— Can our presence at the last breaths of a loved one help us heal?

By Elaine Soloway

My mother’s last words to us were, “Drive carefully.” She had been admitted to a Chicago hospital a few days earlier after signs of a heart attack. It was Dec. 19, 1981, just shy of her 69th birthday on January 30.

As directed by Mom, with my spouse at the wheel, we drove silently home, grateful she was in the good hands of her internist and in one of Chicago’s most prestigious medical centers. But in the middle of that same night, we were awakened by a phone call. I lay silent as my spouse picked up the receiver. I listened, then watched as he pulled a tissue out of the nearby box and handed it to me. “Your Mom died,” he said.

I had no idea her condition was that grave. I pummeled my pillow, soon damp with my tears, shattered I had not been there for her final breaths.

They are likely thinking of my eventual last breaths and are hoping to avoid the trauma and frantic flights that would get them to me in time.

That long ago scenario has resurfaced because my adult children, who live on the East Coast, are asking me to move from Chicago to Boston where I’d be closer to them and my grandchildren. I am 85 and gratefully in good health. But they are likely thinking of my eventual last breaths and are hoping to avoid the trauma and frantic flights that would get them to me in time.

I understand my children’s worries. When my mom died, I dreaded my call to my brother, who lived in Kansas City, Missouri. “Why didn’t you let me know it was so serious?” he charged. “I could’ve flown there and seen her before she died.”

My apologies tumbled with my tears. “I didn’t know it was so serious,” I said. His grief, and my guilt, affected our close relationship. It was as if I had deliberately kept silent because he was her favorite.

Gratefully, we moved on to have a loving relationship. Frequent phone calls and occasional visits to each other’s town were salve. When he became seriously ill at 83, I traveled to see him. But when he died a few days later, I was not there for his final breaths.

‘Please Don’t Let Daddy Die’

Long before my mother’s death, I missed the last breaths of my father. He was 47, a heart attack fueled by diabetes, smoking three packs of Camels a day, and obesity. It was 1958 and I was a 20-year-old student at Roosevelt University when I was called to the school’s office to take a phone call from my uncle. “Get to the hospital right away,” he said.

Hospice workers report that some people who are dying wait to be alone for their final breaths.

I remember racing down several flights of marble stairs. “Please don’t let Daddy die,” I repeated as I sought a cab. But Dad was already gone when my uncle had called. My uncle met me outside of Dad’s room. And with his arm around my shaking body, said, “I’m so sorry; he’s gone.” I missed his final breaths, but I’m certain his labored words would have included, “I love you, Princess.”

My second husband, Tommy, was in hospice at our home after suffering several years of frontal temporal degeneration (FTD) and lung cancer. Neighbors helped me move our queen-sized bed to a different corner of our bedroom and assemble a hospital bed with guardrails. Although some had urged me to move Tommy from the hospital directly to a hospice center, I refused. I wanted him to know I was with him ’round the clock, not miles away where he might feel abandoned, and I bereft.

“I’ll be downstairs,” I told him one night. “And I’ll be up to kiss you goodnight before I go to sleep.” He smiled and squeezed my hand. I had barely settled on the couch when the hospice worker appeared at the top of the stairs. “He’s gone,” she said.

I learned this pause is not unusual. Hospice workers report that some people who are dying wait to be alone for their final breaths.

Now I have far outlived both parents and a husband. I doubt that fact has mollified my children’s concern about the 984 miles that stretch long and unknown between us. I am grateful for our strong relationship. I understand that their careers and own family obligations have skimmed our in-person meetings in Chicago to just a few times a year.

Looking for Peace

But what if I did heed their request and slice those miles to a more manageable five-minute car ride away? Then, if my fatal day arrived in their own backyard, they might be able to be part of a Jewish ritual that could bring all of us peace.

“So often, the experience of a loved one dying gets crowded out by the emotional needs and agendas of family members.”

In my search for end-of-life healing, I found “The Last Breath — Enriching End of-Life Moments” published in the medical journal JAMA by Dr. Martin F. Shapiro, who is a member of the Department of Medicine at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York.

He writes, “In Jewish tradition, the soul leaves the body with the dying breath, and it aids the soul on its journey if those present say a prayer, ‘The Shema” (“Hear O Israel, the Lord is our God, the Lord is One”) as the individual breathes their last breath.”

In his remembrance of his own mother’s death, Shapiro explains, “I certainly did not believe that our words had provided Mom with a ticket to heaven … what we did discuss, and all agreed on that it was a wonderful experience … So often, the experience of a loved one dying gets crowded out by the emotional needs and agendas of family members. Saying this prayer structured our experience in a positive way.”

I realize that even if I did move to Boston, we could emulate the scene in Chicago when despite living in the same city as my parents, or just downstairs from my husband, I missed their last breaths. But at least they would not have to endure an airplane ride with their hearts mimicking a flight’s turbulence.

Should last breaths be enough of a reason for me to move 984 miles away from my current home?

I’ll leave that to my children.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

I Was Looking The Other Way When Death Surprised Me

— I didn’t see him coming.

I’d heard about Pattie before I’d ever met hershe was a psychic.

My friend Lissa had done a one-woman show and had talked about her psychic. Since Lissa was the owner of a theater, soon, everyone was going to see Pattie, who wasn’t only a psychic but an empath.

I had to check out Pattie’s skills for myself and made an appointment. Pattie lived in the same town as me but on a cul de sac further up in the hills. It was remote enough that deer came into her garden and ate her flowers, but not so far that she didn’t get trick-or-treaters.

Walking into Pattie’s house as she requested, I felt strange, and I always knocked and called out when I entered. She usually had four or five cats sleeping in boxes scattered throughout her living room.

Pattie was seated at a table in a little room with a cat in her lap and a tumbler full of iced tea at her side. She was a large woman with vivid blue eyes and a warm smile.

She enjoyed her work and loved people, and she didn’t fear the spirit world as she often communicated with them.

My mother has been dying for months; I have a cat with a brain tumor and another cat who is getting up there in years. When any of them die, it won’t be a surprise. I’ll be as ready as one can be.

What I wasn’t ready for was the death of someone outside of those three.

But Death is a trickster and hates to be predictable. He refuses to operate on anyone else’s timetable and does what he pleases.

I found out as I was waiting for my mother to die that Death came along and took my friend, Pattie, to the hereafter.

When I heard from a mutual friend that Pattie was in the hospital — it didn’t sound especially serious.

She was in her seventies, had Multiple Sclerosis (MS), and had some health issues this past year, but Pattie was also the most positive person I know, and she was resilient. She’d gone into the hospital on a Thursday, and I fully expected her to be out by Monday, laughing about the experience.

After my initial consultation, I saw Pattie regularly for a few years.

I’d crack the both of us up with my opening questions, “What do you hear?”

What were the spirits telling her that I needed to know?

Besides her psychic abilities, Pattie could read people, and much of the time, it felt like she was reading me more than she was getting info from the great beyond.

I also encouraged her to use the tarot cards with me as I felt the cards gave structure to our sessions and gave the proceedings a gravitas. The tarot cards made me feel she was being guided, not making things up on the spot.

Eventually, I couldn’t rationalize paying a bunch of money to an unlicensed therapist, but we stayed friends.

We went to a couple of dinner theater productions, and out to eat (which was challenging after she had weight-loss surgery,) talked on the phone, and sent texts and cards.

She was immensely proud and supportive of my writing, and I shared my favorite stories with her. She was one of my supplemental mothers who loved me unconditionally and always remembered my birthday.

I said before that she was an upbeat person — someone who made the best out of a tough situation.

One time, Pattie fell down the escalator at Target. Rather than being embarrassed, she befriended the paramedics, asking their names, finding out their stories, and making them laugh as they loaded her onto a stretcher and into the ambulance.

I thought this time in the hospital would be another event, but it turned into a funny anecdote about how Pattie had charmed even the snottiest surgeon or caused all the nurses to fall in love with her.

“I don’t know if this is the right thing to do or say,” my friend Poppy said, “but Pattie is dead. She died in her sleep.”

Yes, Pattie died how I wanted my mother to go — peacefully and in her sleep.

Death had gotten his wires crossed, or maybe it was deliberate on his part.

Why now?

Pattie loved Christmas and would often decorate her house to maximum Christmasness. I sent her a Christmas card last week and wished her a happy and healthy New Year.

I’m not ready to mourn her — my grief has already been parceled out. I’m at full capacity, and yet, I do grieve because not grieving is the same as not being grateful for knowing her and having someone as kind and good as she was in my life.

How often have Lissa, Poppy, and I discussed arranging a group lunch date with Pattie? We always put it off for when we weren’t so busy or for other silly reasons.

We thought there’d be plenty of time to get together — we didn’t know Death was lurking nearby.

Pattie may be gone, but I’m not ready to say goodbye.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

How To Die Well

– Meet The Death Positive (Or Accepting) Practitioners

Have we lost the ability to die ‘well’?

By Tessa Dunthorne

Dead Uncertain: Why We’re Disconnected From Death

‘I was lucky, in a way,’ considers Dr Emma Clare. ‘I was brought up by my grandparents, so I always had that awareness that they were closer to the end of life than most people’s parental figures. We were also very immersed in nature, my grandad always outdoors in the Peak District, and bringing home dead wildlife to look at and appreciate. We especially liked birdwatching, and sometimes he’d find [dead] birds, like hawks, that you don’t often get to see up close – he’d call me outside, we’d have a look, and we’d be like, “wow, isn’t life amazing”.’

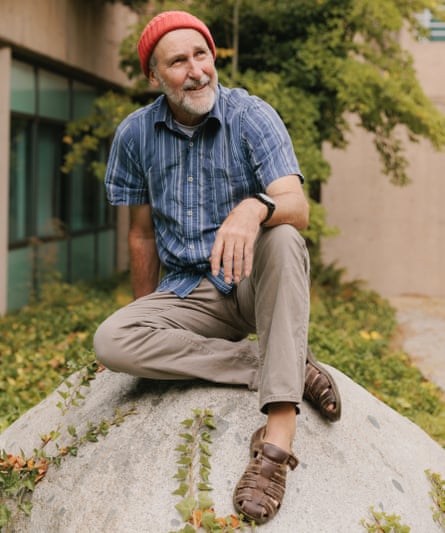

Emma is an end of life doula and has a PhD in death competency from the University of Derby. Not dissimilar to the doulas who stand alongside midwives for new mothers, she is one of the palliative and post-life care workers who step up in difficult times to hear the wishes of the dying, facilitate conversations for newly bereaved families, and provide a strand of support that the medical system cannot give. In short, she – and her peers – are the people who make death a bit more human – because, essentially, we’ve lost the ability to die well. And it’s come in no small part from our increasing disconnection from nature.

In a recent episode of environmental journalist Rachel Donald’s podcast Planet: Critical, agroecologist Nikki Yoxall bemoans how we’ve begun to think of death in nature as a waste – as something we should try to fix. She argues that we’re increasingly ‘cleansed from decay’, a cycle within which all living things exist; that the invention of plastic itself can be credited with this alienation, as a material that defies that natural cycle with its foreverness.

We’re also experiencing a wholesale nature deficit. Rewilding Britain suggests that 90 percent of our time is now spent indoors; we’re less food and nature literate, too The biggest indicator of this is how we’re living beyond the limits of nature, having transgressed six of the nine planetary boundaries set out by climate scientists. But it’s also cropped up in an unexpected way: how we interact with and experience the inevitability of death.

Like plastic, we’re now approaching a technological crux in history where we can (to an extent) deny the natural cycle of life and death (just look at the tech bros in Silicon Valley dropping millions in the search for everlasting life). Human beings have also, of course, made strides in medicine that have almost doubled our lifespans. But by doing so, argues Emma, we have also medicalised our experience of death.

‘Medical advancement is obviously a good thing,’ says Emma, ‘but it makes us feel like we’re aside from nature – that we can conquer death. And we think we know how to avoid it, when actually we don’t – we only know how to prolong the dying process.’

Dr Kathryn Mannix, the palliative care doctor behind With The End In Mind (William Collins, £9.99), argues that medicalisation has radically altered our experience of death. Or, rather, ended our experience of death. ‘Instead of dying in a dear and familiar room with people we love around us,’ she states, ‘we now die in ambulances and emergency rooms and intensive care units, our loved ones separated from us by the machinery of life preservation.’

Emma agrees. ‘One of the reasons that this discomfort starts in society is that a lot of our deaths are now behind closed doors, whereas even a hundred years ago, most people died at home with kids around.’

University of Exeter’s Dr Laura Sangha, a specialist in early modern death cultures, points out that frequent observance of dying in the past didn’t affect the gravitas of loss. ‘Seeing death more, particularly among young children, didn’t mean you grieved less,’ she says, ‘evidence points to parents and children having strong bonds, and parents experiencing heartbreaking suffering when they lost their offspring. But the fact that it was more likely to happen would have meant that you developed strategies to emotionally prepare.’

Other cultures still retain this emotional preparedness, suggests mortician-cum-YouTuber Caitlin Doughty in her book From Here To Eternity (Orion, £8.99). It sees her go around the world following different practises of mourning and burial. She found that Westernised society has shed holding space for the bereaved to grieve openly and without judgement.

In contrast, she found that the Toraja people, from South Sulawesi, Indonesia, embalm the bodies of loved ones and maintain them for years after a person dies, until their burial (after which they are often exhumed on special occasions). In Belize, families bring bodies home from the hospital for a full-day wake and pre-burial preparation, rubbing loved ones in rum to help release rigour mortis-seized limbs more quickly. Closer to home, in Ireland, wakes are held to display the body and queues of people come to pay their respects. In these examples, seeing is believing or at minimum the rituals enhance our understand of our place in the cycle; and it encourages a sense of purpose to help us grieve in meaningful ways.

‘Doulas want to bring death back into the community,’ says Emma, ‘we want to get to a point where people have basic knowledge around death.’

Community seems ultimately the key to unlocking our peace with the end. There is a hunger for open spaces for process and grief – you need only to look at the success of Death Café, which, since starting in an East London basement in 2011, has seen 10,000 events take place in 85 countries.

‘My late son, John, had the idea of Death Café because of his spiritual beliefs,’ says Susan Barsky Reid, his mother and co-founder. ‘He was a devout Buddhist, and so examined death and dying daily. I think he thought it would be helpful for people because there is so much death denial around.’

Indeed, From Here To Eternity concludes that the key to a calmer approach to the end comes as a collective. ‘Death avoidance,’ Caitlin explains, ‘is not an individual failing, but rather a cultural one. Facing death is not for the faint-hearted; it is far too challenging to expect that each citizen will do so on his or her own.’ And Susan points to joy in this shared challenge. ‘My first experience of a death café was life affirming; people laughed a lot and it was very fun. There was such a feeling of intimacy that one got from being with a group of strangers for an hour and a half.’

And then there’s that final link: nature. ‘One of the reasons I’ve been set up to be comfortable with death is because of nature,’ says Emma, ‘because all of nature is constant life and death, and in fact the things we think are most beautiful in nature ultimately tend to be death – like the autumn leaves falling from trees. All of the things we appreciate in nature are only possible because of that cycle from life to death, and I think the more time you spend being really present in nature, the more you feel like part of it, and that normalises being part of the cycle.’

What To Do Next

- Read… Dr Kathryn Mannix’s palliative care memoir, With the End In Mind.

- Attend… A local death café – they take place all over the country (deathcafe.com).

- Consider… How you might like to be buried – and talk about it with loved ones – even if you think it’s a while off!

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

‘My life will be short. So on the days I can, I really live’

— 30 dying people explain what really matters

Facing death, these people found a clarity about how to live

‘I don’t sweat the small stuff any more’

Mari Isdale, 40, Greater Manchester, England

In 2015, Isdale, then 31, was diagnosed with stage four bowel cancer and given 18 months to live. Despite a period of remission and 170 rounds of chemotherapy, the disease has since spread to her lymph nodes.

I always thought, “I’ll get my career sorted, then we’ll get married, have children, go travelling.” And then cancer happened. You grieve for your future self. Your imagined children and your career. If I died tomorrow, what I’d be saying on my deathbed is I regret not spending enough time with my family. So that’s what I focus on.

I have a “Yolo list” of things I want to experience in life and my husband and family work very hard to ensure we do as many of them as possible together. They’ve taken me snorkelling in the Maldives, hot-air ballooning over Cappadocia and snowmobiling in Iceland. We’ve stayed in a cave hotel, seen the pyramids, the Colosseum, and flown in a helicopter over New York. We’ve hand-fed tigers, taken the Rocky Mountaineer train, been paragliding and seen the tulip fields of Holland.

My life is most likely going to be short, so on my good days, when I’m well enough, I really live. I go out and do anything I want: for a nice meal, to the theatre, cinema or an escape room.

My illness has changed the way I prioritise things. Although I loved my career as a doctor, it often meant long hours, missing out on Christmases and birthdays, exams, stress. Giving that up is a big sacrifice, but it’s one I’m willing to make to gain more time with my loved ones. It is ironic that it took being told I was dying before I really started living.

Anything that doesn’t make my heart sing is less important to me these days. I don’t sweat the small stuff any more. Life is too short for cleaning. The laundry pile will wait. And if I want to eat a piece of cake, I damn well do.

‘Don’t waste energy fighting’

Michèle Bowley, 57, Basel-Stadt, Switzerland

After Bowley found a lump in her armpit in summer 2020, a biopsy revealed breast cancer. The disease spread to her lungs, liver and bones, and in late 2021 she was given a prognosis of three to six months.

Accept yourself and your situation. Don’t waste energy fighting. The most important things in life are other people. Pay attention to your needs and do what makes you happy. Do something creative, learn something new, get involved in something that matters to you. Enjoy your life to the last breath.

I have no regrets. I’ve always done what was important to me and have reached my full potential regardless of what others expected or thought of me. I’ve had a fulfilled life; I’m ready to go.

‘Having a sense of purpose brings joy’

Mark Edmondson, 41, Sussex, England

In 2017, Edmondson was diagnosed with colon cancer. After doctors also discovered more than 30 tumours in his liver, he was given a year to live. He has since undergone more than 140 rounds of chemotherapy and over 30 operations.

Prior to getting cancer, I had ambitions of becoming a managing director or CEO; I wanted to achieve something in my career. Within hours of the diagnosis, that disappeared. I don’t care for work any more, but I believe strongly in having a sense of purpose, something to motivate and distract you, and bring joy and satisfaction. I get that from the business I started: a support service for anyone facing adversity. If someone had said, two years into my treatment, “Do you feel able to support other people through their diagnosis?”, I would have said no way. But as time has passed I do, and I’ve spoken to more than 100 people. I love coaching and mentoring. I’ve never been happier.

I lead every session with this quote and loop back to it at the end: “It’s not what happens to us, but how we react that defines who we are.” So how do you want to be defined? Cancer or no cancer, that question should dictate how you live.

I’m a big believer in being as honest and open as possible. Men are notoriously bad at sharing our feelings, but I want to change that for my boys.

We get pushed along in this world by consumerism, but it doesn’t matter what car or house we have, as long as we’re comfortable. What really matters is love, relationships, kindness, caring for people, being around people. I want to create the best relationships I can, and live the happiest life I can, because I no longer know what my timeframe is.

‘It’s not about the quantity of time I’ve got, it’s the quality’

Chris Johnson, 44, Tyne and Wear, England

In 2019, Johnson was diagnosed with a rare gastrointestinal cancer. In 2020, hundreds of small tumours found on his liver led to a prognosis of two to five years.

I’ve got limited time, so I’d rather be doing things with family and friends, and having a positive impact on the world around me. I’m not in the office wearing a shirt and tie any more. In 2021 I was running marathons, and last year I completed the National Three Peaks Challenge.

Fundraising has been the main driver but exercise also helps with the side-effects of my treatment, though as that progresses, it’s becoming harder to do long distances.

I still care about politics, the climate and my football team, but I don’t get stressed about them any more. It’s not about the quantity of time I’ve got it, it’s the quality.

People talk about beating cancer or winning. I’m never going to beat cancer, it’s not an option. At some point it will kill me. But until then, how I live my life is my version of winning.

‘Cancer sorts out what really matters’

Siobhan O’Sullivan, 49, New South Wales, Australia

After feeling unwell for two weeks, O’Sullivan was diagnosed with ovarian cancer in August 2020. It had already spread beyond her ovaries, and did not respond to chemotherapy.

I have a lot of colleagues and friends around the world, and people have mailed me gifts from every corner of the globe. An English friend flew out to see me for three days; he spent longer in the air than with me. This is the kind of generosity of spirit that people have shown me and it’s been very moving.

Cancer has been extremely effective in sorting out what really matters and what doesn’t. I was always a very busy person, and if I was meeting someone for lunch at 1pm and they strolled in at 1.20, I might have been irritated. Now I’ve realised none of that matters. I would love to have had this insight and these connections without having to go through this cancer bullshit. But I don’t think there’s a shortcut to it.

Siobhan O’Sullivan died on 17 June 2023.

‘Sharing your feelings helps’

Harry Soko, 59, Salima, Malawi

In July 2020 Soko noticed a pain in his right thigh. A year later he was diagnosed with skin cancer, which will significantly shorten his life: a 2014 study at the care centre where he is being treated found only 5% of patients with the condition live more than five years.

Normally we say, “If you are suffering from cancer, the immediate result is death.” So my family accepted it. The community accepted it. When I’m alone or sleeping, it comes to me: “Why am I suffering from cancer? How did I get it?” It takes time to accept. But if you share your feelings with others, you become free. You have no worries.

‘My illness stripped me of my fears’

Juan Reyes, 56, Texas, US

Reyes was diagnosed with ALS in 2015; he’d had symptoms for two years, and the average survival time is three. In the next six months he became a wheelchair user; he has since lost the use of his hands.

I’m very much an introvert, quiet and reserved, and afraid of public speaking. Having to live with ALS has stripped me of many of my fears. I’ve always had a very silly streak with close friends and family, and now I use that as a power, to entertain and educate through comedy.

The first time I did standup was in October 2019, at a fundraiser for ALS I’d organised at a local comedy club. I didn’t intend to do it, but as I was opening the evening, I took a chance. Afterwards I felt incredibly alive.

I also went skydiving six months after diagnosis. The first step out of the aircraft took my breath away. The rush of air was deafening, then I was suspended above the landscape. The serene silence, interrupted by the rustling of the canopy, was life-altering. I’m so glad I experienced this. I’m dying, so what is there to fear?

‘Stop worrying about having a good job or needing a big house’

Caroline Richards, 44, Bridgend, Wales

Her son was 16 months old when, in 2014, a swelling in Richards’s stomach was diagnosed as bowel cancer. She was told that, with successful chemotherapy, she would probably live for two years.

These past nine years have been really good, probably better than if I hadn’t had cancer. Different things became a priority: spending time together rather than worrying about having a good job or thinking you need a big house.

In a way I feel lucky – I could have died when my son was three or four. I feel as if I’m living on borrowed time. But he knows me. He’ll remember me.

‘Find gratitude’

Tyra Wilkinson, 50, Ontario, Canada

A family history of breast cancer meant that when Wilkinson was diagnosed with the disease in 2015, she had already made plans for a mastectomy. Seven years later, the cancer had returned and spread to her spine, making it incurable.

My husband and I had plans for when our kids were grown. We have always said we’d be the most fit grandparents, playing with our grandkids on the ground. Even if I’m alive I won’t be able to be that grandparent, because I’m just not capable of doing that stuff now.

Find the gratitude for what you have because it can always – and will always – get worse. Be grateful for all the things that are going your way right now.

‘Go to the parties. Stay out late’

Amanda Nicole Tam, 23, Quebec, Canada

After noticing symptoms in January 2021, Tam was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) that October – five days before her 21st birthday.

I wish I had gone out more with my friends. I wish I had gone to parties and stayed out late. Living life free-spirited is something I feel I missed out on, and I regret that I didn’t take advantage of that when I was younger. Life is short and you should live it how you want, regardless of what people think. Don’t hold back. Say what you want to say and do what you want to do.

‘Have a goal. Don’t accept defeat’

Mark Hughes, 62, Essex, England

More than 20 years ago, pneumonia led to the discovery of a tumour in Hughes’s lung. Surgery was successful, but the cancer had spread to his lymph nodes. In 2010, a rare form of the disease, which is now terminal, was found in his bones.

It’s about having a goal, a purpose, setting your sights somewhere. I won’t be beaten down or accept defeat. The only way is forward, and there’s always a finishing post I’m aiming for. If you get knocked down, get back up, brush yourself down and go again. That’s what keeps me going.

‘You are enough; you make a difference’

Chanel Hobbs, 53, Virginia, US

At 37, Hobbs found herself unable to run without falling; she was diagnosed with ALS and given a life expectancy of up to five years. She is now dependent on a ventilator and feeding tube.

Before my diagnosis, I was very independent. I prided myself on doing things on my own. But I’ve learned that others really want to assist, and it brings them joy knowing they can make a difference, however small.

I always used to plan every single facet of my life. I wish I had been more spontaneous and done things when they crossed my mind. For example, looking out the window and wanting to go for a walk, but doing housework instead. How I yearn for a walk today. Now I give myself grace. I have learned not to compare myself with others. Find what makes you feel meaningful. Remember: you are enough, you are human, and you make a difference.

‘No matter how you feel, get up, get dressed and get out’

Simon Penwright, 52, Buckinghamshire, England

In the early hours of 24 January 2023, Penwright was woken by an unpleasant taste and smell. Doctors discovered three brain tumours, one covering half of his brain. He was diagnosed with an aggressive form of glioblastoma and given less than 12 months to live.

It would be so easy to wake up in the morning and just lie in bed. I’m not a gym person, but when I’ve done a bit of exercise, I feel fantastic. No matter how you feel, get up, get dressed and get out.

If you’re OK one minute, then have a cardiac arrest and you’re gone the next, your options are taken away. So I guess I’m grateful that I can get organised and make the most of my relationships. I’d take this route every time.

‘I’ve stopped caring what others think’

Sukhy Bahia, 39, London, England

Diagnosed with primary breast cancer in 2019, Bahia was given the all-clear by her oncologist in March 2022. Five months later, she discovered the disease had spread to her bones and her liver.

I’m a single mum. It’s heartbreaking because you think you’ll be around for your kids for a really long time. My daughter is nine and my son is six, and I’m completely transparent with them about my health. I’m hoping to leave things for when I’m not here – birthday, graduation, wedding, new home, new baby cards, and a cookbook of all their favourite recipes. I’m also planning video blogs, giving advice on things they may not be comfortable asking anyone else, like consent and puberty.

I want them to know that they never have to impress anyone or try to fit in, and that milestones are bullshit. Nothing needs to be done by a certain age or time; you can always change what you want to do in life.

I’ve stopped caring what other people think of me. From my teens, I always wanted a full sleeve tattoo. Last year I decided to start one with the birth flowers of my children, to show how much they mean to me.

My kids love them; my parents aren’t over the moon, but they accept there are worse things I could be doing with my life.

‘Never create a new regret’

Kevin Webber, 58, Surrey, England

On holiday in 2014, Webber noticed he was visiting the bathroom a lot. Soon after he was diagnosed with prostate cancer and given four years to live.

I don’t have many regrets. Maybe I wish I’d taken my kids to school more. When they grow up, you realise that meeting you had at work, you could have probably moved it back an hour.

In that moment, when you know it’s over, I don’t want to look back with any remorse. You can’t change yesterday. Never creating a new regret is an important way to live your life.

I have three missions every day. Enjoy myself, but never at the expense of someone else. Try to do some good – and that doesn’t have to be raising 10 grand for charity; it can be smiling or giving someone a seat on the bus. And make the best memories, not just for you on your deathbed, so you can lie there and go, “Oh, that was great when I did that”, but for everyone else.

‘I realised what I really wanted to do’

Sophie Umhofer, 42, Warwickshire, England

In 2018, after 10 months of tests for conditions such as IBS and Crohn’s disease, Umhofer was diagnosed with bowel cancer, which had spread to other parts of her body. She was told she could live for three more years.

Initially I felt as if I had to cram the rest of my life into the couple of years I’d been given. I’ve written birthday cards and letters for my kids until they’re 21, preparing them for me not being here.

Obviously I wish it hadn’t been cancer that caused this, but I’ve changed so many things about myself. Before my diagnosis I would get very stressed out. I had this perfectionism when my kids were young that they had to have routines. I spent so much time being worried about things I didn’t need to do. And once I became a mum, I sort of gave up what I wanted to do.

I regret that I didn’t take action for myself a bit more. But this diagnosis meant that all of a sudden, I realised what I really wanted to do. When I was going through chemo I was trying to find things I could do to keep myself entertained, and I started watching motorsport. When I got a bit better I actually entered a competition and got through to the finals. I ended up getting a job in motorsport and now work full-time looking after a team. I wish everybody could see how much better life can be if we change the way we think.

‘Leave the damn house’

Arabella Proffer, 45, Ohio, US

In 2010, Proffer was diagnosed with myxoid sarcoma. Ten years later, the rare form of cancer was found to have spread to her spine, lungs, kidney and abdomen. Told to get her affairs in order, she now plans her life two months at a time.

A year before I was first diagnosed, my husband had joked, “Hey, why don’t we cash out our retirement and follow Motörhead and the Damned on tour through Europe?” When I got the diagnosis, I thought, “We should have done that.”

My mantra is to leave the damn house, because you never know what’s going to happen if you do. No interesting story ever started with, “I went to bed at 9pm on a Tuesday.”

‘Just buy it. Do it. Go and get it’

James Smith, 39, Hampshire, England

In 2019, Smith noticed a twitch, then a weakness in his left arm. Two years later he was diagnosed with motor neurone disease (MND).

When I was told I’ve probably got only a few years to live, my wife was pregnant with our youngest. In the back of your mind you’re thinking, “Am I going to see them get married? Have kids?”

I did turn to alcohol, but it wasn’t doing me any favours; I was using it to block out what I didn’t want to think about, so I nipped it in the bud. Now I’ve come to terms with what I’ve got and I just take every day as it comes. I focus on what I can do, not what I can’t do. I had to give up my career as a barber, but I’ve found a new passion in creating my podcast, which shares my story and those of others to raise awareness of MND. Talking to others and relating to people going through the same situations as me is like therapy.

It’s horrible to say it takes a terminal illness to actually live life, but when I hear people going, “I’d love to do that”, I realise getting diagnosed has put a different perspective on life. I used to think, “I won’t buy that because I don’t know what’s around the corner.” Now it’s just buy it, just do it. If you want something and can afford it, go and get it. If you want to do something and you’ve got the means, go and do it.

‘I soon realised what I liked about life’

Ali Travis, 34, London, England

At 32, Travis began experiencing severe headaches. After an MRI revealed a mass the size of an orange on his brain, he was told he had a glioblastoma and his life expectancy was 12 to 14 months.

Last year was the best year I’ve had because in a very, very short space of time, I realised what I liked about life. It’s the closeness of relationships, old friendships. And, for me, being a geek.

If I’d been hit by a bus, I’d have been a stressed guy with a load of problems who couldn’t see past the end of his nose. So, despite all the surgeries, the constant chemotherapy, the radiotherapy, I would choose this route.

‘Look after yourself first’

Sonja Crosby, 55, Ontario, Canada

In 2012, doctors discovered a tumour on Crosby’s left kidney. She was diagnosed with a rare form of cancer, and most organs were removed from her left side. In 2017 she was given six months to live.

Cancer focused me more precisely than anything else I can think of. When my doctor told me I had a few months left, I said, “Can we put that off another six months? I have this big project at work I want to finish.” He said, “No, you have to be your priority now, not work.”

You can’t manage all aspects of your life. I’ve realised it’s not selfish to look after yourself first, that your friends and family will do a lot more if they know you’re open to receiving help.

‘My favourite saying is: it is what it is’

Rob Jones, 69, Merseyside, England

In October 2012, Jones was told he had bowel cancer that had spread to his liver. He had 27 rounds of chemotherapy.

I’m not a bucket list person; I don’t go through life saying, “I wish I’d done that.” My wife says I’m one of the worst people in the world to buy anything for, because if I want it, I get it. It’s the same in life, if we can afford it. But I’ve never had dreams of doing a world cruise or a flight to America. I’m a home bird really.

I read once that cancer victims are lucky in life, because they generally have a timeframe of when they’re going to die. They can put their life in order, say goodbye to loved ones, ignore all the people they’ve tolerated to be polite. Whereas people who have a massive heart attack and die on the spot, they don’t have that opportunity. I sort of get that now. But I’m not allowed to talk as if the end of the world is nigh, because everybody thinks I’m invincible. Of course, none of us are.

My favourite saying is: it is what it is. If we had the choice, we’d all live a long, happy life. But when would we choose to die? There isn’t a convenient time.

Rob Jones died on 28 July 2023.

‘What’s the point of earning, earning, earning, if there’s no joy in your life?’

Jules Fielder, 39, East Sussex, England

In November 2021, Fielder was diagnosed with double lung cancer, then shortly after told the disease had spread to her spine and both sides of her pelvis.

You get caught up in that world of work: pay your bills, eat dinner, sleep, repeat. But now I truly feel very different about money. What’s the point of earning, earning, earning if there’s no joy in your life? When I watch really power-driven people who want more and more, I want to tell them it’s the small things in life that are beautiful. We live in quite a toxic world, but it’s your choice what you expose yourself to. Iget up, I walk my dog, I listen to every single bird that chirps. I’m grateful for that.

‘Be authentically you’

Mike Sumner, 40, Yorkshire, England

While on TV show First Dates in March 2020, Sumner noticed a loss of movement in his foot. Eight months later he was diagnosed with motor neurone disease. He has since married his date, Zoe.

I don’t waste time now. Life is too short to be doing any shit you don’t want to. Concentrate on making the memories you want and never say no, never make excuses. Do things you’ve always wanted to do. We went to Los Angeles to see the Back to the Future set at Universal Studios. I’ve been meaning to go for years. It was our little pilgrimage.

In the short term I keep positive by thinking about weekends, because we often go away and do something fun – next weekend we are going to a classic car show. In the longer term, I look forward to our next holiday – we always go to Orlando. When I feel the warm air on my skin, and hear the crickets of an evening, it lifts me emotionally.

Day-to-day I look forward to Zoe coming home from work so I can give her a cuddle. I look at my model car collection and think about the happy memories I have of driving. When I feel a bit low, I treat myself to something nice to eat – pizza, a burger or a battered haddock – while I can still enjoy food.

You have to be authentically you. But try not to moan because there’s always someone worse off than you. Focus on the positives; there are always some. For example, I’m married to Zoe.

‘Keep things simple’

Alec Steele, 82, Angus, Scotland

In 2020, while in hospital for a routine checkup, Steele collapsed. Tests revealed idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis – which causes scarring on the lungs and leads to difficulty breathing – and he was given a prognosis of one to five years. He now requires a 24-hour oxygen supply.

The first six months after diagnosis were dreadful. I was trying to get all my affairs in order, and I told my medical team I was determined to have one last game of cricket. The physiotherapist and I worked as hard as we could, and in late April 2021 I got my game, wicketkeeping with oxygen strapped to my back. A photographer took a photo and put it on the internet. It is now displayed at the Oval, next to Ben Stokes’s photo. Last year I had 16 games, which has just been wonderful.

I’ve realised I have to keep things as simple as possible. I soon learned that negative thoughts were destructive and I trained my mind to work out those you can do something about and those you can’t. If it’s the latter, discard them. If you can do something, work out what and get started to tackle the problem.

‘Switch every negative to a positive’

Kate Enell, 31, Merseyside, England

In July 2021, less than a month after finding a lump in her breast, Enell, then 28, was diagnosed with stage four breast cancer. It had spread to her liver and bones, and has since moved to her brain.

For two days after being diagnosed I locked myself in the bedroom; I didn’t see or speak to anyone. But on the third day I thought, “Wait – if I’ve only got a short timescale, do I really want my little boy to see me miserable?” Now I just try to do as much as I can while I’m here. I’m quite good at switching my brain now. Say I get upset about not being able to have more children, I switch it round and think, “Well, I am a mum.” Whenever there’s a negative, I try to switch it and keep positive.

I feel like I’ve had some of my best times in the first few years of my diagnosis, because it makes you home in on what’s important. Everybody around me has made more of an effort, we’ve done lots of family events. It’s made us realise that what’s important is spending quality time together.

‘Success, status, reputation – they are not important’

Ian Flatt, 58, Yorkshire, England

Flatt had always led a very active life, but in April 2018 he began struggling with severe fatigue. By the following March he had been diagnosed with MND and he has since lost the use of his legs.

I can categorically say that the things I valued and felt were important are not important. Success, status, reputation – they pay the mortgage, but I think I lost myself a little bit in all that. I’m much more emotional and empathic now. I’ve always been a reasonably popular guy, I have friends that go back 30-odd years, but I’ve never had the depth of friendship that I have now. Or maybe I had it and didn’t appreciate it.

What’s important now, every day, is to find some joy. I look out at the birds, the trees – I’ve a favourite one I can see out of my bedroom window. Through being a bit reckless, I lost the use of my legs sooner than I would have. I remember accepting that and thinking, “OK, I’m not going to walk, so let’s go out in the tangerine dream machine [his off-road wheelchair].” We went out, had a pint of Guinness, and now my memory of that day is a joyful one.

‘Your energy is valuable’

Daniel Nicewonger, 55, Pennsylvania, US

In May 2016, after he started struggling to take a full breath, Nicewonger was told he had colon cancer that had spread to his liver. The prognosis was two years.

It took this to clarify what’s really important. You get very good at saying, “No, I choose not to invest energy and time in this, because my energy and my time is just that much more valuable.” If I could have understood that at 30, I’d have moved through life in a totally different way. But that’s unrealistic. Wisdom is wasted on the young.

‘Don’t mess around. Be direct’

Angus Pratt, 65, British Columbia, Canada

A lump on Pratt’s chest in 2018 led to the discovery of breast and lung cancer. He was given a 5% chance of living to 2023.

I had my diagnosis in May, my wife was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer at the start of October, and by the middle of November she was dead. I had to ask myself the big question: am I leaving behind what I want to leave behind?

I’ve taken on writing assignments, helping scientists translate research into patient-friendly language. Recently I was asked to contribute a painting to an auction, and I was surprised people would pay for my art. One of my joys is a local poetry group that meets in the park. Sometimes we have an open mic. I guess I’m trying to say I’m a poet, too.

I’ve discovered self-confidence. I really don’t care what people think about me any more; it’s not important because I’m going to die. I don’t have time to mess around, so I’m going to be direct. That’s stood me in good stead.

‘I should have trusted myself more’

Henriette van den Broek, 63, Gelderland, the Netherlands

When Van den Brook was diagnosed with breast cancer in 2008, the disease had already spread to her lymph nodes. She was well for a number of years, but in 2020 she discovered that the cancer had spread to her stomach and was terminal.

Every day when I work as a nurse, it feels like a party for me. I realise how meaningful I can still be to other sick people. I enjoy the little things more, dare to have the difficult conversations.

It’s a pity I’m only finding that out now. I feel like I need to catch up on this in a hurry and get the most out of life. I’m discovering the things I’m good at, but I’d have liked to discover them sooner. I should have trusted myself a lot more and been less insecure. I only have the guts now.

‘Treat every smile like it’s your last’

Ricky Marques, 42, St Helier, Jersey

In summer 2022, Marques began to lose weight. In November, a CT scan led to a diagnosis of lung cancer. The disease, which has spread to his bones and lymph nodes, was so advanced that he was given a prognosis of weeks or months.

When I was younger I had a son, and when he was eight, he died in a car accident. My life collapsed and I thought, “How am I going to recover?” When I was diagnosed with terminal cancer I thought, “What else am I going to get? Didn’t I already have my share of bad luck? Don’t I deserve to live?”

The lesson I’ve learned is every time someone smiles at you – a little touch, a little gesture – look at it like it’s the last one because, guess what? Maybe it is.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

My 2024 Goal Is To Have A Good Death

(But not this year)

By Ryvyn

American culture is extraordinarily goal-oriented. This January, pause and notice the messages and expectations that are motivating you. Everyone creates goals regarding all aspects of life. In a single day, we set a vast number of goals to accomplish.

Adults have daily, monthly, or yearly goals for their job which may not be in alignment with their additional career goals. Athletes have intense levels of goal achievement and mindset work. Others may have spiritual or emotional goals. You might also have social, educational or even comfort goals, for instance, you want to purchase your own car or house or you want to start a family or gain independence. This list of goals can go on ad infinitum, but you have gotten the point by now and I’m beginning to feel overwhelmed by just listing possible goals.

Thus, I began polling people about their goals. I recently had a conversation with an acquaintance who stated their goal for 2024 was to add days to their family vacation. And then I sat there waiting in silence until it became uncomfortable, and I realized that was all they were going to say. I found myself in awe. I did not know what to say or how to respond as my mind whirled out of control with the list of goals I had set just because it’s TODAY and tomorrow isn’t promised!

My mind thought of my weightlifting, cardio, yoga, nutrition and meditation goals, the stack of books I plan to read, the podcast episodes and blog articles I want to do, the networking organizations and business researching, and any new certifications I think will benefit myself or my staff. Every year I want to see an increase in business profits. This breaks down to clients, social media and marketing goals, community outreach, pro-bono work.

As a member of my religion’s clergy, I have personal spiritual preparation and educational goals. Then there are relationships, family, and travel goals. And, underlying it all, my goal is to just handle what I’ve got scheduled and NOT take on any other GOALS!!!

I realized making New Year’s Goals is passe when I attended a business networking group recently, the host asked, “For those of you that are still into it, raise your hand if you’ve set goals for 2024?” Only about a third of the people raised their hand.

As a 2023 volunteer service goal, I committed to hosting monthly, virtual, Death Cafe meetings. For more information go to DeathCafe, According to the Death Cafe rules for these meetings, the only requirement is not to have a plan or agenda and to simply to hold space for the conversation. These are often sacred and sincere moments where people are vulnerable and share their thoughts and experiences. That required a personal commitment to do so. I see goals as personal commitments for growth, if you are not growing and learning you are stagnating.

One of my yoga certifications is in Brain Longevity Therapy Training. One of the tenets to a healthy aging brain is to keep it active. Activities like learning new skills, reading, socializing, movement work like balance and exercise all affect the brain. The brain and body need to be challenged to keep them working at optimal levels. However, growth is often a process that occurs even during dying and all the way through death. I often look at death, not only as transition but as an initiation. Death is an unknown and it takes preparation to face it in peace. Physician-assisted suicide, or “medical aid in dying”, is legal in eleven jurisdictions, the Commonwealth of Virginia is not one of them. As a Death Doula, I have been bedside with several people as they were actively dying. Some are aware and some are not, while all these deaths were medically regarded as peaceful. I do not know that they would classify as a “good death” if it were my own.

Holding space for Death is a growth experience. My ultimate goal is to have a good death and all my other goals reflect that. No, I am not actively dying, I am actively living. I am acutely aware of the fact that tomorrow is not promised and that gives the simplest of moments a glamor that most people do not see.

For example, walking my very elderly dog is its own growth experience in mindfulness. We walk slowly and methodically. Her eyes are not as clear now and it is obvious she has become mostly deaf. She avoids stairs or steep hills. She demands pets from any stranger and wants to sniff any friendly dog. She takes long pauses to sniff thoroughly between bushes and under benches. I have time to notice the clarity of the stars above and watch the diamonds of frost begin to form as we stand silently on the abandoned sidewalks in the winter darkness. The sweeping mantle of cold (or possibly arthritic joints) makes her knees tremble slightly.

We slowly walk along, allowing her to go as far as she wants and where she wants, until she spontaneously turns around and heads back. Some days she stands in the doorway to our apartment looking through as if she has forgotten where she is, cautious about entering. Other days, as she sleeps long and deeply, I will hear her whimper and look over to see her feet moving slightly, clearly dreaming of running and playing with other dogs or her humans. I know time is growing shorter for her, but we will face that together. I do not ever want her to feel alone or unloved. We can never accurately predict when a natural death will occur, so you must be ready all the time. Ushering a pet is much like a person. We sit and just be with each other. Sometimes I talk but other times it is just not needed. She just wants someone to be present and touch her. So much is conveyed through touch.

Time seems to shrink for elders. One activity, like a medical appointment or meeting a friend for coffee, can be exhausting. You think you have all the time in the world to accomplish the things you want but knowing Death can come at any time can make the experiences of life taste even more sweet. I do not like to repeat experiences, travel to the same places or even eat in the same restaurants because I might miss an opportunity! When I die, I want to know I lived my life to its fullest and took every opportunity to suck the life out of every single minute. This requires commitment, planning and setting goals.

Take a minute to consider if you knew you only had one year left to live. How would you live differently? What would take importance? Do you have the cash? Make it happen. Set those goals! Say the things that need to be said! Do the things you need to do! Heal the things that need attention! Let go of the past and be present! It’s time to outgrow your comfortable life and move into the adventure of living fully so that when Death arrives you are ready to take that journey with her without hesitation or regret weighing you down.

P.S. I offer a virtual Death Cafe meeting every month, for more information google “Death Cafe of Southside Virginia” or look us up on DeathCafe.com

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Not a Bad Day to Die

— In the midst of feeling so alive on a beautiful day, why do thoughts of death creep in?

By Jane Adams

Movies at midday are one of the pleasures of aging; the theaters aren’t crowded, the tickets are cheaper, and later you can fill up on happy hour hors d’oeuvres and skip dinner.

I was headed for a matinee on a balmy, blue sky spring day a few weeks after a recent decade-changing birthday. Passing a flower market on the corner, I bent my head to the profusion of peonies clustered in tin buckets, breathing in their deep, rich scent. All at once I was literally set back on my heels by a thought that had never once occurred to me before, a thought so fully formed that it sounded like a voice in my head: This wouldn’t be a bad day to die.

“But sometimes we have an awakening experience, like realizing in a particular moment of contentment or completion that today wouldn’t be a bad day to die. It seems to be a message from the deepest part of the self that is always aware of the fact that we’re mortal.”

The censor that pushes the unthinkable back into the unconscious must have been asleep at the wheel. Why this, why now? I wondered. Why, in the midst of feeling so fully alive — so healthy, happy and untroubled — was I suddenly struck by the notion of my own death?

“If you don’t think about dying once a day or more – including doing the math when you read the obituaries – you’re in denial.”

I’ve lost friends and family members to death, but it’s only lately that I’ve thought much about my own. It’s not a preoccupation or obsession — not yet — but it’s increasingly taking up space in my head. The friends I was meeting at the theater agreed that, at our age, “If you don’t think about dying once a day or more — including doing the math when you read the obituaries — you’re in denial.”

Unexpected Thoughts About Death

That consciousness of our mortality happens in unexpected ways at ordinary moments. Death may not be imminent, at least not as far as we know, but it’s not unthinkable, either. Some of our closest friends and relatives have already died, and others may be in declining heath or facing a terminal illness.

Our own death is a subject we can talk or think about for only a brief time before we’re submerged in sadness, overcome with fear or frozen in disbelief. Yet daring to confront it frees us to fully engage in our own lives and those of the people we love until the last minute. That’s the existential telegram we don’t always see coming, the real message from the unconscious: Life itself is a terminal diagnosis.

Perhaps you or someone you love has received a more immediate one. The one unexpected gift of living with such news is dying with it; it’s an opportunity to examine your life and make meaning of it, finish your unfinished business, express your regrets, make your amends and renew your bonds with those you love.

Of course, you don’t have to be dying to do those things. In fact, the sooner you do them, the better: None of us knows when death will come or how we will experience it. We may plan for it, to the extent that we can, and in fact we must. We may hope for a long, slow gentle death with time to say goodbye before surrendering, or perhaps a lucky one, something so quick we never see it coming or suffer the grief of those we leave behind.

The good news is that facing up to death reconnects us to the richness of living as fully in the moment as we can for as long as we can.

The more we know about death, the less there is to fear it. We may approach it in small chunks, or from different perspectives, but we can’t put it at the safe distance it used to be. The good news is that facing up to death reconnects us to the richness of living as fully in the moment as we can for as long as we can.

The deaths of friends or acquaintances bring me closer to thinking about my own. Right now, I believe I want to have a “conscious” death, free from pain but not awareness. When the time comes, though, I may change my mind; I thought I wanted a natural, unmedicated childbirth, too! Because I live in a state that has legislated compassionate choice, I have the right, whether or not I have the opportunity, to decide when and how I die.

Until then, though, even the most thorough planning and foresight are not cure-alls for coping with the eventual reality of not being, the terror at the end of the self. “Anxiety is the price we pay for self-awareness; staring into death renders life more poignant, more precious, more vital,” as psychoanalyst Irving Yalom writes: “Such an approach to death leads to instruction about life.”

An Awakening Experience

We may be too involved in the prosaic quality of our everyday lives to let that terror out of the place we’ve corralled it — in our nightmares, in the depths of the unconscious, in the assurances of faith that another, better existence awaits us in the kingdom of heaven. Or we may have stored it in the mental compartment where we’ve contemplated our ultimate end, analyzed and even reasoned with it, and wrestled it to the ground on which we base our beliefs and values.

But sometimes we have an awakening experience, like realizing in a particular moment of contentment or completion — a garden planted, a goal accomplished, a conflict resolved, a problem solved, a question answered, or even a burden lifted — that today wouldn’t be a bad day to die. It seems to be a message from the deepest part of the self that is always aware of the fact that we’re mortal.

I wake up in the morning – and sometimes, lately, after an afternoon nap – pleased and surprised that I’m still here.

The message stimulates us to let go of ambitions and desires whose wanting drains the pleasure out of what we’ve already acquired or accomplished. Our imagination may still take us to places and experiences that thrill us to consider, but it may be wiser now to look at our bucket list one last time, cross off what’s not important any more, and stop fretting about what often still bugs us; getting to the bottom of it, carrying a grudge, caring what strangers think of us, going places we don’t want to go, being with people we really don’t like, doing things we no longer enjoy, and especially, saving things for later.

My own bucket list in this autumn of my life is divided into two columns: “Still Theoretically Possible” and “Very Long Shot.” What’s on the former are a winter in the Caribbean, finishing my memoirs, getting a tattoo, and finding a man who drives at night. On the latter are going around the world, falling in love or even lust again, winning the lottery, and having Oprah choose my still unwritten novel for her book club.

I do not long for death, or await it, as Mary Oliver writes, wondering if I have made something particular and real of my life. I am fortunate in having family and friends who reassure me that I have, and words, written and spoken, that have made a positive difference in the lives of others I will never meet.

I wake up in the morning – and sometimes, lately, after an afternoon nap – pleased and surprised that I’m still here. I believe in the conservation of energy, and that when I die, mine will be absorbed into a cosmic consciousness I’m certain exists outside of time.

If I’m wrong, of course, I’ll never know. And that’s a comfort too. And meanwhile, I’ll stop and smell the peonies.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

The Palliative Path

— A meditation on dignity and comfort in the last days of a parent’s life

By Abeer Hoque

In 2020, in the midst of a worldwide pandemic, my 85-year-old father suffered a heart attack in Pittsburgh and was rushed to the hospital.

The stent, a minorly invasive procedure, was the easy part.

But the two days he spent in UMPC’s state-of-the-art ICU were a nightmare. The anesthesia made him groggy and aggressive. The sleep meds made him perversely restless and short of breath. The IV he constantly fiddled with, once even ripping it out, much to our horror.

Instead of restraining him, which I imagine to be a cruel and unusual punishment for an Alzheimer’s patient, the ICU staff let me stay with him overnight (a massive kindness made greater by the strict Covid protocols of that time). This way, I could keep him from wandering, from pulling out the IV, from being confused about where and why and what. Every two minutes—I timed it, and it was comically on the clock—I explained and comforted and explained again. By midnight, I thought I would go mad with worry and exhaustion. By 3 a.m., I was seeing stars, my father and I afloat in an endless hallucinatory universe of the now. By 6 a.m., we were both catatonic.

After he came home, my father was in a bad state. Physically he was fine, if a bit unsteady, but emotionally, he was depressed, anxious, raging, unresponsive. His appetite was out of control and he raided the fridge at all hours. He barely slept, wandering the house like a ghost of himself. It took almost three months for him to return to his ‘normal’—another immense gift from the universe, as medical crises often spell inexorable decline for the elderly.

A year later, the doctors discovered a giant (painless) aneurysm in his stomach, which could rupture and kill him “at any moment”.

Operating would mean a five-inch incision, at least five days in the ICU and up to a year to recover fully (if at all). For someone with dementia, major surgery also seemed a cruel and unusual punishment. From New York to Philadelphia to Pittsburgh, my siblings, my mother and I met over video chat to discuss at length. We made the difficult decision to let the aneurysm be, to keep my father comfortable and at home.

Initially, my mother felt tortured. Were we giving up on my father? Was she abdicating her responsibility?

These are questions that modern medicine is not always fully equipped to answer.

Doctors (especially surgeons) are often focused on finding and fixing the physical problem. But Alzheimer’s is a uniquely mental condition and it forced us to consider my father’s health and well-being on more than just the physical front. We wanted to prioritise his dignity, his comfort, his pain-free state: namely, his overall quality of life.

Days later, the doctors told us that the aneurysm was actually inoperable because of its position in his body. Moreover, there were two rogue blood clots that, if disturbed, could travel to the brain and kill him instantly. Our decision had been the right one, not just mentally but also medically.

Our family made another big decision at this time: we would not take my father to the hospital anymore—instead we would start palliative care.

I have been recommending Atul Gawande’s brilliant book Being Mortal to everyone since I read it five years ago. It lays out the case for palliative medicine (a.k.a. hospice care) in compelling detail. Instead of trying to prolong life, palliative care prioritises a patient’s physical and mental well-being and focuses on pain management. Not only does this kind of care drastically reduce the chances of family members developing major depressive disorder, but the patient outcomes are astonishing:

Those who saw a palliative care specialist stopped chemotherapy sooner, entered hospice far earlier, experienced less suffering at the end of their lives—and they lived 25% longer. If end-of-life discussions were an experimental drug, the FDA would approve it.

Atul Gawande, in his book ‘Being Mortal’

In February 2023, my parents moved to Dhaka after 54 years abroad (in Libya, Nigeria and the States), abandoning the isolating, exorbitant, often neglectful care networks of America for the familial support and affordable at-home caregiving of Bangladesh. We were privileged to have this option, to have extended family so loving and helpful, to have enough money to pay rent and hire multiple caregivers.

For my mother, who had been my father’s full-time caregiver for over a decade, it was a new lease on life, letting her visit childhood friends, walk in Ramna Park every morning, get a full night’s sleep. We were additionally lucky that over 10 months, we did not have to see a doctor because my father’s occasional tummy upsets and falls did not result in serious illness or injury.

In December 2023, my mother left for the US for five weeks to visit my sister and her three children and to hold her newest month-old grandchild (my brother’s first child) in her arms. It would be the first time in more than a decade that she would leave my father for more than a few days, and she agreed to this vacation only because I had taken an extended break from my life in New York to be in Dhaka while she was away.

Three days after she landed in Pennsylvania, my father suffered his first medical crisis in over a year: a distended belly and extreme stomach pain.

I immediately called my cousins who live down the street. Two of them brought over their mother’s doctor, a young generalist who worked in the ICU of the hospital around the corner from us in Bonosri. Seeing my father’s taut and grossly swollen stomach, the doctor advised urgent hospitalisation. Thus started a gruelling, repetitive, exhausting conversation about palliative care, all while my father cried out in pain from the bedroom.

Despite several palliative and hospice centres in Dhaka, the concept seems unknown to many Bangladeshis, perhaps even heartless.

Neither of my cousins could sleep that night after hearing my father’s cries. I explained why we had decided against hospitalisation, against X-rays, ultrasounds and blood tests, against antibiotics and IV-administered fluids. I predicted that the hospital would likely have to restrain or sedate him or both. I said that even if we eased his physical state, mentally he would be traumatised.

This resistance to palliative care is not uniquely Bangladeshi. Families across the world are torn apart because family members have different ideas on how to best take care of a loved one. Too often, no one has asked the patient their preferences about resuscitation, intubation, mechanical ventilation, antibiotics and intravenous feeding. Too often, it’s too late to ask by the time these medical interventions come into play.

The doctor finally offered pain and gastric medicine via intravenous injections. One bruised wrist later, my father was more comfortable. Over the next 24 hours, he had two more injections, but by the third one, the pain meds were no longer working.

At 2 a.m. on a cool Dhaka winter night, we levelled up, the doctor generously taking time off his night shift to come to our house with a nurse and administer an opioid that eased the pain for another day and half.

By Christmas, or Boro Din as they call it in Bangladesh, I had defended palliative care more than half a dozen times to my relatives, each one aghast at how my father could suffer so, without my helping, i.e., hospitalising him.

This then was my struggle: to remember I was not there to fix anything, but to ensure that he remain in familiar surroundings, in his sunny airy bedroom. That he not be in pain.

This too was my struggle: to get my extended family on board with palliative care.

The cousin who came to live with us in America when he was in high school and who idolised my parents. The cousin who asked me to bring my father’s nice shirts and blazers from Pittsburgh so he could wear them. Their sweet wives, my bhabis, and their lively loving children who visited my father almost every day. To hold back my kneejerk reactions:

Are they questioning my family’s judgement? Is this the patriarchy at work? Do they understand that it is no easier for me to see my father in pain?

My challenge was to set my defensiveness aside and try to infuse their love and concern with knowledge and perspective, so they could help me help my father spend his remaining days in comparative ease, rather than more aggressive medical treatment.

My last struggle was the hardest of all: The one that questioned the kind of life my father had been living these last few years.

Nine years after his Alzheimer’s diagnosis, he could not do a single thing that used to bring him pleasure: dressing nicely each morning, making himself breakfast while exclaiming over the newspaper headlines, reading history books and novels, writing fiction in Bangla, teaching geology in English, wandering the Ekushay February book fair, visiting his ancestral home in Barahipur, playing cards and watching action films, making his grandchildren collapse into giggles, walking on the deck at sunset with Amma, holding court with the Bangladeshi community in Pittsburgh, speaking to his two beloved remaining siblings, my Mujib-chacha and Hasina-fupu, delighting my mother with his quick-witted jokes.

If he could make no new memories and the only joys he had were fleeting—the chocolate chip cookies from Shumi’s Hotcakes, my mother’s smiling face, his caregivers’ tender ministrations—were these enough?

Was there some Zen-level lesson here on living in the moment?

And when these brief moments were interleaved with longer troubling periods of confusion, distress, rage and sadness… What then?

What about the endless hours spent restless and awake, his eyes lost and searching?

My father and I had had a fraught relationship my whole life.

Patriarchal and emotionally distant, he threw me out on several occasions, literally and figuratively. I didn’t speak to him for years at a time, and even reconciled, our exchanges were limited to politics, education and writing. He seemed uninterested in anyone’s emotional life, unable to engage in conflict without judgement and anger. His gifts of intellectual brilliance, iron-clad willpower and moon-shot ambitions did not make him an easy father—or easy husband, for that matter.

But now, none of that mattered. The only thing that did was my attempt to attend to him with kindness.

Linking his dementia-fueled rage to his life-long habitual rage would make the already difficult task of caregiving impossible. I had read enough studies that showed that caregivers died earlier because of their stress. It wasn’t hard to see the toll it had taken on my mother over the years. She had been hospitalised for rapid heartbeat issues twice last year and, despite a lifetime of healthy living, had developed high blood pressure to boot.

In his sleep-deprived, pain-addled state, my father didn’t always respond or recognise those around him. But one night, in a moment of lucidity, he reached for my hand and asked urgently, “Are you doing ok?”

“Yes Abbu,” I assured him, “I’m doing fine.”

And then he said—faint, incomplete, clear—“Take… your Amma.”

I said, “Of course I will.”

He was telling me what I’d always known, that despite everything, he had always looked out for my health and self-sufficiency, and more importantly, that looking after my mother was our shared act of service.

If this winter of struggle and sorrow gave my mother more time in the world, then I was ready for it. Would that the path were palliative for us all.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!