AS MEDICAL AND technological advances have made our world safer, it’s become much harder to kill oneself painlessly, even if one intends to. Asphyxiation by carbon monoxide, usually done by inhaling car exhaust in an enclosed garage, has gotten harder as the automobile industry’s emissions levels lower over time. Ovens have followed a similar trend, with natural gas models outplacing those that run on coal. The shift is especially true when it comes to medications. Use of Nembutal, the barbiturate that killed Marilyn Monroe, declined in the second half of the 20th century and was eventually discontinued in the United States, leaving available fewer substances that can cause a nonviolent overdose. (Other lethal medications have multiplied in price, sometimes threefold or more.) For those who desire “rational” suicide — done after consideration rather than, as is more typical, spontaneous despair — options are limited outside uncertain and gory methods. We live more protected lives than we once did, but, in exchange, the ability to end our lives peacefully is kept out of reach, like a bottle of recalled pills.

The subjects in Katie Engelhart’s essential, vulnerable book, The Inevitable: Dispatches on the Right to Die, question these barriers. Since the mid-20th century, conversations on assisted suicide have grown, as laws allowing it have passed around the world. In popular conversation, Engelhart writes, people who use assisted death usually fit an archetype: elderly, secular, white people, with terminal diseases and supportive families, take advantage of rare right-to-die laws soon before their likely natural death. They throw back a lethal cocktail of liquid drugs under the watch of a doctor and their loved ones. They fall asleep, and, within a few hours, their heart stops. “While most reporting about the so-called right to die ends at the margins of the law, there are other stories playing out beyond them,” Engelhart writes. “Didn’t I know that whenever the law falls short, people find a way?”

Engelhart, a former reporter for VICE and NBC News, profiles two rogue doctors and four subjects who seek assisted death in a variety of illicit shades: an elderly British woman who feels she has lived the life she wants; an American woman in her 30s with worsening multiple sclerosis; an American woman sinking into dementia’s abyss; and a 25-year-old Canadian man with complicated, severe depression. Engelhart profiles them as they either seek help with suicide, through mail-order chemicals or services overseas, or challenge the limits of their country’s laws. Engelhart is ever thoughtful; the approach can fall flat during meetings with secondary doctors or interviews with philosophers (summoning more than one description of office shelving), but Engelhart’s main portraits, and her careful relationships with her subjects, powerfully animate her central questions: what is dignity, and what does it mean to die with it?

As she chases dignity’s meaning, Engelhart meets early dead ends. Some of her interviewees brush off the question, saying that dignity amounts to feeling respected, making their own choices, and, mostly, being able to wipe their own asses. (“When someone has to change my diaper, I don’t want to live.”) But if dignity can be understood at an individual level, it is twisted by the systemic factors Engelhart describes that lead to death wishes: the specter of melancholic senior living facilities, unsuccessful mental health treatments, and impossibly expensive health care. The Inevitable is international in scope, but these pressures loom largest in the American medical system. When visiting Brussels, Belgium, Engelhart speaks to Wim Distelmans, an oncologist and euthanasia proponent, about whether assisted death should be offered to more people in the United States. “It’s a developing country,” he tells her. “You shouldn’t try to implement a law of euthanasia in countries where there is no basic healthcare.” A reader wonders, then, what it means to assert dignity within circumstances that do not do the same.

¤

Voluntary euthanasia may appear in Thomas More’s vision of Utopia, but doctors have long struggled to write it into their job descriptions. In 1995, the American Medical Association stated that “[p]hysician-assisted suicide is fundamentally incompatible with the physician’s role as healer,” and the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization opposes the practice. The membrane between palliative care and assisted suicide is thin, though — in some cases, tending to fading life with pain-relieving drugs functions as a kind of assisted death, albeit a slow one. Engelhart roots this dissonance in the 20th century’s effort “to conceptually transform old age from a natural phase of life into a stage of disease,” she writes, “and, by extension, something to be defeated, rather than embodied or endured.”

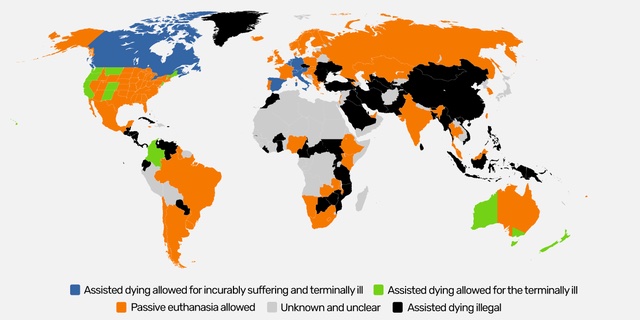

Assisted suicide has been legal in Switzerland since 1940, and some other European countries, like Belgium, have allowed it since the 1990s. (Parts of Australia and Canada allow it, too.) Its American history is piecemeal. As health-care prices climbed sharply in the 1970s and ’80s, a string of high-profile cases of young white women on life support drummed up public conversation. Then, in 1994, Oregon became the first state to legalize assisted death. Other states followed Oregon’s strict parameters: a patient must be terminally ill and have six months or less to live, and they must have the mental capacity to make the decision, as determined by a doctor. On their chosen deathbed, a doctor will give them the lethal barbiturate, but they must lift it to their own mouth in a final, performative gesture of agency.

Opponents of assisted death have long argued that the practice will fall down a slippery slope of exploitation. Poor patients and the elderly, critics say, will feel pressured to die rather than rack up medical costs for their families. People with depression will choose it over trying more treatments. Historically, voluntary euthanasia and eugenics attract similar supporters, and today, some disability rights groups warn that the practices are “fatally tangled.” (One doctor Engelhart speaks with wants to create machines that can provide assisted death more easily than drugs; he sheepishly describes one of his coffin-like prototypes as “a little Auschwitzy.”) So far, though, there is no evidence from Oregon or other states that the laws have caused disproportionate deaths in any demographics. In fact, the opposite might be true. Engelhart spoke to doctors who knew of patients who qualified under the laws, and who wanted to die, but who could not afford the drugs. “Poor patients sometimes had to live,” she writes, “while richer patients got to die.”

¤

Like much great narrative journalism, The Inevitable powerfully justifies its form when mapping how people relate to each other outside dominant systems — in this case, how end-of-life care can exist away from, or in opposition to, big medicine. Beyond trickster doctors like Jack Kevorkian — the American pathologist, dubbed “Doctor Death,” who in the 1990s turned assisting suicides into a kind of civil disobedience — barely underground networks have offered assisted death to people who don’t meet the law’s eligibility. One of Engelhart’s subjects, Debra, is a widow in Oregon who does not want to fully succumb to her dementia. She ends her life before that happens with the help of the Final Exit Network, a group of volunteers who instruct the elderly on how to commit suicide and accompany them through it. When she is ready, two volunteers arrive at her house, hug her, and kneel next to her wheelchair while she uses a plastic bag and gas canister to stop her own breathing. Even with its analog methods, this moment feels dignified, closer to what care should look like — especially when put into relief by the police who show up to her door some hours later.

Other narratives are murkier. A woman named Maia, the only main subject from the book who is still alive, speaks with Engelhart while working through the decision to schedule her death at a clinic in Basel, Switzerland, seeking relief from multiple sclerosis. Maia is slowly and painfully approaching paralysis. “I believe the soul travels on and wants to be free from this prison that has become my body,” she wrote in her application to the clinic. Maia felt early, undiagnosed symptoms of her MS in her 20s, but, following the advice of her father, she hoped for the best and declined treatment. Once the debilitation became obvious, she wondered whether those early treatments would have prevented the disease’s severe progression. The future she is left with will require constant assistance and treatments. In the United States, it will send her into poverty. (She unsuccessfully attempts the most American of options: a GoFundMe for medical expenses.) Maia is sure of her plan, but she seems consumed by wondering whether she could have lived a different life or whether she has suffered enough to end the one she has. Even with her Swiss appointment, she closely follows right-to-die bills in the United States. “On an idealistic level,” she tells Engelhart, “I’m obsessed with dying in my own country.”

For Maia, it seems, dying in the United States would be a kind of acknowledgment, an agreement that her country shares responsibility for her distress. The Inevitable is interested in dignity and how people define it, but it does not ask so explicitly whether the state, and the laws it creates, can recognize people’s dignity in the first place. If our systems of governance fail to care for so many — and kill others on death row and in the streets — can they be trusted to control the choice to die? If a “developing country” without universal health care did offer wide access to assisted death, one wonders whether its use could make that country’s ills more obvious, more urgent, less ignorable. When The Inevitable snaps back to the perspectives of its individual subjects, the implications of these political threads can get lost; the perspectives of nonwhite patients, or people who harbor more doubt in the medical system from the get-go, are also mostly absent from the narrative. Still, the book’s brilliance is in how much fertile ground it lays for these questions.

Near the end of The Inevitable, Engelhart profiles Philip Nitschke, an Australian doctor who has become one of the most vocal supporters of the unrestricted right to die. Nitschke founded Exit International, another organization like Final Exit Network. His is far more boundless than others; they sell The Peaceful Pill Handbook (2006) to almost anyone with instructions for safe suicide methods, and Nitschke gives public “DIY death seminars” with his wife’s help. He is at the radical end of the book’s spectrum, yet after the rigid patterns of death barely evaded by Engelhart’s subjects, his beliefs appear risky but benevolently imaginative.

When Nitschke started his career, he only accepted assisted death on a limited scale. But as he met the kind of people who could be in The Inevitable: Dispatches on the Right to Die — a taxi driver with stomach cancer, for one, who died painfully without the legal right to die — these limits dissolved rapidly. What did age have to do with it, really? And, more than that, if physical pain was an acceptable reason to end one’s life, shouldn’t mental pain be, too? Doctors and lawmakers, he came to believe, couldn’t pick and choose. There was simply too much gray area. “Philip came to think that efforts to suppress rational suicide were ‘a sign of an increasingly sick society,’” Katie Engelhart writes. “They were a sign that, maybe, society wasn’t so confident in its reasons for insisting on life.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!