— Our funeral practices have a high carbon footprint. Becca Warner explores how she could plan her own more environmentally-friendly burial.

By Becca Warner

Not many of us like talking about death. It’s dark, and sad, and prone to throwing us into an existential spiral. But the uncomfortable truth is that, as someone who cares about the environment, I realised I needed to stop ignoring the reality of it. Once we’re gone, our bodies need somewhere to go – and the ways that we typically burn or bury bodies in the West come at a scary environmental cost.

Most people in the UK (where I’m from) are cremated when they die, and burning bodies isn’t good for the planet. The stats make wince-worthy reading. A typical cremation in the UK is gas-powered, and is estimated to produce 126kg (278lb) CO2 equivalent emissions (CO2e) – about the same as driving from Brighton to Edinburgh. In the US, the average is even higher, at 208kg (459lb) CO2e. It’s perhaps not the most carbon-intensive thing we’ll do in our lives – but when the majority of people in many countries opt to go up in smoke when they die, those emissions quickly add up.

What is CO2e?

CO2 equivalent, or CO2e, is the metric used to quantify the emissions from various greenhouse gases on the basis of their capacity to warm the atmosphere – their global warming potential.

Burying a body isn’t much better. In some countries, the grave is lined with concrete, a carbon intensive material, and the body housed in a resource-heavy wood or steel coffin. Highly toxic embalming fluid, such as formaldehyde, is often used, which leaches into the soil alongside heavy metals that harm ecosystems and pollute the water table. And the coffin alone can be responsible for as much as 46kg (101lb) CO2e, depending on the combination of materials used.

I spend my days attempting to tread lightly on the planet – recycling cereal boxes, taking the bus, choosing tofu over steak. The idea that my death will necessitate one final, poisonous act is hard to stomach. I am resolved to find a more sustainable option. (Listen to the Climate Question’s episode exploring whether we can have a climate-friendly death).

My first port of call is the Natural Death Centre, a charity based in the UK. I pick up the phone and am pleased to find Rosie Inman-Cook on the other end of the line – a chatty, no-nonsense type who is quick to warn me about the dubiousness of many alternative deathcare practices. “There are always companies jumping on the bandwagon, seeing a cash cow, inventing stuff. There’s a lot of coffin producers and funeral packages that will sell you a ‘green thing’ and plant a tree. You have to be careful.”

Her warning brings to mind some “eco urns” I’ve read about. Some are biodegradable, so that buried ashes can be mixed with soil and grow into a tree; others combine ashes with cement so they can form part of an artificial coral reef. These options offer a kind of eco-novelty: what’s a more fitting end for an ocean lover than to rest among the reefs or for a forest fanatic to “transform” into a tree after their death? The only problem is that however sustainable the urn, the ashes deposited in it are the product of carbon-intensive cremation.

So can I avoid my body becoming a billowing cloud of black smoke in the first place?

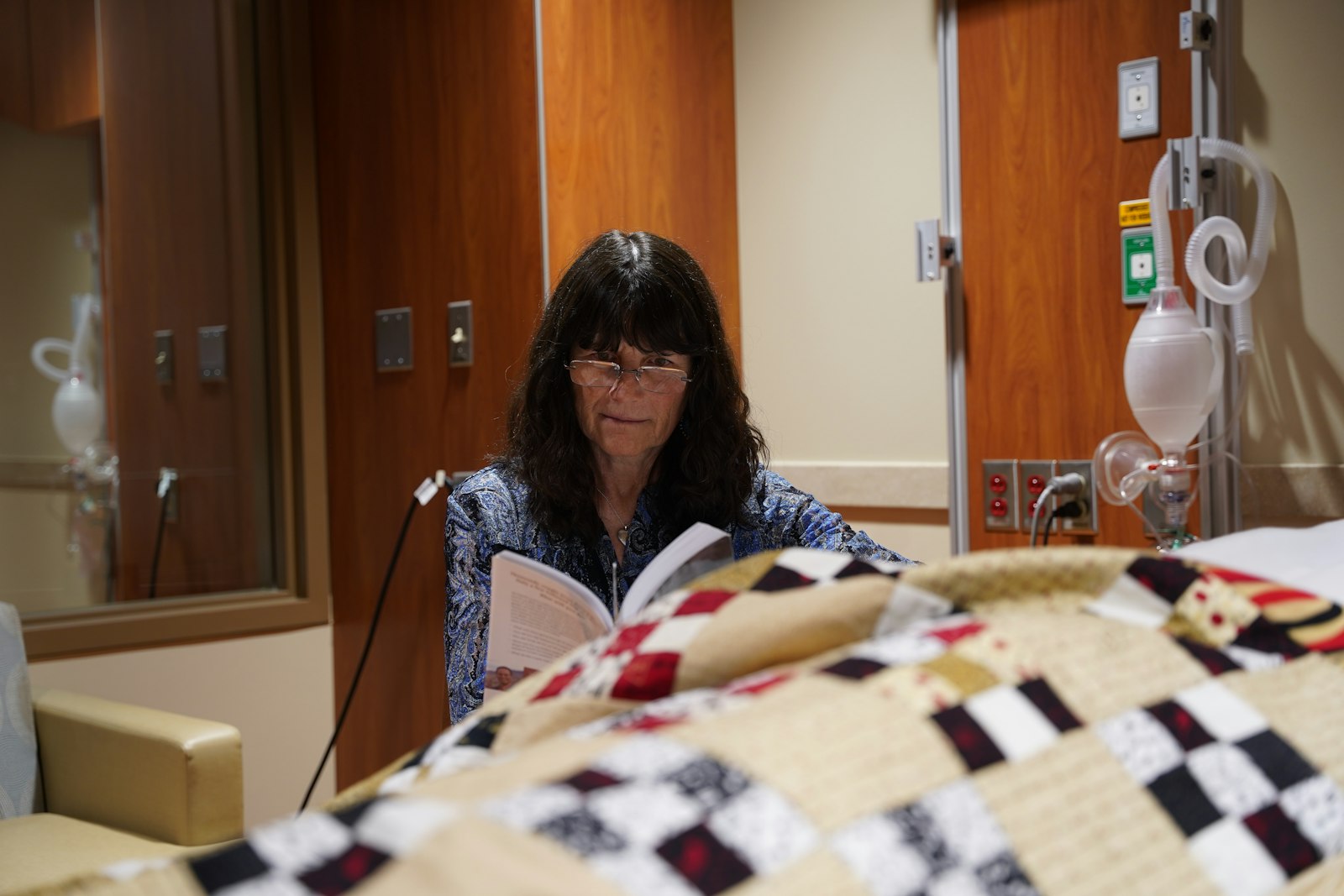

Inman-Cook’s remit is natural burials. This involves burying a body without any barriers to decomposition – no embalming fluids, no plastic liners or metal caskets. All of this means zero CO2 emissions, according to a recent analysis conducted by UK sustainability certification company Planet Mark. The body is buried in a relatively shallow grave, which might be someone’s garden, or, more often, a natural burial site.

Some natural burial sites allow graves to be marked with stones or other simple markers; others are stricter and don’t allow any markings at all. These are woodlands or other wildlife-rich places, often managed in a way that actively supports conservation. “It’s [about] creating green spaces for wildlife, nice places for people to visit, planting new woodland at the same time – and it’s a positive legacy,” Inman-Cook says.

But what of the not-so-natural materials that make their way into the human body – pharmaceuticals, microplastics, heavy metals? They surely don’t belong in the ground. One solution might come in the form of a coffin made of fungi. The Loop Living Cocoon claims to be the world’s first living coffin. It is made of a native, non-invasive species of mushroom mycelium, which is also used to create insulation panels, packaging and furniture. I speak to its inventor, Bob Hendrikx.

“The best thing that we can do is die in the forest and just lay there,” he says. “But one of the problems we’re facing is soil degradation – the quality of the soil is getting poorer and poorer, especially in funeral sites, because there’s a lot of pollution there. The human body is [also] getting more polluting.” Microplastics, for example, have now been found in human blood.

Mycelium has the power to increase soil health and absorb heavy metals that would otherwise leach into groundwater. Some fungi species have been found to break down microplastics, and future research could uncover ways to harness this for human burials.

But based on current research, the real impact of today’s mushroom coffins is difficult to know. I ask Rima Trofimovaite, author of Planet Mark’s report, what the likely benefits of a mushroom coffin are. She says that there is limited data on whether human bodies pollute the ground following a natural burial in a shallow grave. But she says that it is likely that most pollutants are “sorted out at the right level with the right organisms” when only a few feet underground, no extra fungi needed. “I think an option like this is still important,” she says. “We know that natural burial is the least emitting, but not everyone likes being wrapped up in a cotton shroud. People might prefer a mushroom coffin because it has a shape.”

However ecologically sound a natural burial – with or without fungi – might be, land remains precious. In cities in particular, green space for natural woodland burials is at a premium. It was this that prompted young architecture student Katrina Spade to investigate what could be done to make burials in cities less wasteful. Her solution is a logical one: to compost the body in a hexagonal steel vessel, reducing it to a nutrient-dense soil that the family can lay onto their garden.

Sustainabilty on a Shoestring

We currently live in an unsustainable world. While the biggest gains in the fight to curb climate change will come from the decisions made by governments and industries, we can all play our part. In Sustainability on a Shoestring, BBC Future explores how each of us can contribute as individuals to reducing carbon emissions by living more sustainably, without breaking the bank.

Spade launched Recompose, the world’s first human composting facility, in Seattle in 2020. Washington was the first US state legalise human composting the same year, and the practice is now legal in seven US states. Other human composting facilities have sprung up in Colorado and Washington.

Recompose has so far composted around 300 bodies. The process happens over the course of five to seven weeks. Lying in its specialised vessel, the body is surrounded by wood chips, alfalfa and straw. The air is carefully monitored and controlled, to make it a comfortable home for the microbes that help speed up the body’s decomposition. The remains are eventually removed, having transformed into two wheelbarrows-worth of compost. The bones and teeth – which don’t decompose – are removed, broken down mechanically, and added to the compost. Any implants, pacemakers or artificial joints are recycled whenever possible, says Spade.

With no need for energy-intense burning, human composting has a far smaller carbon footprint than cremation. In a lifecycle assessment conducted by Leiden University and Delft University of Technology, using data provided by Recompose, the climate impact of composting a body was found to be a fraction of that of cremation: 28kg (62lb) of CO2e compared to 208kg (459lb) CO2e in the US. When I ask Spade about the production of methane – a particularly harmful greenhouse gas that is released when organic matter rots – she explains that the vessels are aerated to ensure there’s plenty of oxygen. This prevents the anaerobic process that causes rotting, she says.

Turning a human body into soil also reminds us that “we’re not adjacent to nature, we’re part of nature,” Spade says. This shift in our relationship to the natural world is an environmental benefit that’s hard to quantify but is “critical to the plight of the planet”, she says.

Can anyone be composted? I ask Spade this question as I want to know if I’d “qualify” to meet the same end as a banana peel. The answer is, broadly, yes – but not if I’ve died of Ebola, a prion disease (a rare type of transmissible brain disease), or tuberculosis, as these pathogens have not been shown to be broken down by composting, says Spade.

As she describes the process, it strikes me that clothes would presumably not be welcome in the composting vessel. Instead, the remains are shrouded in linen, and families who choose to hold a ceremony can cover them with organic wood chips, straw, flowers, even shredded love letters.

“In one case, a family brought red bell peppers and purple onions that had just ripened in their loved one’s garden – it was so beautiful,” Spade recalls. The body enters a “threshold vessel”, where the Recompose team takes over. They remove the linen shroud but not the flowers and vegetables. I quietly hope that my family would really go for it here. I picture baskets of pine cones, mounds of mushrooms, maybe some of my beloved house plants.

This is all feeling very earthy – but there is another low-carbon option that centres around a different element: water. “Water cremation” (also known as “aquamation”, “alkaline hydrolysis” or “resomation”) is an alternative to traditional cremation, and was the method of choice for Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who helped end apartheid in South Africa. It is another altogether gentler and cleaner affair than cremation, producing just 20kg (44lb) CO2e. “That’s a big difference,” Trofimovaite says. “You slash massive amounts of emissions with resomation compared to flame cremation.”

Approximately 1,500 litres (330 gallons) of water is mixed with potassium hydroxide, and heated to 150C (302°F). In just four hours, the human body is reduced to sterile liquid. More than 20,000 people have been water cremated over the last 12 years, mostly in the US. The UK’s largest funeral provider, Co-op Funeralcare, recently announced that it will introduce the practice later this year.

The speed of water cremation makes it a great budget option. The Co-op anticipate the cost to be comparable to flame cremation – around £1,200 ($1,500) with basic support but no funeral service. Natural burials can be a similar price, but costs are often much higher, depending on the individual burial site. Composting is a lot more pricey at $7,000 (£5,500) – slightly more than the average standard UK burial, which costs £4,794 ($6,107).

I speak to Sandy Sullivan, founder of Resomation – a company that sells water cremation equipment to funeral homes across North America, Ireland and the UK (and plans to in the Netherlands, New Zealand and Australia in the next year). He is patient when I say I’m picturing the process as a kind of melting, and that I’m not sure how I feel about that.

“This is what you end up with,” he says, holding up a large, clear bag filled with a bright white powder. “This is flour, by the way,” he adds quickly. The point is that the final product is dry, ash-like. The flour is a likeness of what is returned to the family, and it comprises only the bones, which have been mechanically crushed (as they are following flame cremation). The soft tissue of the body is broken down in the water and disappears down the pipes to the water treatment plant.

Sullivan’s bag of flour represents the physical takeaway that is so important to many families. It demonstrates what Julie Rugg, director of the University of York’s Cemetery Research Group in the UK, says is central to so much of our thinking about funeral practices.

“In the face of death, we seek consolation. And it’s been really interesting seeing how there’s been a conflict, in some cases, between what is sustainable and what people find consoling,” she says. Bags of bone ash and compost go some way towards overcoming this by offering us something tangible, an anchor for our grief.

As I consider the various options I’ve learned about – melting, mulching, mycellium – I find my thoughts returning to my first conversation with Inman-Cook. I am taken with the simplicity of natural burial, the absence of any bell, whistle, vessel or chamber. I’m pleased to learn that, based on all she has learned during her scientific analysis, Trofimovaite has reached the same conclusion. “I would try to do it as natural as possible,” she tells me. “Natural burials are the most appealing.” But an unmarked natural burial is a perfect example of the conflict Rugg has identified.

Carbon Count

“Somebody says they love the idea of being buried in this beautiful meadow, but they can’t put anything down on the grave,” she says. Rugg describes “guerilla gardening” taking place at one natural burial site, by a family member intent on surreptitiously marking their loved one’s grave with distinctive clovers. “What we’ve got to arrive at is a system which allows us to feel that our loss is special. We’ve got to think about sustainability at scale that still offers consolation.”

The answer, it seems to me, could lie in reimagining what “special” can mean. As Rugg says, in a typical memorial garden “you can’t move for plaques everywhere. We resist the dead disappearing, and actually we find that less consoling than we might think.”

I come away from the conversation with a clear sense that, assuming I’ve avoided going up in a puff of smoke, one of the most helpful things I can do is to refuse to lay claim to any single patch of land at all. I hope my family could find consolation in the knowledge that I’d be happier becoming one with a whole landscape. Why be a tree when I can become a forest?

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!