We are dedicated to helping our patients, but there are limits to what we can do to help.

A clinic patient of mine was dying of pancreatic cancer. He was as orange as a pumpkin and had an implantable morphine pump for pain. He was in palliative care and hospice, and regardless of medications to help alleviate his symptoms, he was miserable.

His suffering was unbearable. He wanted nothing more than to pass away sooner, in peace, and no longer be in pain.

“‘This is not living,’ he told me. ‘I am just waiting to die.’”

— Kristen Fuller, MD

He voluntarily stopped eating and drinking, refused a feeding tube, and eventually developed severe psychosis. I consulted with his medical team members about offering him “death with dignity,” but they were uncomfortable with this.

He passed away on day 12 by starving himself. His loved ones were beyond scarred by this experience.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed the profound tragedy of people dying alone in hospitals, suffering and scared, without the comfort of their loved ones. The pandemic demonstrated modern medicine’s limits in relieving suffering and granting someone peace.

How can we best serve our patients in such situations?

Ways to help patients at the end

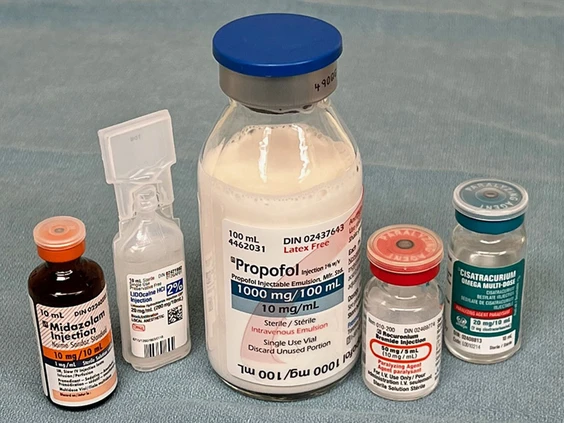

Medical aid in dying—also known as death with dignity—is the voluntary act (for both physician and patient) to help end the suffering of a mentally competent adult patient who is terminally ill with less than a 6-month life expectancy (hospice-eligible). The patient has the right to ask for a prescription medication they can self-ingest to die peacefully.

Individuals who want this end-of-life care option tend to be offended when it’s called “assisted suicide,” because they desperately want to live, but are going to die whether or not they utilize this avenue.

The Journal of Palliative Medicine published peer-reviewed clinical criteria for “physician aid in dying”—not assisted suicide.[1] The term “physician-assisted suicide” is archaic and stigmatizing to physicians and patients who have experienced death with dignity.[2]

In the US, death with dignity or medical aid in dying are explicitly distinguished from euthanasia.

Euthanasia, also called mercy killing, is administering a lethal medication by another human being to an incurably suffering patient.[3]

It may be voluntary (requested by the patient) or involuntary. Euthanasia is illegal in the US, but voluntary euthanasia is legal in Colombia, Belgium, Canada, and Luxembourg, and is decriminalized in the Netherlands.

History and guidelines

Medical aid in dying was first passed as legislation in Washington state in 2008, and has since become available for patients in Washington, DC, California, Colorado, Hawaii, Maine, Montana, New Jersey, Oregon, Vermont, and Washington.

Multiple safeguards are in place to prevent cases of abuse or coercion.

The patient must be deemed competent, two physicians must authorize the medication, and there’s also usually a 15-day waiting period between the first and second doctor’s approval before a medication is authorized.

Suppose the patient chooses to take the medication after authorization. They can ingest the pills at their chosen time, choosing the manner and location of their death—one last act of control in the face of a debilitating illness.

What does the AMA say?

The AMA adopted a neutral position on death with dignity in 2019, affirming for the first time that “physicians can provide medical aid in dying according to the dictates of their conscience without violating their professional obligations.”[4]

The Association stipulated that physicians who participate in medical aid in dying adhere to professional and ethical obligations, as do physicians who decline to participate.

Other well-known national medical associations that have taken a neutral stance on death with dignity by withdrawing their opposition to the practice include the American Academy of Family Physicians, the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, and the American Academy of Neurology.

Empowering patients

According to the Oregon Health Authority, approximately one-third of patients who receive prescription medication to pursue death with dignity in Oregon do not take the medication.[5]

However, they are said to be relieved that they are in control at the end of their life, which helps alleviate some anxiety about potential suffering in their last days. Each patient should be empowered to make end-of-life care decisions based on their unique culture, beliefs, and spiritual values.

“The power should be in the patient’s hands.”

— Kristen Fuller, MD

Hopefully, we can be conduits to give our patients respect, autonomy, and privacy during their last days.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

What an End-of-Life Doula Can Do for You

— Sometimes, you need help navigating your grief and the dying process

Death and dying aren’t always easy subjects. Conversations about your end-of-life desires and the legacy you want to leave behind can be particularly difficult for some individuals, as well as their family and friends.

If you’re diagnosed with a terminal illness, understanding how much time you have left and deciding how you’ll spend it can be difficult to navigate. For friends and family members — especially for young ones who’ve never experienced a death in their family — understanding what happens when someone dies can be confusing and challenging.

When we broach the topic of death, we’re forced to confront our own mortality and come to terms with what will happen to our bodies when we die. But when we face the death of a loved one, we’re confronted with a different set of challenges. Sometimes, we’re dealing with an impending death long before it happens. Other times, death happens swiftly and suddenly in the most unexpected ways.

No matter how someone dies, we each find different ways to grieve the loss of a loved one. Sometimes, we have to handle all the logistics around someone’s funerary services. And then, there are all the things left unfinished in the wake of that person’s death — their hobbies, their dreams, their bills and their responsibilities.

While dying can sometimes be a complicated experience, having help along the way to process your grief and understand what’s happening can make the act of dying more manageable. That’s where having an end-of-life doula can help.

Palliative medicine physician David Harris, MD, and end-of-life doula and social worker Anne O’Neill, LSW, CDP, explain how end-of-life doulas work together with palliative care and hospice teams, and exactly what you can expect when hiring an end-of-life doula.

What is a death doula?

Birth doulas and death doulas function like two sides of the same coin. A birth doula is a trained professional that assists someone before, during and after childbirth. They work alongside your healthcare team to provide emotional and physical support, education and guidance to make sure you have a positive birthing experience.

Similarly, a death doula — also known as an end-of-life doula, end-of-life coach, death midwife or death coach — assists a dying person and their loved ones before, during and after death. An end-of-life doula provides emotional and physical support, education about the dying process, preparation for what’s to come and guidance while you’re grieving.

“A doula wants to do as much as they possibly can to help facilitate what the person and their family need,” says O’Neill. “Doulas make sure the threads are connected between the dying person and the important people in their lives, including their hospice team.”

End-of-life doulas aren’t licensed to provide any medical assistance, but they may advocate for the dying person’s wishes and needs while working together with healthcare providers.

“There is value in having an interdisciplinary team, with the idea that different fields have different things they bring to the table,” notes Dr. Harris. “The best way to give great care to someone is to involve different viewpoints, different levels of expertise and different types of expertise. End-of-life doulas and religious leaders both fall into that framework.”

In recent years, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic and the surge of related deaths worldwide, there’s been an increased interest in hiring end-of-life doulas to help those who were dying and those who were grieving. There’s also been an increased interest in people wanting to become licensed as end-of-life doulas.

“For many people who are approaching the end of life, being prepared and having everything in place for when they do die is a very important thing. They don’t want their families to be scrambling, and they have certain ideas about what they want their funeral to look like,” explains Dr. Harris.

“Usually, in palliative care or hospice, we give them the space and a listening person to help them plan out what they really want. For many, it’s not as much about finding a funeral home or finding resources as it is just a hard thing to talk about.”

And in many ways, the core function of an end-of-life doula is to be present and listen to the needs of the person who’s dying and the needs of those around them who are grieving.

“We don’t die twice. We only get one chance to do this,” says O’Neill. “When you’re bringing in a doula, you’re bringing in a wide range of experience and a real desire to want to be there with that person and to make it as good of an experience as it can be.”

What exactly does an end-of-life doula do?

Each dying person’s needs are unique to their specific situation, but the services offered by an end-of-life doula could include a mix of the following:

- Providing the opportunity to talk openly and honestly about the dying process.

- Alleviating the anxiety, guilt and shame often associated with death and dying.

- Developing a plan for how the person’s environment looks, feels, sounds and smells.

- Coordinating with family and friends to evaluate visitation.

- Overseeing 24/7 care alongside healthcare providers like hospice and palliative care.

- Providing education and guidance related to other medical services like do-not-resuscitate orders and healthcare power of attorneys.

- Creating guided meditations and rituals specific to a person’s religious faith or spirituality.

- Sitting vigil with a person as they near their final moments.

- Assisting with obituaries and planning funeral services.

- Providing supplemental grief counseling and companionship after someone has died.

- Finding creative ways to honor the person after they’ve died, which can include the person who’s dying as a part of that process and exploring that person’s life and legacy.

“Our goal is to provide the kind of support people need so that families aren’t exhausted. We want families to have a chance to rest and we want to ensure that people who are dying are not unsafe at home,” O’Neill adds.

Part of that process is making sure the person who’s dying is aware of what’s happening and, if they’re able or they desire it, to give them the space to confront their own grief and be an active participant in their dying process.

“A dying person is grieving their losses, too. They’ll never see their partners again. They’ll never do the things they love again. So, the doula allows a dying person to express their losses,” says O’Neill.

Along the way, an end-of-life doula may help with what’s referred to as “legacy work,” a process O’Neill says is about exploring the most meaningful moments of someone’s life and finding ways to pass on their legacy. Sometimes, this looks like putting together a scrapbook of memories. Other times, it’s about making those phone calls and writing those letters to long-lost friends or siblings and finding closure in other ways.

“Doulas can help facilitate those conversations to make sure they tie up those loose ends and they’re able to say what they want to say before it’s too late,” she explains. “I had one gentleman who always wore flannel shirts his whole life. He and I cut the buttons off of his flannel shirts and made bracelets for his granddaughters so that they would have those to remember him after he died.”

And end-of-life doulas can extend their services to those loved ones who are grieving by providing education and resources along the way. Sometimes, that means a doula may have to call the funeral home to announce the death of the person who died and make an appointment for the funeral. Other times, a doula may just be on standby should the family need their support during the final hours of a person’s life and in the weeks or months after they’ve died.

“Our hearts have to fill back up again after such a loss,” notes O’Neill. “As doulas, we’ve come to know these families, so we are able to give them what support they need afterward. We don’t just close the book and say, ‘On to the next one.’”

What’s the difference between a death doula and hospice?

End-of-life doulas are similar to hospice care in that both offer counseling, spiritual support and other nonmedical services to help a dying person and their loved ones during their final days. The medical piece is what sets hospice care and end-of-life doulas apart because doulas are typically not licensed to provide any hands-on medical assistance. That said, doulas are fast becoming an integrated part of hospice care teams. If your hospice care team doesn’t have an in-house doula, if you decide to hire one, the hospice care team should work with them throughout the dying process.

“An end-of-life doula’s approach to care is very consistent with hospice care and they’re very synergistic,” says Dr. Harris. “Where end-of-life doulas excel seems to be advocating for people who are dying, planning and having some of those crucial conversations.

“The medical piece is just a small part of somebody’s end-of-life experience and we have to acknowledge, as healthcare providers, that sometimes the medical pieces aren’t the most important pieces. Sometimes, it’s connecting, from one human to another.”

What type of training or certification does a death doula have?

There are a variety of accreditations available to those interested in becoming an end-of-life doula. Although there aren’t universally recognized requirements for becoming an end-of-life doula yet, organizations like the International End-Of-Life Doula Association and the National End-Of-Life Doula Alliance offer training and certification requirements that include:

- Reading required materials.

- Completing a work-study or class.

- Participating in a multiday training program or workshop.

- Obtaining recommendations from healthcare providers and people they’ve assisted.

- Following a strict code of ethics.

“Individuals and their families are very vulnerable when they’re at the end of their lives, so that ethical piece really needs to be there and needs to be pronounced,” stresses O’Neill.

Should you hire a death doula?

The decision to hire an end-of-life doula is a very personal decision, one that should be discussed with you and your family in the same manner of understanding and respect that any other end-of-life decisions should be discussed.

“It’s not easy being cared for. When you see your doctors, you’re expected to sort of be able to clarify and explain exactly what’s going on physically, emotionally, spiritually. At the same time, you’re not feeling well. So, that’s a really hard thing to do,” states Dr. Harris.

“Having somebody like a death doula who has experience taking care of people at the end of their lives and who has the time to sit and be with that person and help them figure out what’s going on can be really valuable.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Preparing Jewish bodies for burial, an artist finds inspiration

‘I could have painted landscapes,’ says Karen Benioff Friedman. Instead, she’s portraying the rituals around death.

By Stewart Ain

When a Berkeley rabbi in 2004 announced that he wanted to form a chevra kadisha, Hebrew for a group that cares for the dead before burial, an artist in his congregation signed herself up.

Karen Benioff Friedman had a mostly secular upbringing, and hadn’t known much about Jewish burial societies, but she knew she wanted to be a part of one.

“What I found compelling is the idea that we never leave the dead alone,” she said.

1 / 9

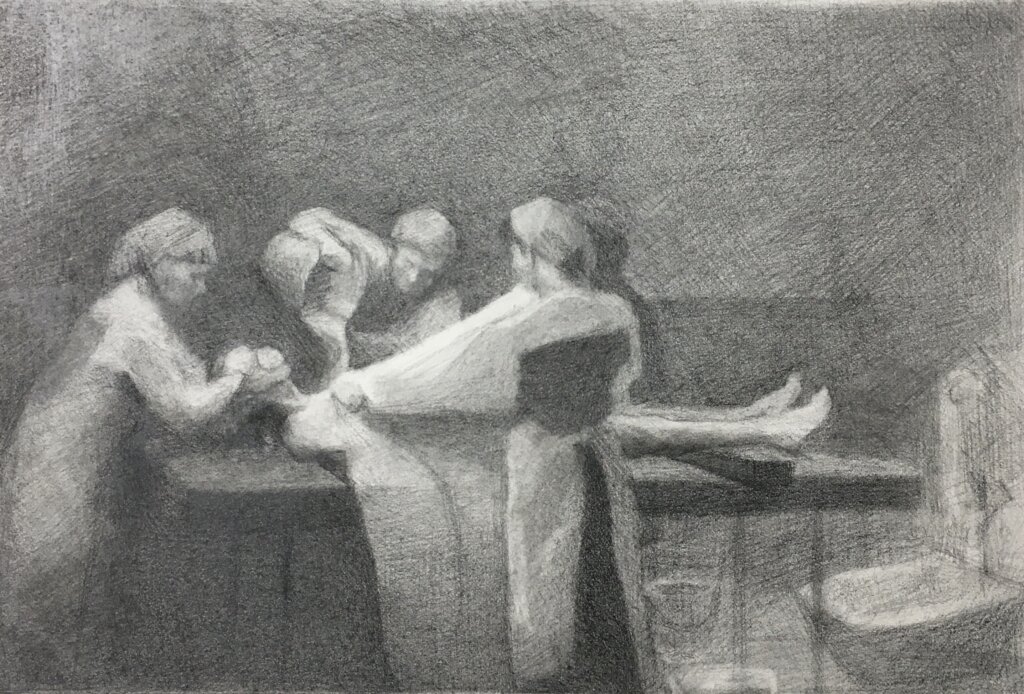

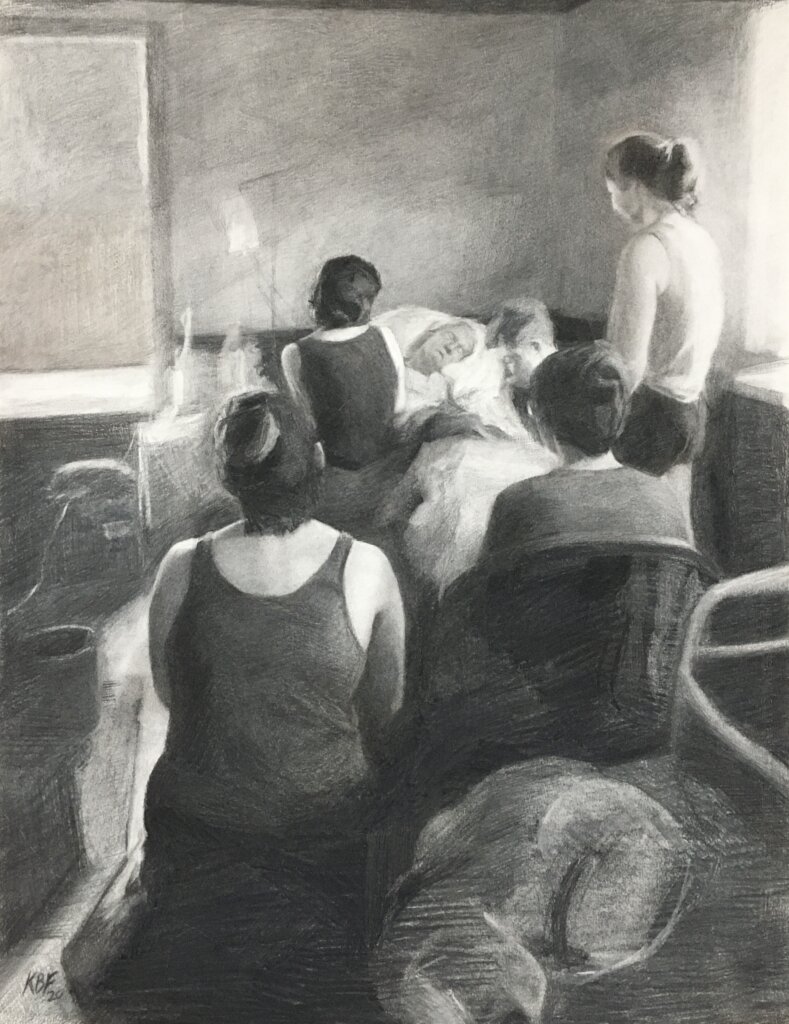

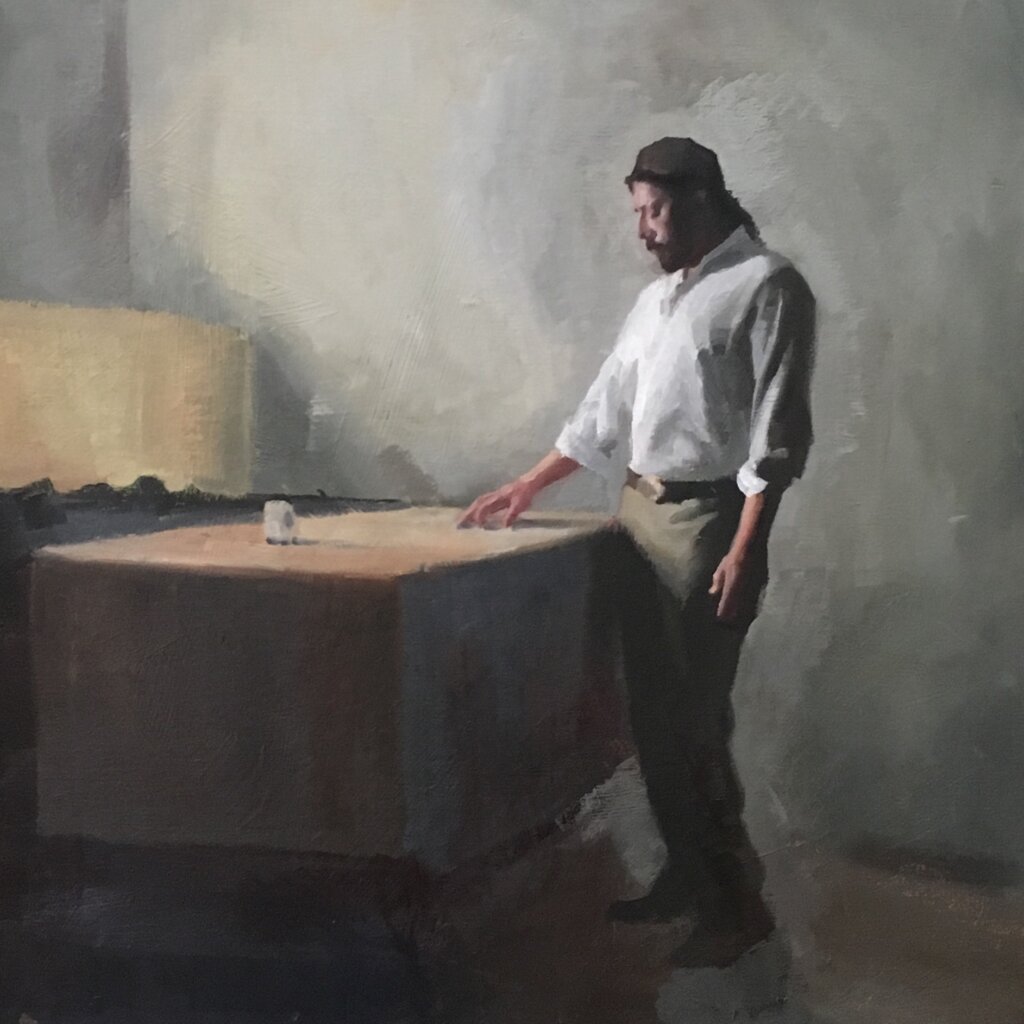

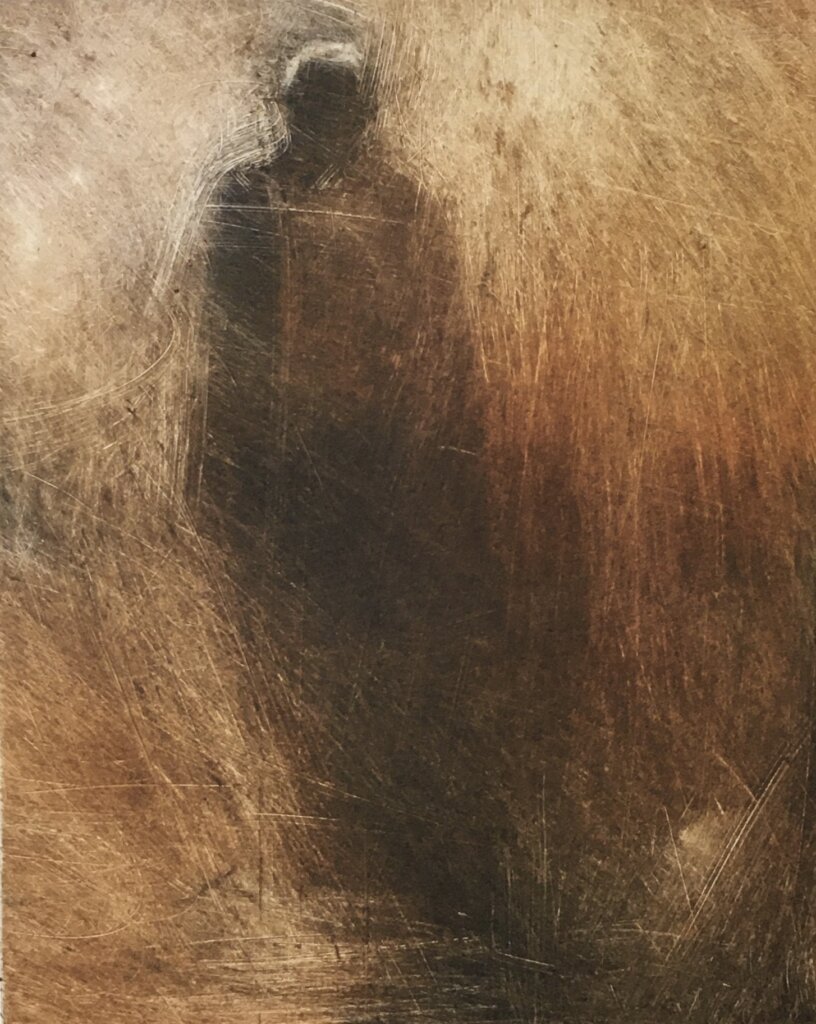

Ten years later, while Friedman was studying human anatomy and classical realism at an Oakland art school, she learned of 18th century paintings of Prague’s chevra kadisha. They depicted tahara, the rituals of the burial society.

2 / 9

As part of these rituals, bodies are placed in a white shroud before they are lowered into a casket. Coincidentally, Friedman had been painting images of shrouded figures. Seeing the Prague paintings made her think that tahara could be her subject too.

3 / 9

“I could have painted landscapes or pets, but this is what really moved me,” said Friedman.

4 / 9

Since then, Friedman, now 59, has drawn, painted and etched more than 150 images of tahara, each a window into a ritual so private that many Jews have little idea what it looks like. Those who perform tahara wash the body, and sit by it through the night, reciting prayers and psalms.

In her paintings, gauzy figures, some enveloped in light, attend lovingly to the dead, cradling their heads and pouring water over their bodies. The mood is somber, despite the daubs of bright blue she often uses for the aprons of the women of the chevra kadisha.

5 / 9

Tahara calls for men to care for men and women for women, so Friedman’s subjects are mostly female, because, she said, that is what she knows from her own participation.

Respecting tahara, which means “purification,” Friedman would never try to draw or take photographs of the deceased. But she didn’t work solely from memory either. She hired models to impersonate both the living and the dead. One model did a “pretend tahara while another pretended to be a body that was dressed in a shroud,” she said. She worked from the photographs she took of them.

6 / 9

Friedman paints in oils and makes monotypes, a form of printmaking. All her drawings are in charcoal.

Many of her works depict angels. “One of the main pieces of liturgy we talk about is the one about the angels of mercy who embrace the metah — the female body,” Friedman said. “Angels come up a lot, including standing outside the gates of heaven. I love the concept of the angels.”

7 / 9

Ultimately, she said, she wants her works to teach about the mostly hidden work of the chevra kadisha, and its commitment to respect the dead, no matter who has died.

8 / 9

“We are all equal in death,” she said. “We all wear the same thing and are buried the same.”

9 / 9

An exhibit of Friedman’s work will open on Feb. 5 at San Francisco’s Sinai Memorial Chapel and run through March 19.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

The toughest conversation

— Talking end of life with patients

I saw my first code during my third year of medical school. A day later, I called my mom to discuss her last wishes if something tragic were to happen to her.

I did not want her to be that patient on the gurney being violently coded if that was against her wish. It took a few years of coaxing her into having these tough conversations with me, and after enough coercing (and having to deal with a few hair-raising medical issues), she told me exactly what she wanted to do when the time came.

I regularly try to talk about this with patients, even if they give me pushback, as I firmly believe that every person should have the power to make an educated decision on what they want to be done at the end of their life.

Despite our regular proximity to death, many physicians may lack the necessary skills to have direct, detailed conversations about code status, long-term prognosis, quality of life, and end-of-life care.

The last thing we want is for our patients to have to make these very emotional and difficult decisions in the last few months—or even minutes—of their lives. Or for their family members to be forced to guess their loved one’s end-of-life wishes after they’ve become incapacitated. But we can help them prepare for that time—provided we know how to do so.

They don’t teach us about death in medical school

During my medical school and residency, we didn’t spend much time discussing death, having end-of-life conversations with patients and families, how to manage pain or anxiety during the dying process, or the intricate differences between hospice and palliative care.

Nobody taught us how to approach or use advance directives, or when to discuss them with patients. Such terms came up in conversation and during rounds, but there was no teaching method or structured learning objective—or even conversations about them.

We learned how to have end-of-life family meetings while watching senior residents, whose styles and conversational skills were all over the map. Death was not a natural, omnipresent, physiological process but rather the unspoken consequence if we did our jobs wrong—almost like a failure.

Becoming comfortable with death

“Death is a normal part of life. Everyone dies and deserves to die with dignity, with the choice of how they take their last breaths.”

— Kristen Fuller, MD

Luckily, in my final year of residency, I had the privilege (after a lot of kicking and screaming) of taking three important elective rotations: palliative care, hospice, and pain management and rehabilitation.

During these months, I learned how to be comfortable with death and dying, appropriately manage pain in all its different forms, have difficult conversations with patients and families about these topics, and give myself grace and compassion when a patient dies.

These skill sets have tremendously helped me in my professional life—as well as in my personal life, as I am often the one having the difficult conversations on these issues with my family members.

Taking control

A Kaiser Family Foundation study reported that only 56% of adult Americans had a serious conversation about healthcare preferences, 27% wrote down their preferences, and just 11% discussed them with a healthcare professional.[1]

The most powerful thing patients and families can do to take control of their healthcare is to think through what’s most important to them if they become seriously ill. They should also identify a person they trust to represent them if they can’t speak for themselves.

It’s never too early to raise the topic

“I always encourage physicians and family members to ask questions about end-of-life care early on, as it’s never too soon to start talking about it—but there is a point where it may be too late.”

— Kristen Fuller, MD

During office visits, try to discuss code status and advance directives with the patient, and encourage family members to talk about it with each other.

Before asking these questions, you may want to discuss why you’re having this conversation. Perhaps you can offer a professional or personal experience you had with death when a patient or family member didn’t have any decision-making powers.

“I often tell patients about my first experience as a medical school student witnessing a code.”

— Kristen Fuller, MD

Here are some possible conversation starters:

- What is important in your life? How would you like to be remembered?

- What experiences have you had so far with death? What do you think death means?

- What will happen when you die? Do you need to make any plans or choices now?

How to discuss end-of-life care

Choose a quiet, comfortable, private space to meet without interruptions (turn off your electronics). Ask your patient what they know about their condition and its prognosis so you can better understand their knowledge and mindset. The goal is for the patient to lead the conversation and tell you what they want to do.

If there are discrepancies between what you and the patient know about their situation, it’s your job to tell them the truth. Use plain language, speak slowly and clearly, and make sure they can hear and understand you. Then give them a few moments to process this information before asking if they have any questions.

Determine what your patient wants in the last years, months, or weeks of their life. How do they wish to take their last breaths? How would they like to spend their time? Do they want to be coded when their heart stops? Do they want to be readmitted to the hospital if their condition worsens? Would they want palliative or hospice care?

“It’s our job to learn and document the patient’s specific wishes. In doing so, we must be honest and educate the patient on the differences between hospice and palliative care.”

— Kristen Fuller, MD

Focus on realistic goals

An author writing in Family Practice Management provided insight on how to guide patients’ expectations about the end of life.[2]

“Redirecting the patient’s focus from ‘cure’ to a more reasonable goal, such as living long enough to complete certain tasks (healing relationships or witnessing certain events such as a wedding or birth of a grandchild) can be helpful,” the author wrote. “Even a pain-free death could be a goal.”

The author added that “it is possible to have both qualities of life and quantity of life,” as research showed that patients who receive hospice care live longer than those who pursue aggressive treatment.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

8 Caring Sympathy Messages

— What To Say When There Are No Words

Words of kindness can have a powerful impact.

When it comes to death and grief, finding the right words to express the deepest sympathy can be difficult. Loss is a natural part of life, but it often leaves us feeling adrift, unsure, and afraid of saying the wrong thing to a person going through an immensely difficult time. The truth is that every person responds to loss differently. While some grieve in private, others prefer the physical presence of friends and loved ones. Whatever the case, sending a sympathy card (even if the words aren’t perfect) to let them know they’re on your mind is important. Below are sympathy messages and words of comfort to offer in a time of need.

Condolence Messages To Write in a Sympathy Card

There are several important things to keep in mind when writing a sympathy note. Two of these are the recipient and the circumstances. For some, the right approach is a message that will make them smile (or even laugh), and provide a brief respite from their grieving process. For others, a spiritual quote or condolence can show solidarity at a sad time that’s often accompanied by loneliness and isolation. Personalization is important, so be sure to customize your sympathy card messages for a family member or close friend according to their situation and your relationship to them. Here are ideas to get you started.

1. I’m So Sorry for Your Loss

When you’re just not sure what to say, don’t be afraid to say something simple, like “I’m sorry for your loss” or “I’m thinking of you in this heartbreaking time.” Writing this in your sympathy card is the clearest way to show love and support. Don’t avoid sending condolences because you’re worried about coming up with the perfect words. (Really, the only words to avoid are “I know how you feel,” which centers you instead of focusing all attention and support on the grieving person.) “I’m so sorry for your loss” can be an opening that allows your friend to share their sadness, or a simple phrase that signals caring thoughts and heartfelt sympathy.

2. I Remember When

One way to add something special to a condolence card is to share happy memories of the person who has passed. This may be a memory of a time they did or said something light and humorous, which can help to give the grieving family some joy on a difficult day. It may also be a memory of a lesson or special message they passed down to your family, like encouragement to pursue a project or support during a difficult time of your own. Memories are incredibly personal, but they also show the family that their loved one had a positive influence on people and will be well-remembered by many.

3. What an Amazing Person

There are other ways — apart from or in addition to sharing a memory — to pay homage to the person who has passed. Were they particularly caring or loving? Did they always bake something special to welcome newcomers to the office or the neighborhood? Could they make everyone laugh? Consider the impact the loved one had on those around them. By referencing specific traits or behaviors, you’re telling the grieving family that you saw the gifts their loved one shared with the world, and that you appreciated them for it. Doing this shows the aggrieved that the legacy of their loved one will live on.

4. A Spiritual Reference

For many, spiritual references are a useful way to navigate loss, especially in initial stages of grief. It’s important, however, to respect the grieving person’s faith — or lack thereof — before referencing God. Religion and spirituality are deeply personal, and referencing them may not always be appropriate. When it is appropriate, consider quoting spiritual texts or beloved hymns. Avoid messages that suggest the loss is part of a larger plan — for example, “Everything happens for a reason,” or “God makes no mistakes” — as these diminish the loss by implying that it’s for a higher purpose. Instead, reference spirituality and messages of peace and love in a way that supports the grieving family by acknowledging the depth of their loss.

5. Sending Love to Your Family in a Time of Sorrow

If you didn’t know the individual who passed, but you do know members of the family, consider writing a condolence card to the grieving person rather than in memory of the deceased. This may reference their influence, such as how they raised such wonderful children, but you can avoid speaking of the deceased person entirely if you don’t feel comfortable. Simply writing heartfelt condolences to the grieving family of the deceased is often enough to show that you care without overstepping.

6. A Poem or Quote for Comfort in a Challenging Time

We don’t always have to find the perfect words ourselves. Loss is a universal experience and has been written about and spoken of in many ways throughout generations. It may be useful to share a quote or a few lines of a poem that you think your loved one will appreciate and perhaps find peace in. When it comes to poems and quotes about loss, you can tailor the writing to the specific individual you’re sharing it with. In some circumstances, it may have religious or spiritual elements. In others, it may be humorous or very serious. If the deceased or someone in the family had a particular love for one writer or singer, it might be special to share a line from them as an homage. Taking the time to pick out a quote they will really appreciate will show the family or your loved one just how much you care.

7. They Left an Impact and Fond Memories

After a loss, we often grieve the missed opportunities and moments our loved one could have shared with us before their passing. Speaking to their impact can ameliorate some of that pain. This could mean referencing the wonderful way they raised their children, speaking to their community fundraising, or sharing a time they helped you navigate a challenge. Knowing their loved one leaves a lasting legacy behind can bring great comfort to the deceased family.

8. A Promise of Help

While sympathy messages and deepest condolences are a wonderful way to support a family or coworker emotionally, logistical needs must also be met. Of all the gestures, tokens, and gift ideas, availing yourself to provide a service during a time of loss is always appreciated. This is especially true if the grieving family has elderly relatives or small children. A promise of help should be intentional and specific so that there is no undue burden on the family to pick up the phone and ask. Rather, you want to give the family the tools and resources they need to care for themselves during loss. That may be gift cards to local restaurants or maid services for the home, or even babysitting support so that they can make arrangements. Taking a few simple tasks off their mind can make a big difference.

Meaningful Messages and Sincere Condolences

When it comes to words of sympathy, there are many ways to share love and comfort at a hard time. The simple act of sending a sympathy card is a welcome show of support for the grieving family.

Depending on your relationship with the deceased and their family, you can further personalize your sympathy message by sharing loving memories, messages of love and comfort, and even quotes or song lyrics. Another way to show up for loved ones during times of loss is with the offer of support and help. Just be sure to take care of the planning so that your offer doesn’t add to their burden. Loss is never easy, but family, friends, and the right words can help us to navigate loss.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

What We Know About Treating Extreme Grief With Psychedelics

— In his new memoir, Prince Harry talks about taking psychedelics to deal with the ongoing pain over the death of his mother. Here’s what we know and don’t know about their effectiveness.

By Dana G. Smith

Prince Harry and Meghan Markle have been remarkably transparent about their psychological struggles. In a documentary about mental health that he filmed with Oprah Winfrey in 2021, Harry included a video of himself undergoing E.M.D.R., or eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy, which helps people with post-traumatic stress disorder cope with triggering memories. Ms. Markle has spoken candidly about experiencing depression and suicidal thoughts.

Harry’s new memoir, “Spare,” is no different, including raw and sometimes shocking details about his battles with mental illness. At the center of many of these experiences is his grief and trauma over the death in 1997 of his mother, Princess Diana, when he was 12 years old.

In the book, he described trying both traditional and unconventional ways to cope with his pain and that using psychedelics was particularly helpful. After one therapist suggested that he suffered from PTSD, Harry started to use mushrooms and ayahuasca “therapeutically, medicinally.” (He had previously experimented with psychedelics recreationally.) “They didn’t simply allow me to escape reality for a while, they let me redefine reality,” he wrote.

Psychedelic therapy has experienced a groundswell of enthusiasm over the past decade as research mounts showing the mind-altering drugs can be useful for treating depression and other mental health disorders. (The therapy is still illegal in most places and is primarily done in underground sessions, abroad or through clinical trials.) However, there is scant evidence about whether psilocybin — the psychoactive ingredient in hallucinogenic mushrooms — and ayahuasca might be helpful for processing grief and trauma specifically.

Dr. Joshua Woolley, director of the Translational Psychedelic Research Program at the University of California, San Francisco, is optimistic about the drugs’ potential. “Can psychedelics help with the experience of grief? I would say probably yes,” he said.

But other experts are less bullish on the idea of using them for trauma. “The actual evidence is really lacking,” said Dr. Shaili Jain, a PTSD specialist at Stanford University and author of “The Unspeakable Mind.” “It’s very early, and we still don’t know the long-term side effects. We are not there yet.”

Grief Versus Prolonged Grief

Grief is not a mental illness; it is a normal human experience that comes after the loss of a loved one. Sadness, anger and disbelief that the person is dead — something that Harry described in his book — are all typical responses to the profound pain of death and can last for months or years. However, if the grief has not improved at all after a year and is affecting a person’s ability to function, a diagnosis of prolonged grief, sometimes called complicated grief, might be warranted.

“What we see with prolonged grief is that the grief becomes very entrenched, that things look the same for this person today as they did the day after” the death, said Mary-Frances O’Connor, an associate professor of psychology at the University of Arizona and author of “The Grieving Brain.” “For a person who’s adapting more typically, a year after a loss, they’re still going to have sadness. They’re still going to miss the person who’s gone. But you can see this trajectory of change where they have started to restore a life that feels meaningful to them.”

People with prolonged grief may feel that life has lost its meaning or that a part of themselves has also died; they might have intense emotional pain or feel complete psychological numbness. Harry does not say in his book whether he was ever diagnosed with prolonged grief, but he does describe some of these emotions, and symptoms of PTSD and prolonged grief often overlap. About 10 percent of people mourning a loved one will develop prolonged grief, and the risk is higher if the death happened suddenly or traumatically.

Treatment for prolonged grief often involves cognitive behavioral therapy to help people start to move on and engage in meaningful activities again while they continue to cope with the grief. “It’s not about taking grief away,” Dr. O’Connor said. “It’s about learning how to live with the fact that you are a person who has waves of grief now.”

Using Psychedelics for Grief

Scientists think that psychedelics work in two ways: through their chemical effects on the brain and the subjective experiences a person has while on the drugs. For many people, psychedelics act like “a very intense, fast psychotherapy,” Dr. Woolley said.

Psychedelics “have this potential to induce these transpersonal states of consciousness where people might feel like they are connected” to the deceased relative or friend, added Greg Fonzo, co-director of the Center for Psychedelic Research and Therapy at Dell Medical School, University of Texas at Austin. “That might allow people to move past some of the stuckness that occurs when they’re in this phase of grief.”

In the brain, scientists think that psychedelics induce a “plastic state,” helping to rapidly form new connections between cells. Those new connections may be behind the insights and reprocessing that people can experience when they use the drugs in a therapeutic setting.

There are very few published studies focusing on psychedelics’ effect on people experiencing prolonged grief. In one of the few relevant trials, Dr. Woolley looked at whether psilocybin, combined with group therapy, could help older, long-term AIDS survivors process their depression and survivor’s guilt surrounding their diagnosis, as well as the loss of friends and family to AIDS. The 2020 study, which included just 18 men, assessed the participants’ levels of demoralization — a therapeutic term for an existential sense of hopelessness and loss of meaning in life. Most of the participants had experienced profound grief and trauma because of the AIDS epidemic; on average, the participants had lost 17 loved ones to the disease.

After one psychedelic therapy session, nearly 90 percent of the men experienced a reduction in demoralization, and many saw a decrease in symptoms of PTSD and complicated grief. In a follow-up paper describing the men’s subjective experiences, the researchers wrote that psilocybin was “a catalyst for reconstructing their identities from rigidly centered on their past traumas to more flexible and growth-oriented life narratives.”

“The people in our study often talked about feeling stuck and detached from people around them and not able to move forward,” Dr. Woolley said. The psilocybin “did seem to help them move forward, to become unstuck and start being more engaged in life.”

Another study published in 2020 by researchers in Spain found that 39 bereaved adults who took part in ayahuasca ceremonies at a retreat center in Peru reported a decrease in the severity of their grief, and those benefits lasted for at least a year. The researchers wrote that people using ayahuasca to process their grief “described emotional confrontations with the reality of the death, the reviewing of biographical memories, and a re-encounter with the deceased.”

While these results are promising, both studies were small and neither included a control arm to compare the effects of the psychedelics against a placebo or another medication. The majority of participants in the ayahuasca study also reported that they expected to benefit from the experience, which may have had an impact on the results.

There is stronger evidence that psilocybin can be useful in treating depression, including in trials comparing the drugs’ efficacy to standard antidepressant medications. Similarly, M.D.M.A, which is sometimes classified as a psychedelic, has been shown to be effective at treating PTSD. Some researchers think that because prolonged grief has many similarities with depression and PTSD, psychedelics could be useful for treating it too.

Dr. O’Connor said that given how scientists think psychedelics work in the brain to treat depression, it’s conceivable that the drugs could also be helpful for people with prolonged grief. However, she cautioned against using the drugs to cope with grief that had not been diagnosed as prolonged or complicated.

“I would not say that it is appropriate to intervene with something as mind-altering, as dramatic, as psychedelic therapy if a person is, in fact, healing in the way that we would expect them to,” Dr. O’Connor said. “Meaning, I would worry that you could do more harm than good and that it just may not be necessary.”

The experts also emphasized that experimenting with the drugs recreationally is not the same as using them in a controlled therapeutic environment. After trying psychedelics in both settings, Prince Harry echoed this sentiment. In an interview with 60 Minutes, he said that he “would never recommend people to do this recreationally,” but that in the right setting the drugs worked “as a medicine” to help him process his grief and trauma.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Death Cafes Spread Rapidly Around the World

Jon Underwood held the first Death Cafe in 2011 at his East London home. This single event lit a movement that spread quickly to 82 countries, hosting over 15,000 Death Cafes on nearly every continent by 2023. What is a Death Cafe, and why is the world so interested?

- Death Cafes are informal, social events where people talk freely about death without any agenda, objective, or theme.

- Anyone can host a Death Cafe if they sign up to follow the Death Cafe guide.

- Death Cafes are spreading rapidly around the world and attracting diverse attendees.

- Many global and cultural factors combine to cause such rapid growth of Death Cafes.

- Studies suggest talking about death in a safe, non-judgmental atmosphere is healthy.

What is a Death Cafe?

A Death Cafe is an informal social event where people, often strangers, get together to talk freely about death over cake and tea. As stated by the Death Cafe franchise, the mission is “to increase awareness of death with a view to helping people make the most of their (finite) lives.”

A host guides the gathering’s discussion to ensure there is no agenda, objective, or theme. Instead, the goal is to provide a free-flowing and open conversation about any aspect of death.

Technically, Death Cafe is a non-profit social franchise, meaning the Death Cafe founders oversee the movement’s branding, process, and mission. To use the name “Death Cafe,” one must register with the organization to plan and host a gathering.

A registered host must follow four Death Cafe principles as quoted from their website:

- With no intention of leading participants to any conclusion, product, or course of action.

- As an open, respectful, and confidential space where people can express their views safely.

- On a not-for-profit basis.

- Alongside refreshing drinks and nourishing food — and cake.

What a Death Cafe is not

A Death Cafe is a grassroots event anyone can host. Since it’s a simple, free-flowing conversation, professional credentials to host aren’t required.

Death Cafes are not grief support groups or counseling sessions. They do not meet to promote the agenda of any ideology or end-of-life organization. Hosting a theme-related gathering, inviting guest speakers, or handing out educational materials is against the Death Cafe guide.

Hosts allow people to talk about their beliefs about death but do not allow participants to press others to agree. Instead, the conversation is a curious exploration about dying to help people live now and gain greater peace.

Death Cafes attract diverse people

Because Death Cafes touch a vulnerable place in the human heart, the gathering reaches beyond race, culture, and nationality.

In 2020, a team of researchers from the University of Glasglow published a study on the global spread of Death Cafes. They interviewed 49 Death Cafe hosts in 34 countries to explore how and why the event spread globally.

The team’s study confirmed the spread of the Death Cafe movement from the UK to North America, Europe, Asia, South America, and Africa, providing evidence that the movement attracts diverse attendees.

The café hosts reported a wide range of participant ages. Attendees varied from teenagers to 80-year-olds, sometimes in one group, while the hosts’ ages ranged from 20-70.

In gatherings of 2-70 people, the participants were primarily women, but men also found the topic engaging.

The location of Death Cafes was diverse, too. According to the study, the cafes “took place in pubs, function rooms, leisure centers, people’s homes, and even cemeteries.”

Why are Death Cafes growing so fast?

Like birth, death is a universal human experience. However, unfortunately, our ideas about death are heavily cloaked in personal fears and cultural beliefs, creating taboos and mysteries we’re afraid to question or discuss.

Beyond personal beliefs, today’s medical industry treats death as a medical event rather than a sacred human experience. In addition, many communities now leave deathcare — the care of the human body after death — to medical and funeral professionals behind closed doors.

When you add these factors to the COVID-19 pandemic, a large baby boomer generation, rising chronic illness rates, and the relentless mental health crisis, it’s not surprising curiosity about death grows worldwide.

At the same time, cultural movements like death positivity, palliative care, and green burial options increase the safety of talking about death. More people today question their spiritual traditions, too, leaving them to wonder more about the dying process and the afterlife.

Medical assistance in dying (MAID) is growing globally as countries like Canada loosen their rules. More people are thinking about medically-assisted death — also called death with dignity and physician-assisted suicide — even if they’re not near the end-of-their lives.

The compounding effect of all these factors leaves a gaping human need to talk about death and dying. That energy for discussion and connection drives the growth of Death Cafes worldwide.

Talking about death is healthy

As death awareness grows globally, so does the science. Experts and researchers today argue that talking about death is good for you. It helps you clarify your beliefs on quality of life both now — even if you’re young — and when you’re dying.

However, talking about death isn’t easy. People’s desire to face the subject varies widely. Death Cafes seem to help those eager to talk about it as well as those afraid of the discussion.

In the University of Glasgow’s study, hosts reported that “strangers are just opening up,” and conversations happen without “a single minute of silence throughout those two hours.”

The increasing number of Death Cafes is anecdotal evidence that people find talking about death worth their time. In a socially enjoyable setting where it’s safe to work through your thoughts and beliefs without judgment and dogmatism, Death Cafes help people face the subject.

“Remembering that I’ll be dead soon is the most important tool I’ve ever encountered to help me make the big choices in life.”— Steve Jobs, Stanford commencement speech in 2005

Finding or hosting a Death Cafe

Finding a Death Cafe is simple. Visit the online Death Cafe map to find one located near you.

If you can’t find a nearby gathering, consider hosting one. The Death Cafe franchise is clear about how to organize and lead a discussion. Visit their webpage for hosts and walk through the steps to gathering people together.

The human need to talk and connect is the thread binding generations, races, and cultures throughout history as it weaves through time. Death’s reality and mystery bind us in a common and intimate experience. Death Cafes offer people a friendly setting to explore and break death taboos without judgment.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!