She doesn’t want her estranged family to attend. I want to respect her wishes, but am not sure the excluded family members will.

My wife and I have been together for 30 years. Five years ago, she started dialysis, and that same year her mother’s divorce from my wife’s stepfather was finalized. Like many divorces, it pretty much split up the family.

My wife’s health is declining rapidly now, and she was also denied placement on the transplant list due to other health issues. We have been discussing her death, and my wife has expressed that she does not want her ex-stepfather or two of her siblings to attend her funeral.

When my wife made her wishes known to her mother, her mother said that my wife’s ex-stepfather has every right to attend the funeral because he raised her since she was about 8 years old, and that the two siblings also have every right to be at her funeral because they’re her brother and sister.

My wife explained that she did not want them at her funeral, because of how her ex-stepfather treated her when she was growing up and because the two siblings sided with him during the divorce. But her mother reiterated that she wouldn’t do anything to stop these people from attending the funeral.

I told my wife that the only way to make sure her wishes are met is to not tell her family about her passing until after she has been laid to rest. My wife agreed that this may be the only solution. Is this the right course to take?

Louis

San Antonio, Texas

Dear Louis,

I’m so sorry that your wife is ill, and I can only imagine that the prospect of her wishes not being met adds substantially to the stress you’re experiencing. But what seems to be getting lost in the understandable turmoil is that your wife is still here, which means she has agency over how she interacts with these people before the funeral happens.

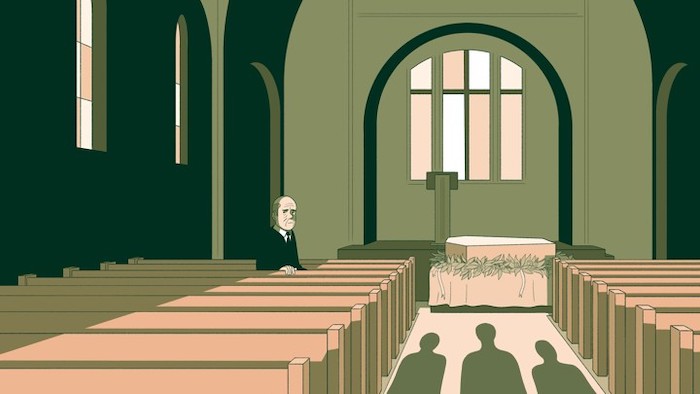

Let’s back up for a minute. What’s complicated about funerals is that not everyone agrees on whom they’re for. Are funerals for the dying, comforted by the knowledge that they’ll be surrounded by friends and family when laid to rest? Or are funerals for the living, a chance to grieve in the company of others and get one final goodbye? Whose comfort and peace of mind are funerals for?

It sounds like you and your wife believe that funerals are for the person who died, and therefore this person should determine before her death who will be there. And it sounds like your mother-in-law believes that funerals are for the living, and therefore that your wife’s ex-stepfather and siblings will want to be there. You probably won’t resolve this philosophical difference—though understanding it may help you to be more compassionate toward your mother-in-law’s view—but you do agree on one thing: These family members mean to attend the funeral.

The question is, why? You don’t say what these relationships are like now—whether your wife is on speaking terms with these relatives; whether they know about her prognosis; whether they’ve shown any concern for her; whether, perhaps, you’ve kept your wife’s condition from them so they haven’t had an opportunity to share their concern. Nor do you say how your wife was mistreated growing up, or whether her mom has acknowledged the extent of the mistreatment. Maybe your wife spoke with her mom about her wishes because she’s no longer in contact with these relatives, but by not communicating with them directly, she puts herself in a position of powerlessness, which may be how she felt growing up and again during the divorce.

Banning people from a funeral is both a personal request and a strong public statement. At least in part, it’s a declaration to all who attend that these people hurt your wife deeply, and in this way, her pain would finally be acknowledged. This is what her wish is fundamentally about: a way for her to deal with the pain of the past.

Quite clearly, though, there’s a catch. If banning them from the funeral represents a final, public acknowledgment of her pain, the one person who needs that acknowledgment most won’t be alive to see it. So maybe it’s worth considering what might bring your wife even more peace than their absence at her funeral: the opportunity to be heard by them now. In my therapy practice, I’ve seen people with terminal illnesses spend the time they have left in different ways. Some people don’t change much—they hold on to their anger and resentments and die with them firmly in place. Others step far outside their comfort zone and grow tremendously in ways that feel immensely gratifying.

I don’t know which route your wife will choose, but here’s an option for her to consider. Instead of saying to her family members, essentially, “I’m angry with you and I get the last word!” (because by the time they learn about the funeral they missed, she’ll already be gone), she might say, “I’m angry with you, and I’d like to understand more about what happened between us before I die.”

She may learn that these relatives don’t realize how much they hurt her; or that they feel bad for having hurt her; or that they feel hurt by her, and there’s another side of the story she hadn’t been willing to consider before—her own role in the family drama. If that’s the case, there might be room for compassion on all sides, and while compassion won’t erase what happened in the past, it might pave the way for a greater understanding that allows a connection to find its way into their lives. And that small change can be potentially transformative, especially at this time in her life.

Of course, just because your wife does something differently doesn’t mean other people will. If they’re not willing to consider your wife’s point of view (remember, they don’t have to agree with it), if they place all the blame on her or are rude or insulting in these conversations, your wife can take a different tack. She can say she believes that the time to show respect is while a person is still alive, and if they can’t show her respect in life, it would be disingenuous of them to pretend to “pay respects” when she’s dead. For this reason, it would upset her to have them at her funeral, and if they genuinely want to pay respects, they can do so by respecting her preference for that day to go as she wishes.

They may say fine. Or they may still insist on coming, in which case she can ask them point-blank, “Why are you insisting on coming to a funeral for someone whose feelings you don’t care about and who doesn’t want you there?” Just hearing the stark truth in this way may encourage them to reconsider.

But here’s the thing: No matter what happens, your wife will have gotten to say her piece while she still can. Whether you have a private service or they attend her funeral, it won’t matter as much as the fact that she was proactive and forthright, spoke her truth directly to the people involved, and took control of what she had control over—how she wanted to live in a way that expressed her self-worth. Some people go their entire lives and never give themselves this opportunity. She doesn’t have to be one of them.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!