By Judith Graham

Nothing so alters a person as learning you have a terminal illness.

Ronni Bennett, who writes a popular blog about aging, discovered that recently when she heard that cancer had metastasized to her lungs and her peritoneum (a membrane that lines the cavity of the abdomen).

There is no cure for your condition, Bennett was told by doctors, who estimated she might have six to eight months of good health before symptoms began to appear.

Right then and there, this 77-year-old resolved to start doing things differently — something many people might be inclined to do in a similar situation.

No more extended exercise routines every morning, a try-to-stay-healthy activity that Bennett had forced herself to adopt but disliked intensely.

No more watching her diet, which had allowed her to shed 40 pounds several years ago and keep the weight off, with considerable effort.

No more worrying about whether memory lapses were normal or an early sign of dementia — an irrelevant issue now.

No more pretending that the cliche “we’re all terminal” (since death awaits all of us) is especially insightful. This abstraction has nothing to do with the reality of knowing, in your gut, that your own death is imminent, Bennett realized.

“It colors everything,” she told me in a long and wide-ranging conversation recently. “I’ve always lived tentatively, but I’m not anymore because the worst has happened — I’ve been told I’m going to die.”

No more listening to medical advice from friends and acquaintances, however well-intentioned. Bennett has complete trust in her medical team at Oregon Health & Science University, which has treated her since diagnosing pancreatic cancer last year. She’s done with responding politely to people who think they know better, she said.

And no more worrying, even for a minute, what anyone thinks of her. As Bennett wrote in a recent blog post, “All kinds of things . . . fall away at just about the exact moment the doctor says, ‘There is no treatment.’ ”

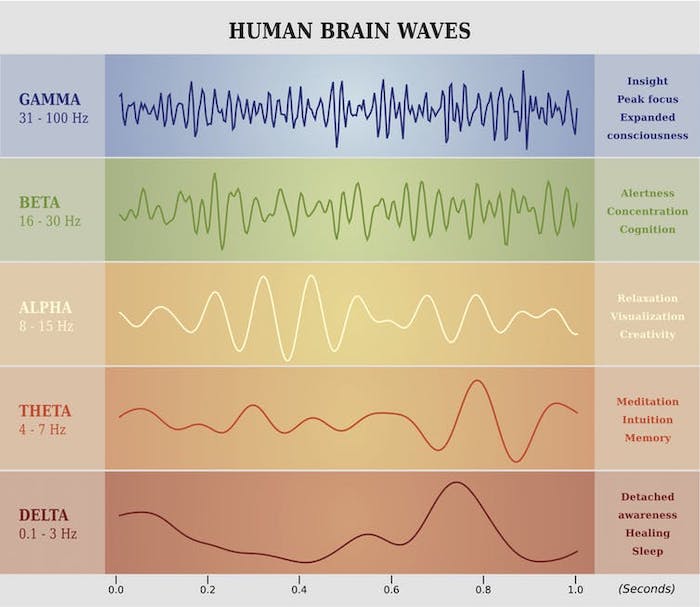

Four or five times a day, a wave of crushing fear washes through her, Bennett told me. She breathes deeply and lets it pass. And no, psychotherapy isn’t something she wants to consider.

Instead, she’ll feel whatever it is she needs to feel — and learn from it. This is how she wants to approach death, Bennett said: alert, aware, lucid. “Dying is the last great adventure we have — the last bit of life — and I want to experience it as it happens,” she said.

Writing is, for Bennett, a necessity, the thing she wants to do more than anything during this last stage of her life. For decades, it’s been her way of understanding the world — and herself.

In a notebook, Bennett has been jotting down thoughts and feelings as they come to her. Some she already has shared in a series of blog posts about her illness. Some she’s saving for the future.

There are questions she hasn’t figured out how to answer yet.

“Can I still watch trashy TV shows?”

“How do I choose what books to read, given that my time is finite?

“What do I think about rationale suicide?” (Physician-assisted death is an option in Oregon, where Bennett lives.)

Along with her “I’m done with that” list, Bennett has a list of what she wants to embrace:

Ice cream and cheese, her favorite foods. Walks in the park near her home. Get-togethers with her public affairs discussion group. A romp with kittens or puppies licking her and making her laugh. A sense of normalcy, for as long as possible. “What I want is my life, very close to what it is,” she explained. And deep conversations with friends. “What has been most helpful and touched me most are the friends who are willing to let me talk about this,” she said.

On her blog, she has invited readers to “ask any questions at all” and made it clear she welcomes frank communication.

“I’m new to this — this dying thing — and there’s no instruction book. I’m kind of fascinated by what you do with yourself during this period, and questions help me figure out what I think,” she told me.

Recently, a reader asked Bennett if she was angry about her cancer. No, Bennett answered. “Early on, I read about some cancer patients who get hung up on ‘why me?’ My response was ‘why not me?’ Most of my family died of cancer and, 40 percent of all Americans will have some form of cancer during their lives.”

Dozens of readers have responded with shock, sadness and gratitude for Bennett’s honesty about subjects that usually aren’t discussed in public.

“Because she’s writing about her own experiences in detail and telling people how she feels, people are opening up and relaying their experiences — things that maybe they’ve never said to anyone before,” Millie Garfield, 93, a devoted reader and friend of Bennett’s, told me in a phone conversation.

Garfield’s parents never talked about illness and death the way Bennett is doing. “I didn’t have this close communication with them, and they never opened up to me about all the things Ronni is talking about,” she said.

For the last year, Bennett and her former husband, Alex Bennett, have broadcast video conversations every few weeks over YouTube. (He lives across the country in New York City.) “What you’ve written will be valuable as a document of somebody’s life and how to leave it,” he told her recently as they talked about her condition with poignancy and laughter.

Other people may have very different perspectives as they take stock of their lives upon learning they have a terminal illness. Some may not want to share their innermost thoughts and feelings; others may do so willingly or if they feel other people really want to listen.

During the past 15 years, Bennett chose to live her life out loud through her blog. For the moment, she’s as committed as ever to doing that.

“There’s very little about dying from the point of view of someone who’s living that experience,” she said. “This is one of the very big deals of aging and, absolutely, I’ll keep writing about this as long as I want to or can.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!