The process of acceptance and letting go builds the resilience necessary to navigate an array of life’s obstacles.

By Kerry Hannon

It’s been three months, and I still fight back tears when I’m reminded of the death of my Labrador retriever, Zena. The haunting image of finding her lying on the kitchen floor flashes back: her jaw clenched, eyes open and body lifeless but warm.

She was nearly 13, but there were no signs she was in distress when I left her 20 minutes earlier. Yet she was gone. I felt as if I let her down in some way. I wasn’t there for her.

When Zena was just a few months old, she curled up on the bed with my 88-year-old father, as I held his hand, and he softly exhaled his last breath. My younger brother, Jack, died unexpectedly three years ago. I clung to Zena for comfort.

My first experience with death was losing my turtles, Charlie and Tina, at 6. I’ve since lost friends, relatives, other dogs, cats, horses. Decades later, Zena’s death has sharply reminded me how aching grief is.

Our pets are a part of the everyday fabric of our lives in a way that few human relationships are. When you lose one that is close to you, something inside shifts.

Smarter Living: A weekly roundup of the best advice from The Times on living a better, smarter, more fulfilling life.

And yet the death of a family pet can remind us of how vulnerable, precarious and precious life is. It’s that process of acceptance and letting go that builds the resilience necessary to navigate an array of life’s obstacles. We hone an ability to adapt to the evanescence of our lives with grace and hope.

“We’re changed and transformed by the loss,” said Leigh Chethik, a clinical psychologist in Chicago. “It brings impermanence and death into an updated internal, emotional map. This loss can help us with whatever comes next, whatever future losses may be in store. We come to see that we can create a new understanding and attach to new dreams.” Below are some ways in which the loss of a beloved pet can be a catalyst for personal growth.

Embracing Your Loss

“The idea that grief can often be the price of love is helpful in developing resilience,” according to Jessica Harvey, a psychotherapist in Portland, Ore., who specializes in pet grief. “By focusing on the positive elements of having a pet as the cause of why the hurt is so powerful when they are gone, we can begin to heal.”

Pets occupy a unique role in our lives. “They are usually our ‘roommates,’ part of the household, and they are typically a source of pure warmth and positive experience,” Ms. Harvey said. “How we are able to manage the temporary reduction of joy and warmth from the missing roommate can be a significant practice in resilience.”

That loss, of course, can have a startling depth. “For adults in their upper-20s to mid-30s it’s like losing their innocence as a new adult and being catapulted into reality,” said Dani McVety, a veterinarian and a founder of Lap of Love Veterinary Hospice, a national network of veterinarians dedicated solely to end of life care. “Many times, people in this age range got their dog or cat at the very beginning of their adulthood. This pet has witnessed them go through college, boyfriends or girlfriends, marriage, children, career developments, and so on. This pet has been the one constant in their life through their biggest growth years.”

How we handle the death of a pet “shapes how we deal with love and loss, conjoined emotions,” said Kaleel Sakakeeny, a pet loss and bereavement counselor who is based in Boston.

From Grief, Building Confidence

But how does that growth happen? One study, “Post-Traumatic Growth Following the Loss of a Pet,” conducted by Wendy Packman and others, of the Pacific Graduate School of Psychology at Palo Alto University, found that after losing a beloved pet, many of the participants reported an improved ability to relate to others and feel empathy for their problems, an enhanced sense of personal strength, and a greater appreciation of life.

Lynn Harrington, who lives in The Plains, Va., lost her 15-year-old Norwich terrier, Hap, about a year ago. “For many months, I couldn’t shake the sadness,” Ms. Harrington said. “And during these sad times, I finally remembered a lesson I learned many years ago with the loss of my first dog: Animals that come into our lives are gifts to us and can never be replaced. However, another animal can come to us and help us heal our hearts.”

Shortly after that epiphany, a friend told her about a senior dog that needed a home, and a match was made. “There isn’t a day that I don’t think of Hap through a photo, a memory shared, or even some funny mannerism I see of him in my rescue dog,” Ms. Harrington said. “These moments remind me that I’m grateful for the animals in my life — they teach me about love and that I’m resilient even in times of great challenge or sadness.”

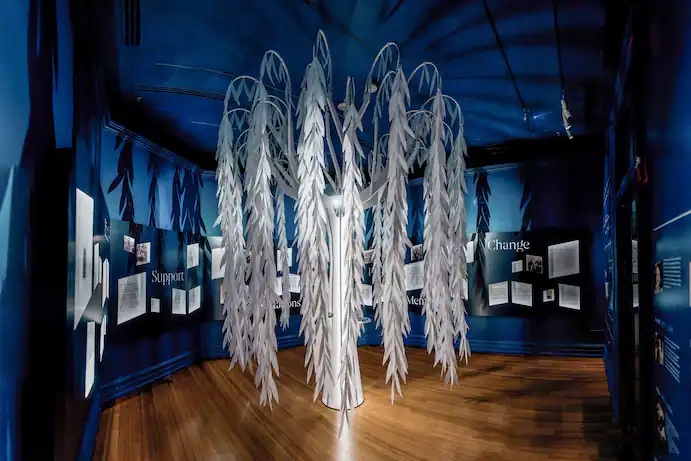

Remembrance itself — though photos and memorials — can be healing. “Grief is ongoing,” Ms. Packman said. “Remaining connected to your beloved pet after death can facilitate the bereaved’s ability to cope with loss and the accompanying changes in their lives. Our findings suggest that those who derive comfort from continuing bonds — holding onto possessions and creating memorials for their pet — may be more likely to experience post-traumatic growth.”

Life Lessons for Children …

For children, the loss of a pet can be “a dress rehearsal for losing a human family member,” Dr. Chethik said. “With the death of a pet, kids are often exposed to a new existential crisis or struggle: the idea of impermanence and mortality. Things we love and care for are not around forever. We can and will lose what and who we love. And we can’t go where we may typically go for comfort — to our pet.”

For children, this process can be hard to grasp. The death of a family pet can trigger a sense of grief in children that is deep and lingering and that can possibly lead to subsequent mental health issues, according to a new study by researchers at Massachusetts General Hospital.

“The impact can be traumatic,” wrote Katherine Crawford, the lead author of the paper. “We found this experience of pet death is often associated with elevated mental health symptoms in children, and that parents and physicians need to recognize and take those symptoms seriously, not simply brush them off.”

Dr. Chethik added: “A child needs to actively grieve and process the loss,” he said. “The attention, support, honesty, sharing and understanding the child receives during this time of grief will them create an emotional template for the human losses that will inevitably come their way.”

With support from parents and others, the loss of a pet can be a way for children to move forward. “Teaching children how to say goodbye and that the difficult emotions that accompany grief are OK to feel is a powerful lesson,” Ms. Harvey said. “Children learn that this painful experience does start to feel better eventually, and that other difficult situations in the future can as well.”

… And for Adults

I’ve reminded myself these past months not to rush the process. Grief slides from the heart in its own time. I’m still talking to Zena and reflexively looking for her when I wake up in the morning. Yet, I know that soon my husband and I will be ready for a next chapter with a new companion.

This is the second dog we’ve lost during our marriage. We’ve grappled with the sadness each time, but we both know from experience that the love and laughter a pet brings into our lives are worth it.

As Ms. Harrington said, “Just knowing I can move through that kind of pain and get to the other side really does translate into that lesson that even when things in other parts of my life seem dark, I just need to keep moving through it and the unexpected can happen, bringing joy or opportunity.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!