— In interviews with people who were dying, we learned they wanted to mark their final days with meaningful experiences and leave their affairs in order. It’s time to reset logistics, last days and legacy.

He died fuller of faith than of fears,

Fuller of resolution than of pains,

Fuller of honour than of days.

Inscription, Westminster Abbey, 1631

Why do we so often die badly? How does it happen that so many of us arrive at the end of life unprepared for the journey? Somehow, we are stumped when it comes to creating a better model of dying. Our unique qualities as individuals are lost in the processes of medical institutions and funeral homes. For those facing our last days, we have a pretty good sense of what’s involved.

Twenty years ago, I started a nonprofit organization called Older Adults Technology Services (OATS) based in New York City that helps senior citizens build new models of aging while learning technology skills. We use design thinking methods to create new programs for social impact, using approaches like co-creation, prototyping and customer satisfaction metrics.

We met with people in their hospice beds, in their homes, and on one adventurous occasion, in the Fabergé room at the Metropolitan Museum.

Recently we turned our innovation lens toward what was happening with older people in end-of-life situations to see if we could design new programs to help them. Using a design thinking methodology, we met with people who were dying and asked questions like, “What is a good day like for you?” and “If you could change one thing about your end-of-life process, what would it be?”

We met with people in their hospice beds, in their homes, and on one adventurous occasion, in the Fabergé room at the Metropolitan Museum. Some had been told they had months left, while others were living with just a few weeks in their prognosis. We visited other hospices around the country and spoke with social workers, chaplains, elder law attorneys and service providers. We read books on death and dying by Caitlin Doughty, Atul Gawande and Richard Rohr. We had weekly review sessions and talked to experts on business planning and branding and customer experience design.

We Are Failing at Dying

Here is what we learned.

We are failing at dying. Instead of a time for growth, deep connection, reflection and deliverance, our ends of life are consumed by petty distractions and institutional imperatives. The dying people we interviewed had not given up on life; rather they were full of desire to mark their final days with meaningful experiences and leave their affairs in order.

Yet almost everyone expressed sadness and frustration that they lacked a path for the right kind of death, the kind of passing that would reflect well the kind of life they had lived and the essence of the person they had become.

People described an entrenched group of institutions, resistant to change and wielding enormous power, which have grown to dominate the last stage of life — hospitals, funeral homes, home care agencies, religious organizations. When asked what they wanted instead people asked for three kinds of help: logistics, last days and legacy.

We were expecting ruminations on the duration of the soul, and instead people were preoccupied with getting the sheets clean and arranging pet care.

The Burden of Unmet Tasks

“Do you know someone who can come clean out my attic?” asked one woman in her fifties, fighting cancer and concerned that her overworked and grieving husband was sinking under the weight of daily tasks such as lawn mowing and housework. It was a startling response, in a bedside interview, to the question, “what’s most important to you now?” We were expecting ruminations on the duration of the soul, and instead people were preoccupied with getting the sheets clean and arranging pet care.

Logistics, it turns out, are top of mind for people who are dying. One woman spoke of her satisfaction in having arranged her funeral details and even set aside a dress to wear in her coffin. In an echo of Maslow’s famous hierarchy of human needs, the quotidian tasks form the base of the pyramid, and it seems difficult for people to elevate their thinking while still burdened with a laundry list of unmet tasks.

Many people commented on the need for legal help with logistics; writing wills, advance directives, health care proxies and financial plans. For many people, procrastination on legal matters resulted in family conflicts, loss of control over health decisions and anxiety about financial losses.

Unfortunately, once people were already in hospice, it was sometimes too late to interview lawyers and schedule notaries for important documents. Critical decisions about health, finances and death planning were left to caretakers and service providers, leaving the dying individual with little control over final decisions.

Death Needs a Reset

Being able to choose the location, activities and company of one’s last days was a recurrent theme. Despite being just days from passing, people expressed interest in writing articles, visiting museums, doing last trips with family members and exploring culture. My organization was able to arrange a robot tour of the Whitney Museum for one woman, who drove a telepresence robot around the museum from her hospice bed in Connecticut. At the end of the day, she drove the robot to the window and silently watched the sun setting over the river.

One clear message emerged from the interviews: death needs a reset. The handoff from doctor to hospice nurse to priest to funeral director is no longer the only path.

Finally, hospice patients were predictably focused on their legacies. We spoke for hours with people about their thoughts on post-death rituals, the value of a personalized funeral and the services that might help them express their individuality after passing. There was a great deal of openness to modern, innovative funeral approaches— “living funerals,” celebratory parties after death and eco-friendly caskets and cremations.

One clear message emerged from the interviews: death needs a reset. The handoff from doctor to hospice nurse to priest to funeral director is no longer the only path. What’s at stake is no less than our self-determination as free individuals. Like any life transition, death is a chance to explore and express ourselves in our mature stage, when we have perhaps the most important things to say. Modern culture offers endless chances for tailoring this most personal of events to our unique needs, but our social discomfort talking about death blocks us from acting.

Time for Innovative Thinking

We need a new approach to this experience, with higher expectations and more focus on dying well, not just expiring.

We found some truly innovative models in our research: “death cafes” where people gathered to explore themes of mortality and end-of-life planning; alternative hospices such as the Zen Hospice in California and Regional Hospice in Connecticut; digital death planning apps and sites such as Everplans and Everest Funerals; community learning programs run by the Plaza Jewish Community Chapel; and a national dialogue and events series sponsored by the San Francisco-based nonprofit Reimagine. Unfortunately, these programs only serve a small percentage of those who want them.

Here is a vision for reshaping end-of-life services and systems in accordance with what people asked for in the interviews.

Logistics: We need insurance and financial products that recognize the need for intensive health and personal assistance during the end-of-life period and provide enhanced benefits for people who need them. Government might create tax-free plans for legal fees associated with end-of-life plans, and the service sector should increase programs to ensure that people over the age of 60 have a legal will, advance directive and other necessary basic documents.

Last days: Incubate and accelerate a new service sector focused on proper preparation and programming for end-of-life. As major life transitions go, dying is on a par with getting married or having children, so let’s build an industry of death services to rival wedding planners and baby showers. Bring on the social entrepreneurs!

Legacy: Encourage innovation at end of life. We spoke to several innovators who had to pursue legislative recourse to overturn outdated regulations that restricted new approaches in hospice and funeral care. New York City has over 10,000 nonprofit organizations but only one nonprofit funeral home. We need to open the sector to more innovation and reduce regulatory barriers to innovation.

Fear of death and decline holds a strong sway over our minds as we age, and it’s no wonder that we are reluctant to face it. But the longevity revolution means we are living longer and expecting more from each day of our lives, and technology is adding powerful tools for managing our last days and legacies. We need a new approach to this experience, with higher expectations and more focus on dying well, not just expiring.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

People may not fear death, but they dread the process of dying

Native Americans, I read recently, have a rather beautiful concept called “second death”. The first death is when breath finally leaves the body; the second is when someone says your name for the last time.

This is not entirely dissimilar from the notion at secular Australian funerals of “celebrating” a life. Stories, humour, sorrow and love honour the lamented lost, and help cement them in our memories – they too live on, in a sense, while they are remembered.

What surprises me is how often non-believers make remarks like “she’s in a better place now” or “he’ll be looking down from above” – a paradoxical cultural legacy from the Christian belief in heaven.

Yet perhaps it is not really surprising. After all, belief in an afterlife is near universal across cultures from the earliest times, as evidenced by prehistoric grave sites – it’s utterly fundamental, which is a form of evidence.

Non-believers tend to reject the idea of an afterlife as mere wish fulfilment, but their rejection could equally be understood the same way, for example, as a reluctance to admit the possibility of judgment. (This is the thought of the Christian version of the “second death”, described in the New Testament book of Revelation.)

The atheist understanding, like the Christian’s, is entirely a matter of faith – no categorical evidence exists either way, though Christians can point to the biblical accounts of the post-resurrection appearances of Jesus.

Melbourne oncologist and writer Ranjana Srivastava, in her compassionate and thoughtful book A Better Death, notes how unprepared so many people are to die who have never thought about mortality and cannot accept it – even people in their 90s.

Having supported so many people of various ages and circumstances as cancer takes their life, she writes that many suffer a sort of existential pain – denial, absence of meaning, recrimination, regret – that can be as hard to bear as the physical aspects.

The urgent thing, she says, is to reflect before we age. “Dying well is about treating ourselves and others in the last act of life with grace and goodwill,” and there can be many moments of happiness, fulfilment and discovery that give meaning to life.

Death is today’s great taboo. People may not fear death, but they dread the process of dying. As Woody Allen quipped, he’s not afraid of dying, he just doesn’t want to be there when it happens.

These days, it seems, we all want to die painlessly in our sleep, preferably unexpectedly with no suffering beforehand. This is a stark contrast to previous centuries, when people wanted time to settle their affairs, take their leave of loved ones and, in particular, prepare to meet their maker.

Perhaps that’s a better death, both for the dying and for those they leave behind.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Hospice Nurse Hadley Vlahos Has Seen Incredible Things from People Facing Death That Defy Medical Explanation.

— Here’s What It’s Taught Her About Life

By Stacey Lindsay

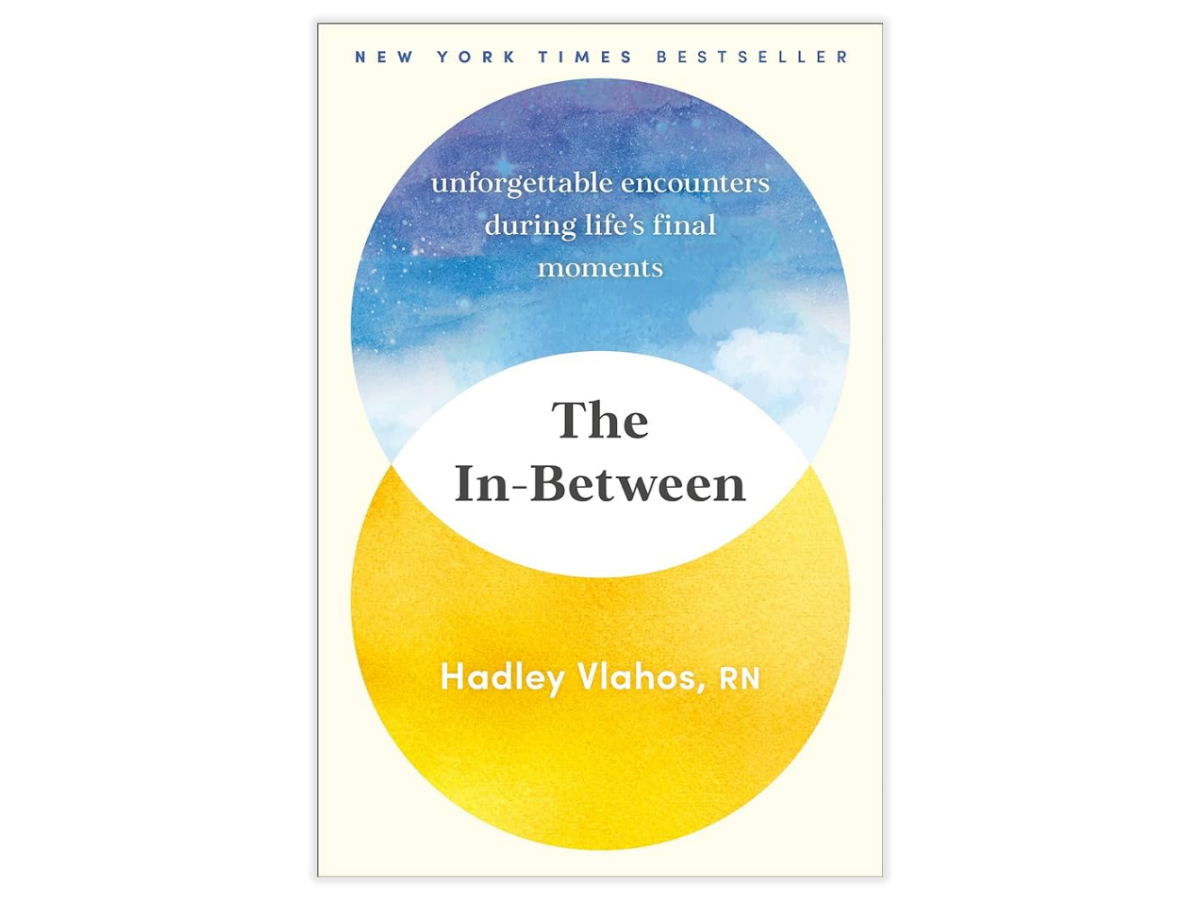

In her bestselling book The In-Between: Unforgettable Encounters during Life’s Final Moments, hospice nurse Hadley Vlahos writes the truth she sees in her job working with dying patients. “The one thing I can tell you for certain is that there are things that defy medical explanation and that in between here and whatever comes next, there is something powerful and peaceful.”

Alas, Vlahos still knows that “in between” and death are tricky topics. Death anxiety is real, she tells The Sunday Paper. But it is this angst that she hopes to dispel, both with her honest posts on social media (Vlahos has over 2 million followers on TikTok and Instagram combined) and in her book, in which she writes about all she’s witnessed and gained. As she says in a video post, “I found life again from caring for dying patients.”

Books on what those who are dying can teach us abound, and they share beautiful similarities in how we must grab the time we have and learn to embrace the beauty of passing on. Yet The In-Between is a book only Vlahos could write. In her captivating narrative, she layers between her accounts of people going to the other side, her own journey of facing poverty as a single mom, taking a chance in becoming a hospice nurse, and finding a Technicolor purpose—perhaps even more remarkable than she ever could have imagined.

I’ve been a hospice nurse for seven years now. And in the beginning, it was very hush, hush. You don’t talk about it. And I’ve noticed a huge cultural shift over the last two to three years since COVID, where people want to know. People realized how in the dark they were about what was going on, and they became hungry for knowledge. And it’s wonderful. Whenever you’re educated about something, it reduces the fear around it. I think everyone has that little bit of death anxiety, of course. Whenever we open up and talk about it, it makes it better.

You share these bone-chillingly incredible stories about things that happen to people as they are dying in hospice that, as you say, “defy medical explanation.” Many people connected with loved ones; in one story, Miss Glenda started talking to her deceased sister in the time leading up to her death. Tell us more about what you see.

We don’t learn in nursing school about people seeing deceased loved ones. So, whenever it first started happening, I thought it was a hallucination. Because that’s what I learned: People take medications, and then they hallucinate. And then I started talking to all my hospice coworkers and physicians, and I realized that they don’t believe that it is hallucinations. My first thought was maybe they’re all religious. But then I started being the one in control of my patients’ medication; I was the one who knew what they were taking and not taking. I would see the correlation between no change in medications, some patients not taking medications at all, and people with completely different religious backgrounds and diagnoses, and they were all having the exact same experience of their deceased loved ones coming to get them at the end. I started looking into it, wondering why this was happening and we don’t know why. There is no explanation as to why this happens and it is incredibly interesting to me.

There are a few different ones that happen. There is the seeing of deceased loved ones. There is also something called terminal lucidity, which is where people with dementia and Alzheimer’s will suddenly gain their memories at the end and be able to have conversations. I don’t witness it too much, but it is unbelievable to witness, and we don’t know why that happens either. The other one is what we call a surge of energy. That is where people at the end who have maybe been bed-bound for a while or have not been eating or talking much will suddenly be like, ‘I want to go into the living room and eat my ice cream and chat with my family.’ We don’t know why it happens, but it can sometimes give people a false sense of hope. And that is hard because loved ones will call me and say, ‘They’re doing so much better. I don’t even know if they need to be on hospice,’ when in reality, it usually means that they’re going to die very soon.

Going back to what we were talking about, whenever we educate people, they then know, oh, this could mean that my time is limited, and I need to enjoy this moment and take advantage of it.

This all sheds light on how we may force things on our loved ones who are dying, perhaps food or water, for instance, when they no longer need it. It is well-intentioned, but it speaks to a need for more understanding. What do you wish people who have a loved one who is dying knew?

I wish people knew that patients know that they’re dying. A lot of times, I watch this dance where someone is on hospice, or they’ve had terminal cancer for years, and no one wants to talk about it. Everyone wants to pretend that it’s not happening. What they think they’re doing is they are being kind by not saying, ‘I know you’re going to die one day,’ and not bringing up a difficult topic of conversation. But in reality, what I see with a lot of patients who confide in me is that they feel alone. They have all of these big feelings and thoughts and feel like they can’t talk to anyone about it because people change the subject. So I always tell family members, if your loved one brings it up, please talk to them and don’t try to change the subject. I know it’s uncomfortable. I know that the family members are trying to do the best thing, and they think they’re doing the right thing, but sometimes it leaves patients feeling alone.

You worked as a nurse in a traditional hospital setting before transitioning to hospice. How you speak of the hospice community paints a picture that it’s holistic and more harmonious. What things from the hospice world do you wish could be imbued in the medical world?

I have been what is called a case manager. If you’re in hospice, you have a registered nurse case manager. That means that I had patients assigned to me that were my responsibility. So, if a physician wanted something, the doctor had to come through me. If the chaplain wanted something, he had to come through me. If anyone wanted anything, they would have to come through me. I know not only what medications my patients take but also what prayers they’re saying with the chaplain and what conversations they’re having with the social workers. That kept things very cohesive.

A lot of patients tell me, and I’ve seen this from my own experiences, that it can feel like your cardiologist is telling you to do one thing and another doctor is telling you to do the opposite. No one in there’s saying ‘Okay, the cardiologist said this, let me call them.” Because so often, patients don’t know how to have the medical conversations that need to be had. There needs to be that one person. Right now, the only case managers we have in the hospital-type setting work for insurance companies, and that can be a gray area, as they’re usually on the phone and not caring for the patient and laying hands on the patient. So, I think other areas of medicine could learn from that approach, making it holistic.

You’ve said many times how positive of an experience death has been for so many of your patients. What can that teach us about life?

It can really teach us how to live a good life. Truly. I think that whenever we recognize that our life is short, and that’s such a cliche statement, but whenever we realize that, Okay, one day, I’m going to be on my deathbed. I see my patients, and I think, ‘That’s going to be me one day.’ So am I doing what I want to do every day so that when I’m in this position one day, I don’t have regrets? Or I can look back and do my life review with my own nurse and be like, ‘Yeah, I really went for it. Maybe I failed a little bit, but I really went for it. I really lived life.’ I think that that’s a really beautiful thing to be able to do.

When it comes to life wisdom, regrets, and looking back, what are some things you’ve heard from people as they pass on?

They tell me a lot! ‘Eat the cake,’ which I put in my book, is one of my favorites. I think about it all the time. But one thing that people have told me a lot, which I surmised from all of them, is that they lived for other people instead of themselves. That can mean a bunch of different things. That could be buying a new car because the person on the street has a new car. That could be choosing a career because that’s what your parents or society expected of you. Those are the regrets I’ll hear: They wish they would have just lived for themselves instead of others. Whenever I first heard ‘Don’t try to keep up with the Joneses,’ as someone said to me, I first thought the best way to live is to have no possessions and live a very low-key lifestyle. But as I started talking to more people, I realized it was more about: If you buy this house, is it because you love the house and you love coming home to this house every day? Does it make you happy? Or if you’re really into cars, does that car bring you joy? So I’ve realized that ‘Keeping Up with the Joneses’ means buying stuff for other people, not yourself.

What is the “in-between”?

It has a few different meanings. The main one is that I feel I’m with patients in between this world and whatever comes next. We get that little window of patients between worlds, and they seem to go back and forth. It’s my favorite period of time. I love being part of it.

On a more personal life side, the in-between for me was getting comfortable in the uncomfortable and being able to say, ‘Maybe I don’t have the answers, or maybe my life isn’t exactly how I want it to be, but I’m still finding happiness in this in-between phase.

Your book has been wildly successful. What did you hope people would take away as you wrote it? And what has surprised you now that it’s in so many people’s hands and ears?

I hoped that people would have less death anxiety. Whenever we turn on the TV, we see this tragedy—all the time. There was just a study that came out about how 80 percent of what we’re shown is just traumatic deaths. And I’m aware that that is not the reality for the majority of people. So, I was hoping that people would understand that you’re likely going to die in a slower way. And I think that that helps with people’s death anxiety. That was always my goal.

I was very shocked just how much people loved it. And I was very shocked at how much people related to me on a personal level. I was nervous. I quite literally wrote whatever my thought was. I put myself back in that moment in time, and whatever my thought was, whatever I was thinking, I just wrote. It was extremely honest, and I was a little bit nervous about it. I have been shocked by the messages, handwritten letters, and people just saying, ‘Thank you. I’m really glad to see someone else go through these things.’

And then how many ‘Eat the Cake’ tattoos! I think I’m up to 17 tattoos that I’ve seen. I love them so much!

Hadley Vlahos is a registered nurse specializing in hospice and pallative care. She is known as “Nurse Hadley” to her over two million followers online. Her first book, The In-Between: Unforgettable Encounters During Life’s Final Moments, is a New York Times bestseller. Learn more at nursehadley.com.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Does Someone Know When They’re About To Die?

By Jennifer Anandanayagam

Death is an uncomfortable topic for most of us but it is also one of the few universal experiences everyone will have. Scientists and doctors have long been investigating what happens to someone as they slowly slip away from this world, and while we don’t have all the answers, there are a few physical and behavioral changes you might be able to observe in someone who’s dying.

The person’s level of activity and movements might decrease significantly, noted the Hospice Foundation of America. They might spend most of their time sleeping. You might also observe that they’ve detached from what’s going on around them — interests, conversations, etc. They may also experience a loss of appetite and mental confusion. Physically speaking, someone who’s dying will experience a slowing down of their breathing and a drop in their blood pressure, per Everyday Health. “The fingers may get cold or turn blue. If you feel the pulse, it will be weak, then they start to develop an irregular type of breathing, and that’s a sign that things are pretty ominous,” added the medical director of the Hebrew Home at Riverdale in New York, Dr. Zachary Palace. A person in the last stages of life may also lose control of their bodily functions like urinating and defecating.

While these are the changes you’ll see in someone who’s close to death, what about them? Do they know they’re dying? According to certified hospice nurse Penny Smith, who goes by the name Hospice Nurse Penny on YouTube, they do, mainly because of what most people say before they die.

Dying people talk of having to ‘go away’

Penny Smith, who’spassionate about end-of-life advocacy and normalization of death, thinks that people who are close to death sometimes tell us that their time on earth has come to an end. “They might say, in no uncertain terms, ‘I’m dying soon,’ but often they tell us in metaphors,” she added.

They might say things like, “‘I need to pack my things,’ ‘I’m getting ready to leave,’ ‘I’m going on a trip,’ ‘I want to go home,’ or even just, ‘I’m tired,'” shared Smith. For the loved ones who are watching the process, it’s a matter of leaning into and listening to what they’re saying. By following their cues, you’ll really have the chance to say goodbye and express your feelings before they no longer understand, explained the hospice nurse.

People on their deathbeds are often concerned with mending relationships, navigating regrets, and spending time with loved ones. In fact, according to Fellow of the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine, palliative care physician, and author, Dr. Ira Byock, the words, “Please forgive me,” “I forgive you,” “Thank you,” and “I love you,” become even more meaningful when death is near. As a loved one who’s close to someone nearing their end, facilitating these important conversations could be the biggest gift you can give them.

Someone near death may feel peace

According to a 2014 study published in Resuscitation, people close to death sense being separated from their bodies and feel peaceful. The research involved interviewing 140 cardiac arrest survivors with near death experiences from the U.S., U.K., and Austria.

Neuroanatomist and author of the book, “My Stroke of Insight,” Dr. Jill Bolte Taylor, who experienced a sense of bliss when she had a stroke, per Forbes, thinks her euphoric sensations when close to death may have had to do with what part of your brain dies first. The left brain is often credited with all that’s logical, mathematical, and factual in our thinking, while the right brain is where creativity, imagination, and feelings thrive (via Healthline). Dr. Taylor thinks that when we’re close to death, it’s the right side of our brain that endures.

“When we’re on our deathbed, the left brain begins to dissipate. We shift out of all the accumulation and the external world because it’s no longer valuable. What is valuable is who we are as human beings and what we did with our lives to help others,” she told Forbes. Perhaps this is another explanation as to why someone who is about to die is concerned with mending relationships. Even if we don’t have all the answers about what people see and hear before they die, we do know that they want to spend their last moments in peace and love. Maybe this will help us do the best we can to make the experience of their passing meaningful for them.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Why Some People Wait To Die Until They’re Alone

By Jennifer Anandanayagam

Dying alone usually has a negative connotation attached to it. This is probably why movies portray it as sad and heartbreaking. On the flip side, dying while being surrounded by friends and family is often thought of as a good death. The person was loved and made to feel secure as they passed on. They didn’t have to endure the pain of dying alone.

But what happens in the final moments of death is a subject that’s largely still being discovered. No one really knows for sure definite answers to the big questions like “Does your consciousness continue after you stop breathing?” or “Will you have a better death if you have loved ones surrounding your bed?”

Social researcher and death studies scholar Glenys Caswell from Nottingham University noted that, for some people, dying alone is something that they choose of their own accord (via The Conversation). One of Caswell’s studies, which was published in the journal Mortality in 2017, involved interviewing 11 elderly persons who lived by themselves and seven hospice nurses about their thoughts surrounding dying alone. While there was some belief among the hospice nurses that dying alone is not something they’d endorse, Caswell found that for the older people, “dying alone was not seen as something that is automatically bad, and for some of the older people it was to be preferred.” They preferred it to having their freedom curtailed or being confined to a care home.

They might die alone to spare their loved ones pain

Lizzy Miles — a Columbus, Ohio-based hospice social worker and author of “Somewhere In Between: The Hokey Pokey, Chocolate Cake and The Shared Death Experience” — is of the opinion that some people can choose when they die. She wrote in the hospice and palliative medicine blog Pallimed that people who choose to wait and die alone might be doing so out of concern for their loved ones.

“We have those patients who die in the middle of the night. We hear stories about the loved one who just stepped out for five minutes and the patient died. We may have even witnessed a quick death ourselves. I believe this happens by the patient’s choice,” wrote Miles. She added that this happens mostly in instances when the dying person is a parent. “I believe it is a protective factor,” she explained.

Henry Fersko-Weiss, a licensed clinical social worker and executive director of the International End-of-Life Doula Association, feels slightly differently about the topic. While he doesn’t discount the fact that some people might die alone, he shared in a YouTube video that people like feeling connected and safe before they pass away. Fersko-Weiss said that “because of the way we think about death, [we] feel that we’ll be a burden to loved ones” if we let them see us die. Sparing loved ones the pain of it all might be at the heart of the decision but this is something friends and family should have an open conversation about, he added

Having an open dialogue with your loved one can help

No matter how painful those final moments might be, it can be a good idea to equip yourself with the right tools to have open conversations that foster understanding on both sides, say the experts. You might want to lean into what dying people want you to know about how they’d ideally want to go, and also assess your own emotions, cultural biases, and ideas around it. If you’re unable to broach the topic yourselves, enlist the help of hospice care workers or even a therapist.

It is possible that the person who is dying is concerned that the loved ones whom they are leaving behind will carry with them for the rest of their lives the burden of seeing them pass, shared Fersko-Weiss in the video. You could reassure them by saying something like, “Of course, we want to be there. It doesn’t matter how it looks or how it sounds or how emotionally difficult it may be to be present. It is part of our love for you that we would want to be there,” said the death doula.

How you choose to be present when someone you love is dying is a decision both the dying and those being left behind can arrive at together, per the experts. And, in the instance when your loved one chooses to wait and die alone, “openness created through discussion might also help to remove some of the guilt that family members feel when they miss the moment of their relative’s death,” added Caswell

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Can We Choose When We Die?

— What We Know

By Jennifer Anandanayagam

Movies, books, and even personal accounts record how, sometimes, people who are in the last stages of life hold on until something they dearly wished for gets resolved. It could look like reconciling with a loved one, spending time with someone they haven’t seen in years, or getting the blessing of a priest.

Given that there’s a lot we don’t know about what people see and hear before they die, is there any truth to the fact that we can choose when we die? Can we willfully resist death until we’re ready to let go? Science tells us that dying is a process: The person’s breathing slows down; their skin color and temperature change; they might experience difficulty breathing; they could sleep a lot more than usual; and their thinking and other senses may dwindle, per Health Direct. However, according to several hospice and palliative care workers, there is some truth to the thinking that people can hold on till they’re ready to let go.

Dr. Toby Campbell, a thoracic medical oncologist in the Division of Hematology, Medical Oncology and Palliative Care at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, told STAT News, “People in end-of-life care wouldn’t bat an eye if you asked if they think people can, to a certain degree, control those final moments. We’d all say, ‘Well, yeah. Sure.’ But it’s inexplicable.” Science might not have studied this phenomenon extensively nor arrived at one possible explanation, but there are some theories.

It could be related to a hormonal stimulus

What allows someone in the last stages of dying to prolong their life until some unfinished business is completed? Dr. Campbell thinks it could have something to do with a hormonal stimulus (via STAT News). People in the final stages of death “probably have some kind of hormonal stimulus that’s just a driver to keep them going. Then, when whatever event they were waiting for happens, the stimulus goes away, and there must be some kind of relaxing into it that then allows them to die.”

Charles F. von Gunten, a pioneer in the field of hospice and palliative medicine, agreed. “What people will do for one another in the name of love is extraordinary. I think of it as a gift when it happens,” he told The Washington Post.

However, there might be something else that happens that gives dying people a chance to enjoy what time they have left with loved ones before they die. Healthcare professionals call this “rallying” or “the surge,” as explained by licensed hospice nurse, Julie McFadden, who goes by the name Hospice Nurse Julie on YouTube. “A patient will look like they are actively dying or getting very close to death … And then suddenly, they perk up and they start acting like their old selves again. They may be hungry, eat, talk, laugh, joke around, be a little sassy with their family … They frequently do this and then pass away usually the next day.” Again, this isn’t understood well by healthcare workers but it does give loved ones a chance to say goodbye.

How to let go when death is near

Regardless of whether your loved one is holding on so they can spend more time with you or they are experiencing a surge in life just before dying, death is often something we aren’t prepared for. Some people may even experience what is known as “anticipatory grief” — feelings of loss even before their loved one has actually died.

What dying people want you to know, on the other hand, might change depending on their particular life situation; but there is a big possibility that there might be regrets, most of which might have to do with relationships.

The author of the book “Dying Well: Peace and Possibilities at the End of Life,” Dr. Ira Byock, seems to think that we can choose how we die. Byock, who’s a physician and advocate for palliative care, shared in his book that people who are about to die should take the time to say goodbye (via Help Guide). Sentiments like “I love you,” “I forgive you,” “Forgive me,” and “Thank you” are not overrated and should be prioritized between loved ones and the person who’s dying. For loved ones who are letting go, it might also be important to let your dying family member know that it’s alright for them to go and that you will be okay. It could offer immense relief to them when they need it most.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

End of life nurse shares what people see when they die

By Ella Scott

A hospice nurse in America has revealed her experience working in palliative care as well as detailing something many experience in their final months alive.

Los Angeles-based carer, Julie McFadden, took to TikTok last year to explain a common sign of death – ‘Visioning’.

According to End of Life Doula, visioning is when dying people believe they are talking to their deceased loved ones. They can also think that they have come to get them, or that they are in the room with them.

@hospicenursejulie What dead relatives before you die. It’s called visioning, and it’s a normal part of death and dying. #hospicenursejulie #hospice #learnontiktok #visioning #educational ♬ original sound – 💕 Hospice nurse Julie 💕

In a clip posted to social media in October 2022, Julie said: “Here is my most comforting fact about death and dying. The craziest things we see on hospice is that most people will start seeing dead relatives, dead loved ones, dead friends, dead pets before they die.”

Continuing on, the 40-year-old said that her patients don’t just start seeing their loved ones days before they die – it can happen up to a month before their death.

“We have no idea why this happens,” Julie elaborated. “We are not claiming that they really are seeing these people. We have no idea.

“But all I can tell you as a healthcare professional, who has worked in this line of work for a very long time, it happens all the time.”

Julie said that visioning happens so frequently that hospice workers regularly work to ‘educate the family and the patient’ on the topic before it commences. This is so that they are not ‘incredibly alarmed when it starts happening’.

She added: “And usually it’s a good indicator that the person is getting close to death, usually a month or a few weeks before they die. This brings me comfort, I hope it brings you comfort.”

Since posting the video last year, Julie’s sentiments have wracked up over 48,000 likes and 570,000 views.

The one-minute clip has also garnered over 1200 comments, with many finding solace in the carer’s admission.

One platform user wrote: “The last morning my mom was coherent she said she could already see my grandma, who died 42 (sic) years ago. In our culture we believe our dead loved ones come to lead you. We know her mom was there ready to welcome her to the other side.”

A second said: “Yep! My mother in law was telling her sister that their mother was packing a suitcase for her trip and picked out a dress for her to wear.”

“Yep I had a patient tell me his dog was on the end of the bed told me full description and name, told his wife made her smile,” said a third.

A medium headed to the comments section and wrote: “Spirit will tell us in a session they are the ones to grab our family at their time of death so they are not alone during the transition.”

Another social media user said: “My mother would often tell me that she just had a talk with my dad or one of her sisters. Started about a month before she passed and they looked good.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!