can more readily move towards acceptance and continue on with their lives.

FUTURE CORPSE. A black T-shirt with these two words in capital letters across the chest lies at the back of my dresser. I bought it a year ago but have yet to muster the courage to wear it.

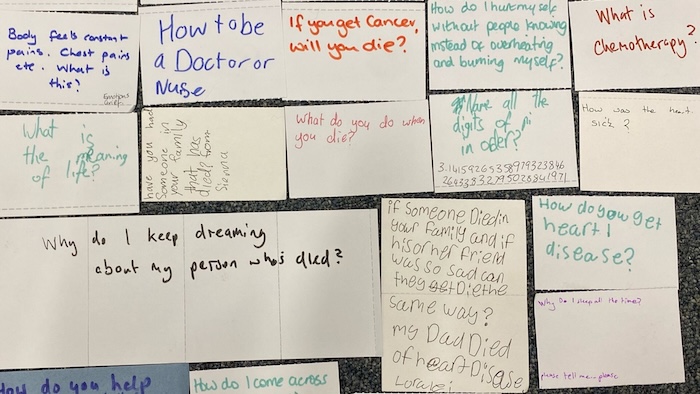

I purchased this provocative piece of clothing from the Order of the Good Death, a group whose stance is simple: “Everyone deserves a healthy relationship with mortality grounded in accurate facts, science, and history.” The group promotes awareness of and advocacy for meaningful and affordable death experiences for “your own death, the death of those you love, the pain of dying, the afterlife (or lack thereof), grief, corpses, bodily decomposition, or all of the above.” As a frontrunner in the international “Death Positive” movement, the Order encourages people to, at the very least, have conversations about death, including informing family and friends about end-of-life wishes. Looking back, I see that an hour-long conversation with my father-in-law could have saved so much of the pain I continue to endure because of his loss.

While I hope to work up the courage to wear my tee in public, perhaps in the meantime I can begin to wear it around the house when making my calendars and to-do lists. With my death planning mostly done, I want to get back to living.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!