— Could forests replace cemeteries?

From tree pods and mushroom suits to plain old dirt, death may have a greener future.

The way humans live impacts the world. So does the way they die.

It isn’t death itself that creates an ecological nightmare, but rather the resource-intensive processes we’ve devised for dealing with the dead. On top of all the land that’s set aside for graveyards, building caskets requires around 30 million board feet of wood and 90,000 tons of steel each year (that’s more steel than you’ll find in the Golden Gate Bridge). Grave vaults guzzle up 1.6 million tons of concrete annually. And 800,000 gallons of toxic chemicals like formaldehyde go into embalming — chemicals that often wind up seeping into the ground. (Oh, and all these stats are for the U.S. alone.)

Cremation, which has edged out burial as the most popular option in the U.S., requires vast amounts of energy to maintain the 1,800 degrees Fahrenheit needed to incinerate a corpse, which can take two hours or more. In the U.S., the process releases about 250,000 tons of CO₂ into the atmosphere annually — the equivalent of burning more than 30 million gallons of gasoline — and a significant amount of mercury from dental fillings.

By now you may be thinking, “There’s got to be a better way.” There is.

We already have several eco-friendlier ways of dealing with the dead, and more than 50 percent of Americans are considering them. These methods can be as simple as wrapping bodies in cloth and lowering them into the ground to decompose, or as cutting-edge as human composting and mushroom suits. There are also culture-specific traditions like the Tibetan sky burial, in which the dead are dismembered and left on mountaintops to be feasted upon by vultures.

In her short story The Tree in the Back Yard, a finalist in Fix’s Imagine 2200 climate-fiction contest, author Michelle Yoon envisions a future in which green burial practices have become commonplace. In the opening scene, the main character, Mariska, chooses a tree that her father’s remains will nourish via a receptacle called an Eternity Pod. Later, when she goes to visit his final resting place, Mariska sees “Trees of all types, all ages. Trees as far as her eyes could see,” each one marking a natural burial site.

How close are we to the future Yoon imagines?

The modern green burial movement

Generally speaking, a green burial is one that encourages the natural process of decomposition. That means no embalming, fancy caskets, or headstones. In the most straightforward application, remains are placed in a simple box or cloth, and interred at a depth of about 3½ feet — roughly half the proverbial 6 feet under — where there’s more microbial activity in the soil.

The modern movement emerged about 30 years ago as some sought to reclaim the intimacy and filial responsibility that is lost when a third party takes ownership of the dead, says Hannah Rumble, a social anthropologist at the University of Bath’s Centre for Death and Society in England. “It was almost kind of a re-enchantment — this idea that our dead were a fertile source for new life, if we put them in sensitive ways back in the environment,” she says. “Rather than seeing a corpse as yucky and icky and something that needs to be sanitized and hidden away, actually the corpse, in its very decomposition, could be quite useful.”

Much like other eco-conscious movements — local food, right-to-repair, and living off the grid, for example — green burial, at its heart, is about reclaiming and re-familiarizing ourselves with a process. In this case, death.

In some cultures, elements of these practices are the norm already. Traditional Jewish burial involves family members washing and preparing the body, dressing it in a shroud, and burying it in a simple pine coffin, or no coffin at all. Although this practice is based on ancient Jewish law, it aligns with much of the green burial ethos. “It emphasizes simplicity, equality in death, and return of the body to the earth,” says Rabbi Seth Goldstein.

Muslim tradition similarly involves ritual bathing of a corpse, wrapping it in a cloth, and burying it without a casket, facing Mecca. In both customs, the funeral happens as quickly as possible after the person has died — which respects religious teachings about honoring the dead but also makes sense biologically. Without embalming or other forms of preservation, bodies must be interred ASAP, for obvious reasons.

Much like other eco-conscious movements, green burial is about reclaiming and re-familiarizing ourselves with a process. In this case, death.

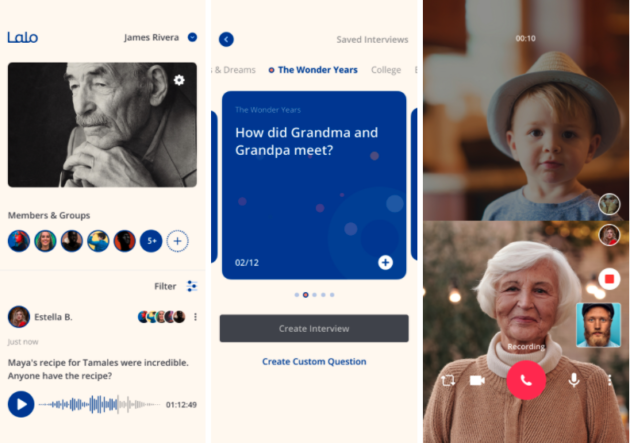

Although straightforward burial can be made more sustainable, an increasing number of alternative methods that promise to make death not only sustainable but beneficial to the earth have captured the imaginations of entrepreneurs and designers — and some have become legit options. Human composting (or, as proponents prefer, “natural organic reduction”) made headlines earlier this year when Recompose, the first fully operational human composting facility, opened its doors in Kent, Washington. Colorado legalized the process this year, and Delaware, Hawaii, Maine, New York, Oregon, and Vermont are considering it.

Then there’s the mushroom suit, which actor Luke Perry was famously buried in. The sleek, black “infinity burial suit” is made of organic cotton and specially cultivated fungi, which the company claims help detoxify the corpse and deliver its nutrients to the soil.

What’s shown in The Tree in the Back Yard is a form of tree burial — the burial of human remains (cremated or otherwise) in a biodegradable “pod,” from which a tree will grow, letting the remains nourish its roots. Italian company Capsula Mundi (or “the world’s capsule”) has designed egg-shaped urns intended to feed saplings planted above them. So far, the only product it has on the market is an urn for ashes, but the company intends to pilot a larger pod that could hold a human body.

Legal and cultural barriers, and the future

The largest obstacle to something like Yoon’s vision of a full graveyard of trees growing from burial pods is not the technology, but the stigmas and laws it needs to overcome.

Death is a deeply emotional, ritualistic affair in most parts of the world, and customs (or outright rules) around dealing with the dead can be stringent. “Unless you’ve got a country whose population follows one particular cultural or religious tradition, I think it’s kind of impossible to say that you’ll have a wholly burial culture or a wholly cremation culture in a country,” says Rumble. Some religions necessitate cremation, like Hinduism, while other teachings support burial in specific ways. According to Rumble, that means there will always be a need for multiple options.

But that doesn’t mean newfangled approaches like tree burial and human composting can’t be compatible with religious teaching and rituals. For Goldstein, who lives and practices in Washington, human composting has become a real option for members of his community. And although it isn’t traditional, Goldstein finds that the practice can uphold Jewish teachings and values and shouldn’t necessarily be dismissed as non-Jewish.

“I can’t declare pork to be kosher all of a sudden,” he says. “But other things have more fluidity, in terms of the intersection between spiritual values and tradition and new technologies.” Goldstein puts the onus on himself and other religious leaders to find opportunities to make meaning out of these new approaches, rather than saying no to what people of faith want for themselves or their loved ones. “Sometimes people ask me, ‘Is this OK?’ And I think that really what they’re asking is, ‘How do we make this Jewish?’”

As for simpler green burials replacing the chemical- and resource-intensive methods, other barriers must be overcome. In the Western world, the sanitized approach to handling dead bodies doesn’t just reflect our culture — it has also made its way into our laws. Some states require embalming or refrigeration of bodies that have been dead for more than 24 hours. If families haven’t planned ahead, that doesn’t leave much time to make arrangements at a natural burial ground.

“Some jurisdictions [also] mandate the use of concrete liners,” Goldstein says, which wouldn’t traditionally be used in Jewish burial and aren’t compatible with the green approach, either. In 2008, a county in Georgia passed an ordinance requiring leak-proof containers for corpses, due to a complaint about a proposed green burial site. Most states allow home burial on private property, but some also require special permits to do so and a handful of states mandate that a funeral director be on hand.

Even if it’s not law, each cemetery sets its own policies and requirements. According to the Green Burial Council, only 335 cemeteries across the U.S. and Canada offer green or conservation burial options (there are more than 144,000 total cemeteries in the U.S.). A majority of those are hybrid cemeteries, and some are also Jewish or otherwise affiliated.

But the list has been steadily growing. In 2018, 54 percent of Americans said they were considering a green burial, and 72 percent of cemeteries reported increased demand for eco-friendly options. There are all kinds of reasons for the shift, beyond the desire to live (er, die) more lightly on the planet. Natural burial options may be cheaper than ones involving ornate caskets, concrete vaults, and granite headstones. When a grave site is incorporated into the landscape, there’s no need to maintain or decorate it, which removes the fear of placing a burden on family members — or becoming the sad spectacle of an unloved grave.

And the desire to return to the earth, which has echoes in many religious teachings, appeals to many on a spiritual level. “Whether through the lenses of personal faith or secular society or science, we all recognize that circular notion of life and death,” Rumble says. Natural burial speaks directly to that, whether it’s in a simple cotton shroud or a mushroom suit. “The fact that, perhaps, you exist in some other form because your body’s gone back to the soil, that offers great solace to people,” she says.

And in fact, that very mindset shift may turn out to be more important than the emissions saved or the trees planted. As various forms of green burial begin to take root, they reinforce the idea that we humans are part of the natural world, and we have a responsibility to nurture it — in life as well as in death.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!