By Michael Upchurch

[I]n a beautiful passage, early on in her new book, Haitian-American author Edwidge Danticat explains, “We write about the dead to make sense of our losses, to become less haunted, to turn ghosts into words, to transform an absence into language.”

Danticat’s own masterpieces — her memoir of her father’s and uncle’s deaths, “Brother, I’m Dying”; her novel-in-stories about a Haitian torturer, “The Dew Breaker”; and her early collection of tales, “Krik? Krak!” — have done exactly that. Her prose is often cool and taut on the surface, yet also rife with hidden currents and flashes of warmth. At her best, Danticat taps into such tough subject matter as political exile, mob violence, and refugee desperation with a trickless, spellbinding clarity.

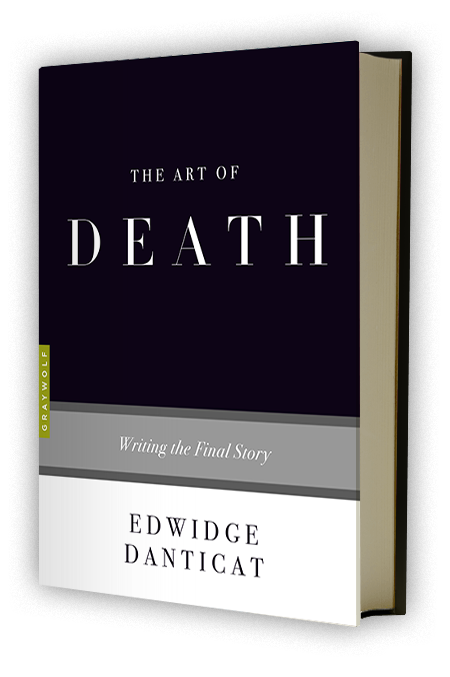

The strongest thread in “The Art of Death: Writing the Final Story” (one in a series of Graywolf Press titles addressing specific aspects of the craft of writing) is her account of her mother’s reaction to being diagnosed with stage 4 ovarian cancer.

“In the car on the way home,” Danticat remembers, “we were both lost in a terrible silence that should have been filled with tears. At a red light, where I stopped for too long, my mother spoke up for the first time since we’d heard the news and warned, ‘Don’t suddenly become a zombie.’ She was telling me not to lose my good sense, to keep my head on my shoulders.”

Her mother brought humor even to the most humiliating hospital situations. To a nurse who had trouble drawing blood from her, she wisecracked, “It’s too bad you’re not like those vampires on TV who just put their teeth on someone’s neck.” When, toward the end, she opted out of repeated rounds of chemotherapy, she couldn’t have been more straightforward about it. “I’m not necessarily dying either today or tomorrow,” she said. “But we all must die someday.”

Danticat’s portrait of her is kind and loving. It also is, inevitably, anguished in its sense of loss. “I was shocked,” she says, “by how quickly many others expected me to bounce back and rejoin the world.”

But “The Art of Death” isn’t simply a memoir. It looks at how other authors have dealt with death in their writing. Danticat’s focus is on Tolstoy, Camus, Chekhov, Gabriel García Márquez, Toni Morrison, Audre Lorde and more than three dozen others. She touches on her own work as well.

It’s an impossible task, and Danticat’s attempts to order her thoughts on suicide, bereavement, and death-row prisoners’ experience can be unwieldy. She’s less assured when analyzing someone else’s text than she is when evoking her own experience. Her extensive commentary on Morrison’s novels, for instance, can’t compete with Danticat’s direct dealings with death.

Danticat is a straight shooter as a writer, so perhaps it’s not a surprise that she gives no nod to the thumb-nosing irreverence toward death you find in Laurence Sterne’s “The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman” (or, more recently, Monty Python). Some readers may also feel it odd that she omits such obvious candidates as Virginia Woolf and — ahem — Shakespeare from this discussion.

But a full study of how authors address death in their work would run to multiple volumes, and the format of Graywolf’s “The Art of” series puts firm constraints of length on its authors.

Danticat does make many essayistic observations that serve the book well — conclusions that she, looking inward, came to on her own. She notes the way we sometimes find ourselves “rehearsing” our future bereavements. She questions how one can “prepare to meet death elegantly.”

“We are all bodies,” she writes, “but the dying body starts decaying right before our eyes. And those narratives that tell us what it’s like to live, and die, inside those bodies are helpful to all of us, because no matter how old we are, our bodies never stop being mysterious to ourselves.”

For authors, the elusive nature of death never stops posing a challenge.

“Having been exposed to death does help when writing about it,” Danticat notes, “but how can we write plausibly from the point of view of the dying when we have not died ourselves, and have no one around to ask what it is like to die?”

Far from being morbid, this small book is a bracingly clear-eyed take on its subject.

Complete Article HERE!