— For Maggie we chose a sunny day and roast chicken

Our dog Maggie died on Tuesday, just shy of her 15th birthday. Last February, our vet said we’d be lucky to get Mags through winter. That it would be her last trip around the sun. Nobody told our old warrior. Stubborn and tough as nails, she ploughed on. Until she didn’t.

A month ago, at the vet surgery, three of us crouched over Maggie, focused on her pale gums. “Super anaemic,” said Dr Lissi. Blood tests, a suspected tumour, an ultrasound, no real answers. Just the knowledge now our girl really was close to the end.

There was a reason she suddenly wanted to sleep outside all night, that her truckloads of drugs were harder to juggle and leaving her agitated. Arthritic, she struggled to stand.

“She’s really tired,” said Lissi, a specialist in end-of-life care for pets. Her worry was Maggie was on the brink of a catastrophic event like an internal bleed. “She’s had a beautiful life. We want her to have a good death.”

A good death. Sheesh. On paper, the intersection of loss and dignity. For us, a crushing responsibility, of agreeing to a day for Maggie to slip earthly ties, noting it down like a lunch appointment. Surreal.

We chose a day when the forecast was sunny, so she could go with warm fur. Maggie ate roast chicken. Had her blue leather collar taken off for the last time. “Learn To Fly” was playing. Lissi arrived.

Edith Wharton called dogs “the heartbeat at your feet”. We had the terrible honour of cuddling Maggie as her own warrior heartbeat stopped. She chose the spot: her corner of my home office, in front of the bar fridge.

A good death.

Chris and I wrapped her in a blanket, spooned her, told her she was our North Star. A metronomic swimmer, really good player of balloon tennis, but hater of hot air balloons. We carried her to the vet van, shut the doors. Opened them again for another kiss.

Then she was gone.

Since then, we’ve dehydrated ourselves so much with weeping we’re looking like old apple cores. Exhausted, we prop up in bed at 7.30pm for the sweet torture of Maggie photos and videos. We’ve remembered the time she stuck her jaws together with a stolen wheel of Brie, the day she ran onto Alexandra Parade rather than face her groomer.

And we kept all of her stuff right where it was. Bed next to ours. Blanket unwashed. Unfinished packet of beef straps in the laundry. I’m carrying around hair clipped from her fringe in a Glad Bag. What I don’t know what to do with is the grief.

While nobody has dared say “she was only a pet”, we know she was a pet. We know our friends Sam and Steve have lost their dads John and Ian at the same time, and that this is not a shared tragedy like losing a child, partner or parent.

Still, missing an old dog has made me feel like I need to go to hospital. She was our shadow, in every room with us every day. The backing track to our fights, laughter, lives.

Is it normal to feel this unhinged? Sick of being told to “stay strong” and – kill me now – “fur babies are family”, I’ve turned to science.

There’s more research than you’d think about losing a pet. PubMed has 96 papers for the search term “grieving pet”. One says mourning the loss of a pet needs recognition from health systems. A 2019 study published by the US National Institutes of Health says a pet’s death can take longer to get over than a person’s.

There’s also the pre-emptive fear another pet, current or future, will cause the same heartache.

“Those who do insist on a special relationship with their dog or cat put themselves at risk from a mental health point of view,” wrote UK psychiatrist Kenneth Keddie in a 1977 study, one of the first about pet mourning.

Magsy, I’d lose my marbles a million times for you. Sleep tight, beloved beautiful girl.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

I’m A Death Doula

— How Death Makes Me View “Imperfections” Differently

By Alua Arthur

When I’m called to a bedside, my clients and their families often believe that I know every single thing there is to know about death and dying. But despite the countless hours I have spent with people as they prepare for death, there are many things I will never understand.

Who could? Certainly not the scientists, philosophers, or sidewalk preachers among us. They are all still alive. The near-death-experience people? They got to the lobby of death and turned right back around. Death doulas like me? We’re still alive too. I can read all the books and get close to death a thousand times over, but without experiencing it firsthand, I’m just as curious and clueless as the next living person.

What I have observed from the deathbeds of others is that dying is a process of transformation of the body, and death marks the end of that transformation. When our time on earth is up, our bodies turn from vibrant, connected vessels animated by something unknown into lifeless, empty matter in the space of a single breath.

Bodies tell our story. At the end of our lives, they give away clues about the type of life we lived. My clients’ faces often reveal how they moved through the world.

For example, Jonathan’s deep furrows in the middle of his brow suggested skepticism and inquisitiveness. He had been an astronomer, and the only bit of flooring visible in his home was the path from his living room to his bedroom. The rest was covered in stacks of glossy science magazines. He stubbornly refused his reading glasses to read them. His constant squinting was visible in his face, even when it was at rest.

A former dancer named Elizabeth, bedbound for three years after multiple knee and hip replacements, had deep smile lines around her mouth with a matching pair around her eyes, stretching upward into her temples and toward the sun. They told of exuberant joy in her life. Even in her final weeks alive, she giggled like she was falling in love.

Frowns, disapproval, and sadness sat in Ernst’s jowls. At a diminutive 4 feet 8 inches in height, he was as crotchety as old men come, only allowing me to visit because his daughters insisted. He seemed to delight exclusively in his grandson’s obsession with trains, which he also shared.

Ernst constantly looked like there was rotting fish in the room unless his grandson was around. Edward’s upper arms, torso, and thighs were covered in tattoos. He was a big-time corporate lawyer who headed up a motorcycle club in the suburbs where he lived. He left his calves and forearms un-inked because of golf vacations with the associates at his firm.

And then there’s my body. I hope that when I die, my body says that I danced, enjoyed the warmth of the sun on my face, and loved both squats and french fries.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

How a mysterious illness broke apart a family

— In “Forces of Nature,” Gina DeMillo Wagner writes about growing up in the shadow of her brother’s illness.

by Courtney Tenz

Death is on our minds. Four years into a pandemic that killed millions and left little room for collective mourning, it feels as though we remain in a long season of grief. That sentiment is reflected in the glut of recent memoirs that grapple with bereavement, as if many writers had spent their days in isolation reflecting on what else they had lost. Among them is Gina DeMillo Wagner, who captures the complexity of grieving a sibling in “Forces of Nature: A Memoir of Family, Loss, and Finding Home,” a moving recollection of growing up with a brother with a disability and absent parents.

Wagner’s elder brother, Alan, who died in 2016 at the age of 43, had been diagnosed as a child with Prader-Willi syndrome, a rare genetic disease that affects metabolism and behavior. Although his body grew to reflect his age, Alan’s psychological development slowed during the siblings’ childhood in Atlanta, leaving him almost entirely dependent on others. Though little was known about the disease during Alan’s childhood, symptoms of his illness were evident throughout his life. Sweeping in unpredictably, those symptoms overwhelmed Wagner’s mother, a housewife. Though it is impossible to diagnose exactly what lies behind a divorce, it is easy to imagine that the weight of Alan’s illness proved too much for his parents to bear together. Their split, which resulted in the absence of the author’s father and a yawning emotional gap from her mother, runs through Wagner’s life like a fault line.

“The forces that create faults are compression, movement, expansion, and gravity,” she writes, employing a metaphor that recurs in the book. “Whenever something is under pressure, weighted down, vibrating, or grating against itself, trying to move in opposite directions — things crack. Fractures occur. Destruction. New geographies are formed.”

The new family geography that arose after the split found Gina taking on the household responsibilities to fill in for the parental lack. Alan was prone to overeating and volatile moods (people with Prader-Willi prove nearly insatiable and lack impulse control), and Gina, in her telling, often found herself on the receiving end of his destructive rage. We cannot always recognize trauma while we are living through it, and you get the feeling that, long after the fact, Wagner is hesitant to call what she lived through traumatic even as she relives harrowing scenes on the page. It may be in part because of the nature of Alan’s illness; childlike on his best days but swelling with extra-human strength when enraged, he could not be held fully responsible for the pain he inflicted on his sister.

>She does not fault him for the volatility his disability created, instead looking to the natural world to draw parallels, especially the creation of the Rocky Mountains, a region she now calls home. “I think about the core attributes of a person, their own personal bedrock,” she writes. “Their personalities, their fundamental traits seem solid unless acted upon dramatically by some outside force.” In Alan’s case, that external pressure was from the patrilineally heritable disease. For Wagner herself, the outside forces are numerous: her brother’s rage, her mother’s neglect, a school counselor who recognizes that something is wrong in the family. When the pressure eventually exerts itself too intensely, Wagner decides to leave her family before even finishing high school, estranging herself for decades to gain control over her life.

All this time later, there’s a palpable melancholia as Wagner works through her brother’s death and the process of mourning a person she loved dearly, despite the injury and anguish he caused her. “No one talks about what grief looks like when the relationship you lost was fraught,” she writes. “No one admits that a relationship with someone who is dead can be just as complicated as the relationship was when they were alive. There was suffering then, and there is suffering now.”

With a tinge of survivor’s guilt, Wagner ruminates on Alan’s last days, seemingly looking to ensure that her absence from his life did not, in a roundabout way, end it. Yet it’s hard to know what assurances might assuage her. Wagner is reluctant to accept the explanation that doctors give her of natural causes, a reluctance matching the uncertainty that relatives of those with rare diseases face when so little is known about their loved one’s medical condition.

Ultimately, instead of finding greater answers to Alan’s death, Wagner lands in the uncomfortable position of having to confront the complicated choices she made in removing herself from the family: “The deeper question is not whether Alan could have survived longer, but how did I survive all those years?”

It’s a question that readers themselves might ask as Wagner retells the story of her childhood from the vantage point of an adult reuniting with her family for her brother’s funeral. Faced with her parents in the same space again, she finds herself navigating new family fault lines. Vacillating between reflective adult observations and recollections from youth, she also reckons with her present: Could she have created a happy family of her own had the mother of a high school friend not witnessed her pain and taken her in as a teenager, providing a path for escape?

The memoir thus becomes a lovely meditation on how families are formed within hostile landscapes. Wagner is a talented stylist, limited only by an inability to explain the inexplicable — in this case, less her brother’s rare disease than her parents’ behavior. She contemplates what might have been had her mother accepted more responsibility, had her father taken a greater role in their upbringing. “Maybe his death was no one’s fault,” she writes. “Just as the abuse was never our fault, his or mine.”

In the end, this is not a story of what-ifs but rather what-nows. With the earthshaking news of Alan’s death, the shape of Wagner’s life becomes clearer — in her metaphor, it is like a landscape, which “forms a complete picture, even with its holes and valleys and rifts and green and blue debris.” From above, she writes, you can make sense of it in a way impossible on the ground. It’s this bird’s-eye perspective that provides Wagner and her readers some much-needed closure.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Death doulas help people navigate end-of-life.

— Death doulas help people navigate end-of-life. “I say we work in the in-between.”

By Renee Wilde

David Copeland remembers his great grandmother’s death.

“She died with all of us around her, singing to her, and that’s how she slipped away from here,” he said. “And I want to slip away the same way.”

Copeland is the owner of Live Without Regrets. He works as a death doula guiding others through the end-of-life.

Only 36% of Americans have written or talked to loved ones about their end-of-life plans, according to the National Funeral Directors Association. Yet, everyone will have the experience of dying.

“I say we work in the in-between. In between life and death. In between joy and sorrow. We work in between questions and answers. We’re navigating that.”

Having these difficult conversations, and coming to terms with our impermanence can be scary, sad, and mysterious, and it provokes anxiety for many.

“I say we work in the in-between. In between life and death. In between joy and sorrow. We work in between questions and answers. We’re navigating that,” Copeland said.

“If I can be, I try to be present for the death and the transition,” he said. “If you want a vigil, if you want somebody to stand next to you, if you want songs or singing, and all the things that come with vigiling.”

Copeland also helps the dying navigate conversations with friends and family, and examine the kinds of legacy they want to leave behind.

“Sometimes it’s writing letters to friends, or writing letters to kids that may not be in your life. You’re estranged, but this is what they wanted to give you when they passed – here you go, directions,” he said. “And it’s just good for people to take control of that part of their dying experience and the life they lived.”

Even medical professionals, whose jobs require delivering difficult news, can struggle to talk with their patients about dying. So part of Copeland’s role as a death doula is working with the dying to help them understand what’s going on.

“We have the ability to have real conversations,” Copeland said, giving an example. “Alright, they say you have pancreatic cancer and have six weeks (to live). Well what does that mean? What to expect? Some folks want that to know that so they can prepare, some people don’t. They don’t know how to have those conversations with the health care system. “

Copeland is also an advocate for the LGBTQIA+ community, who have unique needs that often require them to not only grapple with death, but also dignity and identity.

“You have aging trans people who go back in the closet when they go inside of hospice centers and nursing homes because they won’t be able to keep themselves,” he said. “I really push for them to have a representation for disposition of the body. It helps so that the next of kin don’t come in and do whatever they want to you, and dead name you and misgender you and do all the things that you didn’t want.”

Michael Kammer said the five important things family and friends can say to a loved one who is dying are: I love you, I forgive you, forgive me, I’m going to miss you, and goodbye.

Michael Kammer, a former medical social worker at Hospice of Dayton, has guided many people through the end-of-life. With his unique background as a former chaplain, massage therapist, and social worker, he has helped the dying navigate the mind, body and spirit.

Kammer said that when people come into hospice sometimes it’s already too late to have these conversations.

“The patient comes in and is unresponsive, so we are working with the family. But, of course, it’s still important for the family to communicate with the patient, even when the patient can’t communicate back,” Kammer said. “Because we all believe in hospice care that they hear, that the patient hears and at some level understands.”

Kammer said the five important things family and friends can say to a loved one who is dying are: I love you, I forgive you, forgive me, I’m going to miss you, and goodbye.

He said he would also add a sixth: that it’s OK to let go.

“It’s amazing to see how when just the right person gets there and has that conversation with the person who is dying, they’re often able to slip away, sometimes very quickly,” Kammer said.

Like Copeland, Kammer’s work with the dying has led him to come to terms with his own mortality. “Well, for one thing I no longer fear my death. I’ve imagined my death in every imaginable way possible.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

There’s Something I Have Been Dying to Tell You

The title for this article is taken from an autobiography from Linda Bellingham, an actress who wrote about her experience of living with terminal cancer: the difficult and at times awkward feelings and sense of taboo that comes from facing one’s death. It is this taboo that drew me to write this piece.

By Jack Timmins

The inevitability of death is exactly why it should be discussed.

It is natural to avoid thinking about dying, particularly for young people. If you are young and healthy, why do you need to think about dying anyway? It is normal to put it to the back of your mind, and if you do think about it, to presume it will be a good death – one where you die peacefully, surrounded by loved ones and a pain-free and gentle end to a long, happy life. It can be, and for some people it will be. But this is not a guarantee. The inevitability of death is exactly why it should be discussed. To live your best life, it is important to consider your best death, and one of the ways to ensure a good death is the principle of assisted dying.

You are probably familiar with euthanasia but perhaps not with assisted dying. Maybe you think it is the same thing? The distinction between euthanasia and assisted dying is that the former is a deliberate act to end a person’s life for them, whereas the latter enables them to do it themselves. For example, euthanasia is like a doctor turning off someone’s life support machine, while assisted dying is providing a dying relative access to a lethal dose of medication. Both practices are currently illegal in UK law.

However, in March this year, Liam McArthur, a Liberal Democrat MP, tabled the Assisted Dying for Terminally Ill Adults Bill, which he expects to be debated in Autumn this year. This bill would make it legal for eligible adults to be provided with assistance to lawfully end their own life. However, it would only apply to those living in Scotland. It is worth noting that assisted dying is legal in Switzerland, the Netherlands, Canada, Australia, and several US states. A recent poll from a campaign organization, Dignity in Dying, revealed that 75% of the public supports assisted dying, with only 14% opposing.

It is time to stop assuming that everyone wants to stay alive whatever the cost, and do what we can to ensure people can have a good death.

One of the concerns is that if the law were to change, rather than giving vulnerable people – those in pain or with long-term conditions – more autonomy and control over their bodies, it could have the opposite effect. It might add a sense of pressure on them to die, to remove their burden. There are also safeguarding concerns that the law could be exploited to coerce people into killing themselves, particularly women.

Fundamentally, assisted dying concerns only one thing – autonomy. It gives people the right to make their own choices. It is not about an obligation or justification for suicide, rather, it is about taking an honest, candid approach to one’s health. The reality is that there are people currently in terrible situations without any chance of getting better. They know this, and they understand this and decide that this is not the future that they want. However, they are forced to endure it because they have no choice. They are met with various arguments like life is precious, and that their symptoms can be managed. But if the pain is unbearable, surely it is more humane to respect their choices than reduce their symptoms and suffering.

As people are living longer, what was once a taboo, uncomfortable topic of conversation is now being rightfully discussed. Much like how cancer was once stigmatized and referred to as ‘the Big C’, it is time to stop assuming that everyone wants to stay alive whatever the cost, and do what we can to ensure people can have a good death. It is the responsibility of any modern state.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

A chosen end to a ‘wonderful life’

— Cancer patient on why she opted for an assisted death

By Mariné Lourens

Tracy Hickman has lived her life “pedal to the floor” – just existing has never been an option. So in less than two weeks, she’ll have an assisted death. Mariné Lourens reports.

>Sitting across from me on her couch, Tracy Hickman looks cosy in a warm woolly sweater with a blanket tucked around her legs. She is strikingly intelligent and every so often, despite the weighty topic of our conversation, an infectious smile flashes across her face.

It feels quite surreal to know that in two weeks, Tracy will be dead.

On May 22 to be exact. On a beach, surrounded by loved ones with the sound of the waves in her ears, she will breathe her last breath. “I can’t think of a better way to go,” she says.

The 57-year-old Auckland woman’s bubbly personality makes it hard to fathom the extent of the disease wreaking havoc inside her body.

It started with a routine mammogram in March 2019 which detected a malignant tumour in her left breast. Within two hours a doctor was talking to her about a mastectomy and the possibility of chemotherapy.

“It was so confronting. Two hours after a standard mammogram I was sitting there talking to this doctor about mastectomies without anyone there to support me.”

She was diagnosed with HER2-positive breast cancer, a form of cancer that tends to be more aggressive than other types. A left-side mastectomy was done, followed by 12 weeks of chemotherapy treatment.

Hickman had to take some time off from her job as director for Chartered Accounting firm Baker Tilly Staples Rodway during her treatment, but returned to work part-time in August 2019.

In December 2019, her other breast was also removed, both as a preventative measure and to achieve symmetry.

For all intents and purposes, the treatment had been a success. There was no evidence of cancer cells and Tracy focused on getting back to life as normal. For her this included continuing to run some of the most challenging marathons in the world – she has completed the six World Marathon Majors, a marathon in Antarctica, and a 250km ultramarathon in the Sahara desert called the Marathon Des Sables.

“But I never felt free of [the cancer]. I always thought it was going to come back,” says Tracy. It wasn’t something she could attribute to physical symptoms, just a gut feeling that this chapter of her life was not quite over.

An unwelcome return

In October 2021, Tracy was watching television with her long-time partner, Paul Qualtrough, when she noticed numbness on one side of her face and the fingers on her left hand. “My first thought was: ‘Is the cancer back?’”

A brain scan didn’t show any abnormalities, but a month later it happened again. Another brain scan was done, but again showed nothing of concern.

A neurologist said it was likely a type of migraine. Tracy was dubious, but her concerns that the symptoms might be related to her previous cancer diagnoses were shut down.

Then the seizures started. The first one was on a Sunday in November 2022, while Tracy and Paul were at a farmers market close to their home in Grey Lynn in Auckland.

“I suddenly couldn’t speak. I couldn’t form sentences and I was numb down my side. Paul called Healthline and they said it could be a stroke, take her to ED,” says Tracy. “They did a CT scan, they said the CT scan doesn’t show anything. We’ve looked at all her notes, it’s a migraine.”

It was only in February 2023 when a seizure happened in the presence of a neurophysio that Tracy’s oncologist was finally notified.

An MRI of her back showed two tumours, and a subsequent PET scan showed more tumours in her lungs, chest wall, lymph nodes and numerous more in her spine.

“When all of this was happening, it was the cancer. It was not a migraine, it was cancer and it was just not being picked up.”

The cancer spread quickly. “A scan showed that between February and April, it got really bad. They started talking about me possibly not making it to Christmas.”

Tracy was terminally ill, but there was treatment available to try and give her more time, maybe even up to eight years.

After she had suffered significant side effects with her previous cancer treatment, Tracy was torn between fighting for more time, or declining the treatment and just making the most of whatever time she had left. She decided to give the treatment a go.

Fighting for time

More rounds of “really harsh” chemotherapy made her lose another 20% of her hearing – she was already wearing hearing aids after losing a significant amount of hearing to the chemotherapy in 2019.

The cancer treatment also caused nerve damage resulting in incontinence. “That was maybe one of the hardest things to deal with. I was in a shop buying a gift for a friend and I thought, oh, someone’s baby needs changing. And when I got home, I realised it was me and I didn’t even feel that I had been.”

Immunotherapy gave her terrible diarrhoea, a particularly difficult side-effect to deal with when you’re incontinent. She had terrible “chemo brain”, a mental fogginess that made it difficult to concentrate, think and make decisions.

On top of it all was the pain. Intolerable, unshiftable pain. She was prescribed morphine for the pain, but hated how “out of it” it made her feel.

“I said to my oncologist I don’t want to have treatment any more, I want to stop.”

Tracy knew this meant any chance of extra time was dashed, but life had become unbearable.

From about June last year, she started looking into ways to take her own life. “Even though I thought I had another two or three years left, I didn’t think I could do two or three years. I didn’t know if I could keep going until Christmas this year.”

In March she made one last trip to the UK to say goodbye to dear friends. She knew it was going to be her last long-haul trip.

It turns out she didn’t have two or three more years. Far from it.

Upon her return to New Zealand, a scan showed over 30 tumours in her brain. “They stopped counting at 30.”

There were more tumours in her lungs and spine. Her sternum was broken due to the cancer making her bones weak and now every breath was accompanied by a stab of pain.

Tracy had about three months left to live, maybe less. She was eligible for assisted dying.

The End of Life Choice Act 2019, which became legal in New Zealand in November 2021, means only those suffering from a terminal illness that is likely to end their life within six months are eligible for assisted dying.

Tracy picked a date. It had to be on a day that nobody close to her had a birthday, far away enough for her to get everything done she still wanted to do, but close enough that she would still be competent to make and communicate an informed choice on the day.

She decided on May 22.

Goodbyes

Tracy’s sister, Linda Clarke, came over to New Zealand with her husband and daughter to spend as much time with Tracy as possible.

Tracy and Paul booked a weekend to Sydney where she said goodbye to some friends, a few days in Queenstown where she took a helicopter trip to the top of a glacier, and a trip to Rotorua where she supported some of her running friends taking part in a marathon.

“I’ve had so many dinners and lunches and things. Some I knew that was going to be the last time I was going to see them, so I said goodbye. Others I knew I would be seeing them again. I have a whole list of when I am going to see people and what I’m doing and who I am saying goodbye to.”

She is making the most of the time she has left – “I’ve had so much chocolate in the last month!” – but she’s ready. Her ability to swallow has already decreased and is expected to get worse. “With the pain and the incontinence and everything else, I am ready to go.”

Paul supported Tracy’s decision from the moment it was made, but admits seeing an actual date on the calendar – and especially seeing how close it was – was immensely painful.

He fights back tears as he explains why a decision so incredibly difficult was also the right one for them. “All you can ever do in life is play the hand you’re dealt and look at the choices available and take those that you think are going to lead to the best outcome. And this is the choice that is going to lead to the best outcome. It is a lot to get your head around… But this, for us, fits.”

There have been a lot of tears. Sometimes one comforts the other and sometimes they cry together.

“Most nights I wake up around 2 or 3 o’clock in the morning and I have a little cry,” says Tracy, but during the goodbyes, in keeping with her caring nature, it is usually Tracy comforting others.

Linda Clarke says a life without her sister is unimaginable, but she supports her in having a choice over her own death. “I don’t want to lose her and I shouldn’t be losing her. But having this time to say goodbye is a pure gift, even though it is a very hard one.”

She describes Tracy’s last few weeks as an “emotional rollercoaster”, filled with get-togethers with friends and doing fun things, but many painful goodbyes.

Tracy says it is a privilege to be able to choose an assisted death and she feels fortunate to live in a country where that is a possibility. “I can’t do the things I love any more. I can’t work any more, I can’t travel any more and I can’t run any more. I feel like I am not me any more. So the people that I love aren’t with the person that they know and love, and for all of those reasons, life has become unbearable.”

She believes when the legislation is reviewed, it should be expanded to allow people who could truly benefit from it to also have that choice over their own death. “My form of illness is almost what was in mind when the legislation was written, but in actual fact, there are many people out there who could benefit from an assisted death, but are not eligible. Someone who has eight months or 10 months, might end up having a really horrible death because they are not eligible for assisted dying.”

She is not scared of dying, nor is she angry about her fate. “It’s happened, you know, and it’s better it happened to me than someone with little children or someone really young.”

Getting some treatment that will allow her to be around a bit longer but suffering through unbearable pain was not worth it. “Just existing is not how I live my life. I’ve always had the pedal to the floor and done everything I could possibly do. I’ve had a wonderful life,” she says.

“Everyone who knows me has said, ‘you just seem so at peace now’. And I am. I am at peace.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Dying and Other Stuff

— A Practical Perspective on Good Deaths

Death is considered taboo in the Western world and many other cultures. With the world’s population aging rapidly, we cannot afford to turn a blind eye toward the process of dying. We owe it to ourselves and our loved ones to advocate for the tools, knowledge and spaces necessary to prepare for a good death.

At the age of 87, my father passed away from cancer in Calgary, Canada. He had multiple myeloma, an illness that made his bones very fragile. He was bedridden for the last nine months of his life. Instead of hospice, he wanted to spend his remaining time at home for several reasons. We could be with him 24/7; he could be in familiar surroundings, eat his favorite foods and watch his favorite shows; and we could retain control over his care and manage it according to his wishes.

My mother, sister and I supported his decision. My 80-year-old mother managed the home and cooking. I scheduled appointments and managed his day-to-day care. Since this was during the COVID pandemic, my sister could work from home and would pop up between meetings to feed him. My sister and I would alternate doing night duty. It was the best of times; it was the worst of times. It brought us all closer; it was frightening and exhausting.

In the final days, I felt myself woefully unprepared to guide a loved one through this inevitable journey in a gentle and reassuring manner. I wondered why our society and culture do not offer us more support. Death needs to be made into a less traumatic and more normalized process.

We are woefully underprepared…

Globally, the population is aging; the number of people over 80 is expected to increase dramatically from 137 million in 2017 to 909 million by 2100. In Canada, more than 20% of the population is over the age of 65. In the US, that number is approaching 18%.

Some 61 million people the world over died in 2023. That number is expected to reach 120 million annually by the end of this century. The upcoming decades will see the steepest rise in the number of annual deaths in possibly all of our human history. Death should be an important public health topic — both globally and nationally.&

For the experience of birth, there is an abundance of support and enthusiasm. There are informational books like the classics What to Expect When You’re Expecting and Pregnancy, Childbirth, and the Newborn and Ina May’s Guide to Childbirth. More are published each year. Prenatal classes are found in numerous hospitals and community centers. Some stores cater specifically to new parents, offering necessary as well as cute items. There are celebrations like baby showers. Grandmothers and mothers and aunts and sisters and friends share their excitement, wisdom and help. There are hospitals and obstetricians. And there are doulas and midwives.

For the experience of death, we are sad, frightened and alone. There’s not enough support, even though experiencing death — either others’ or even our own — is as much a part of our existence as birth. In fact, one could argue that death is the more universal experience. Yes, we’re all born, but we don’t even remember it later. In contrast, many of us are even conscious and coherent in our final days before death. Apparently, just before he died, Oscar Wilde had the wherewithal to say, “Either that wallpaper goes or I do.” While not all of us give birth, we all die. We need to be better prepared for death.

…but we don’t have to be

We don’t do too badly in terms of books on the subject of death. While there’s not yet a What to Expect When You’re Dying, there are several excellent books on the practical aspects of death: Atul Gawande’s Being Mortal; Sherwin Nuland’s How We Die; Margaret Rice’s A Good Death; Katy Butler’s The Art of Dying Well; and Sallie Tisdale’s Advice for Future Corpses. Such books can help to introduce, inform and normalize the concept. They can help us see death not just as something to avoid, but as something to prepare for.

There are no classes on how to die well, but there could be. Just like how we have prenatal classes, we could offer pre-death — or to be parallelly Latin, “premortem” — classes, for anyone experiencing death. Premortem classes would be taken when we know death is impending, or even beforehand to motivate us to make the most of our remaining time. To make them accessible, these classes could be offered in hospitals and community centers just like prenatal classes.

True, death means the loss of a person instead of a gain. But isn’t that even more of a reason to have a celebration before dying, to appreciate what is precious while we still have it? There is rarely a pre-death celebration, particularly in the West. End-of-life celebrations can bring the dying and their loved ones together to reminisce, reaffirm and say goodbye. In some communities in South India, the 60th and the 80th birthdays have long been celebrated with special fanfare. There is a puja (prayer) for the guest of honor, followed by a feast and party attended by a large number of family and friends. The Western world is now thinking of “living funerals” — or the happier term, “celebrations of life.” Perhaps we should embrace them wholeheartedly.

Preparation for death could also involve a bit of a shopping-and-social experience. There are already “Death Cafés” where people meet in a café to talk about death. There is potential to expand this to a full-time, accessible space with books on philosophy, faith, how to have a good death and how to guide loved ones through the process. There could be support group meetings for the dying as well as their companions. Conversation groups on a variety of death-related topics and lectures from experts could offer those premortem classes. Given the growing demand foreseen over the course of this century, this has the scope to develop into a purposeful space for preparing for death.

Professional care shouldn’t end at the hospital

While bookstores and cafes can offer space to talk about death, there is still a demand for experts to coach us through the process. There are palliative care doctors, but only in cases of incurable diseases and not for cases of regular deaths. Hospices are few in number and are only open to those with a terminal illness and a prognosis of less than six months. As a society, we need to consider and plan spaces where people — especially those who are alone — can die in comfort and with easy access to professional expert care.

Over the past 20-some years in the US, the percentage of deaths at hospitals has decreased from 48% to 35.1%. The percentage of deaths at home has increased from 22.7% to 31.4%. In a 2013 survey in Canada, 75% said they would prefer to die at home. Governments too prefer to have us pass away at home, as it lessens the burden on nations’ hospitals and healthcare systems. Passing away at home may be what most of us want — in a familiar place, surrounded by our memories and family. How nice it would be if we could also have a death expert on hand. Just as we have a midwife to assist us in the birthing process, we could have a midwife to help us in the dying process. Surprisingly, such people exist.

A death midwife or doula is simply defined as a person who assists in the dying process. There are already death midwife associations in several countries (e.g., Canada, US, UK), such as the International End-of-Life Doula Association (INELDA). Death midwives can perform a variety of services. Many provide information and logistical assistance, such as death planning and funeral planning.

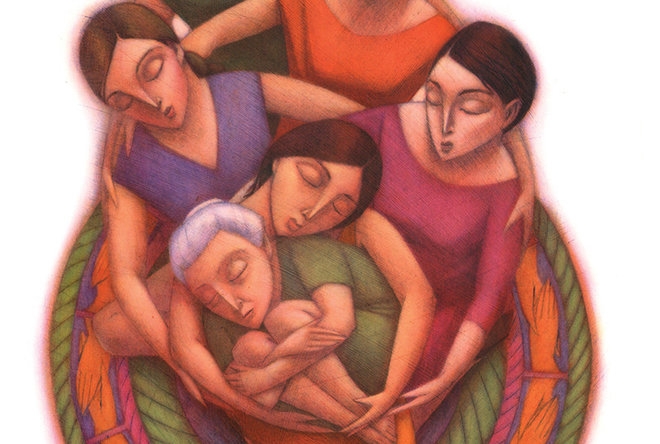

I envision a broader and more intimate role. I see a death midwife as similar to a birth midwife, someone who is very hands-on and who has a link with a doctor. A comforting, compassionate and yet objective presence who has helped many die well. It would involve assisting with physical as well as emotional end-of-life care. Just as the birth midwife helps both the mother and the child, I see the death midwife as helping both the dying and their companions. Death midwives can give guidance in accordance with the wishes of the family and, most importantly, in accordance with the wishes of the dying. They can hold our hand till the gate.

We owe it to ourselves

Given the unprecedented numbers that will be dying in the coming decades, it would be wise for societies at large to treat death as a public health issue. And given that none of us is likely to escape death, it behooves us individually to advocate for support systems – such as informative literature, preparatory classes, conversation groups, dedicated products and spaces, and accessible death experts and midwives. A good death may well be possible if we prepare to evolve in such a manner. We owe it to our parents, ourselves and to our children.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!