When Frank Schweigert dies, he doesn’t expect embalming, a burial vault or even a casket.

by Maria Wiering

[A]fter his funeral Mass, Schweigert, 67, wants to be placed directly in the ground, wrapped only in cloth, with little of the funeral trappings many people have come to expect.

And The Catholic Cemeteries plans to be ready to accommodate him.

The Mendota Heights-based organization, which oversees five Catholic cemeteries in the Twin Cities, is preparing to offer natural burial as an option as early as this fall. The trend, also called “green burial,” takes different variations, but aims to unite the body with the earth using little if any fossil fuel or non-biodegradable materials.

“It’s so much a part of our tradition,” said John Cherek, The Catholic Cemeteries director. “That’s the amazing part of it.”

The Catholic Cemeteries’ staff began exploring the option a few years ago, as they became aware of local Catholic interest in it. In many respects, the concept is as old as death itself, but the contemporary movement began in earnest about 20 years ago with the opening of the first green burial cemetery in the U.S. in South Carolina.

The California-based nonprofit Green Burial Council, established in 2005, certifies green burial practices for funeral homes and cemeteries. Its Minnesota listing includes only Mound Cemetery of Brooklyn Center as a “hybrid” green cemetery, meaning it offers both green and conventional burials, and Willwerscheid Funeral Home and Cremation Center in St. Paul as the only “green” certified funeral home. Other Minnesota cemeteries and funeral homes, however, do offer the natural burial options without formal certification.

Cherek said he isn’t certain that The Catholic Cemeteries will pursue certification, but preparations are underway in a section of Resurrection in Mendota Heights to make about 50 natural burial plots available this year, with the potential to add more in future years.

Burying the body

Natural burial begins with the preparation of the body, which is not embalmed. Because everything buried with the body needs to be biodegradable, the body is often not clothed, but rather wrapped in a shroud. In some instances, the grave is dug by hand, to avoid fuel-dependent machinery, and the body is transported to the gravesite by non-motorized means. The body may be encased in a biodegradable casket — options include those made from wood, bamboo and wicker — or simply shrouded before being lowered into the grave manually.

At Resurrection, the natural burial area is also being restored to native prairie. That means long grasses and wildflowers will eventually cover the graves. Instead of individual headstones, the plots will be identified collectively by monuments along paved paths.

As The Catholic Cemeteries’ leaders considered whether to offer natural burial, they surveyed focus groups and found more interest than anticipated. Several of those surveyed, such as Schweigert and his wife, Kathy, now feel passionate about the option.

“Since it’s our mission to bury the dead, and we offer full body and we offer cremation [burials] … this would be another option, and it may be attractive to folks who have thought they wanted cremation, but this might give them an alternative,” said Sister Fran Donnelly, director of LifeTransition Ministries at The Catholic Cemeteries.

In many respects, natural burial is a return to common burial practices before the rise of the funeral industry in the early 20th century. Although embalming dates to early Egypt, its contemporary use gained traction during the Civil War, when fallen soldiers’ bodies were transported home for burial.

Although there are common misconceptions that embalming or vaults are necessary for public health, that’s not the case, Cherek said.

Done properly, natural burial does not endanger the water supply or put bodies at risk of being dug up by animals, or spread disease, according to the GBC.

Funeral vaults — structures that surround the coffin in standard graves — are used as a way of stabilizing the ground around a grave for ease of grounds maintenance, preventing the otherwise inevitable sinking of topsoil, which displaces the coffin and bodily remains as they decay.

Embalming, meanwhile, puts chemicals into the ground, and vaults prolong or prevent natural decay, and many elements included in the burial — from suit coat buttons to casket hinges — aren’t biodegradable.

According to the Green Burial Council, American burials annually put into the ground 1.6 million tons of reinforced concrete, 20 million feet of wood, 17,000 tons of copper and bronze, and 64,500 tons of steel. Add to that 4.3 million gallons of embalming fluids, which contain toxins that could negatively impact the health of embalmers.

While some people think of cremation as a simpler option, it also requires chemicals, and toxins linger in the cremated remains.

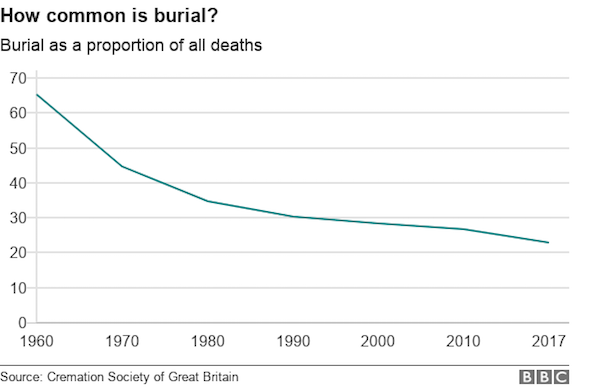

Cremation is permitted for Catholic burial, and its use is on the rise. However, the Church prefers burial of the body. The Catholic Cemeteries’ leaders think that natural burial might appeal to Catholics not only because of theologically-rooted ecological commitments, but also because it allows them to have a full body burial in a simpler form.

“Faith-wise, I think it says something about the resurrection of the body, that the body is intact, and it’s just going to return to the earth,” Sister Donnelly said.

Dust to dust

Schweigert, an administrator at Metropolitan State University in St. Paul, remembers reading decades ago about traditional Muslim burial, in which the body is placed directly in the ground. It struck him as a very natural way to approach death and honor the deceased, and over the years, the idea germinated in his mind as something he would prefer to the standard use of embalming, a casket and a burial vault. A parishioner of St. Frances Cabrini in Minneapolis, he contacted The Catholic Cemeteries a couple years ago to see if it was possible. He found out that “green burial” was becoming a trend, and that The Catholic Cemeteries was exploring the option. The organization later asked him to participate in a focus group on the topic.

The idea of placing the body directly into the ground with nothing to impede its return to the earth reminded Schweigert of something he observed as an altar boy: that the body and blood of Christ, if not consumed, were buried or drained directly into the ground.

“The earth was the most sacred place for the body of Christ, and the parallel between that and putting a loved one in the earth just seemed to me convincing spiritually,” he said.

And although Schweigert has strong feelings about not being cremated, which he sees as too industrialized and destructive of the body, he said his decision to choose a natural burial is also not a reaction to the funeral industry, which he respects, as he noted funeral directors have treated him and others well during times of grief.

He does, however, question the long-term sustainability of common methods, and he sees natural burial as a way to honor the environment, the dead and the Catholic faith.

Green or natural burial practices complement Catholic teaching about death, Sister Donnelly said, as well as the Church’s social teaching on caring for creation, which Pope Francis articulated in his 2015 encyclical “Laudato Si’: On Care for our Common Home.” Already, several Catholic cemeteries in the U.S. offer green burial options, and a 2011 survey by U.S. Catholic Magazine found that 80 percent of respondents would prefer a green burial.

Some religious communities are adopting natural burial as part of their commitment to caring for creation. Among them is Sister Donnelly’s community, the Sisters of Charity of the Blessed Virgin Mary, which has a cemetery at its motherhouse in Dubuque, Iowa.

In “A Reflection on Changes in Burial Practice” in The Catholic Cemeteries’ summer newsletter, retired priest of the archdiocese Father James Notebaart looks to Scripture and Church tradition and what they say about the sacredness of a burial place, recalling the words spoken in the Ash Wednesday liturgy: “Remember you are dust, and to dust you shall return.”

After noting that the natural burial process is the way most people — including Catholics and their Jewish ancestors — were buried for thousands of years, he wrote, “So the core of natural burial is to acknowledge our innate closeness to the earth as a creature of God’s own making. It acknowledges that the earth itself is holy because it is an icon of the One who created it.

“Today we have begun to step back to much earlier practices, those of the preindustrial world in which there was a more organic sense of how all things are related, both the natural resources and the human use of them. This awareness is shaping a new articulation of ecological ethics, of which Pope Francis is a leading proponent.”

Practical considerations

Choosing natural burial, however, does mean eschewing other common aspects of funeral and burial beyond the casket and vault.

According to state law, a person needs to be embalmed, buried or cremated within 72 hours of death, but refrigeration of the body allows burial to take place up to six days after death, said Dan Delmore, who owns Robbinsdale-based Gearty-Delmore Funeral Chapels and sits on The Catholic Cemeteries’ board. State law also requires embalming for a public open-casket wake, but an in-home or closed-casket wake is a possibility.

Delmore has been a funeral director for 42 years, and for the first 15 years of his work, no one questioned the practice of embalming; it was an assumed part of the funeral preparation, he said.

“There’s been a lot of change of heart in people, and it goes more along the lines of chemicals in general, not necessarily at the time of death, but wanting a life free of chemicals in general,” he said, comparing it to the organic food movement. A Catholic, he also sees natural burial as an appropriate accompaniment to the Church’s funeral rites, and he said he’s excited to see it embraced at Resurrection.

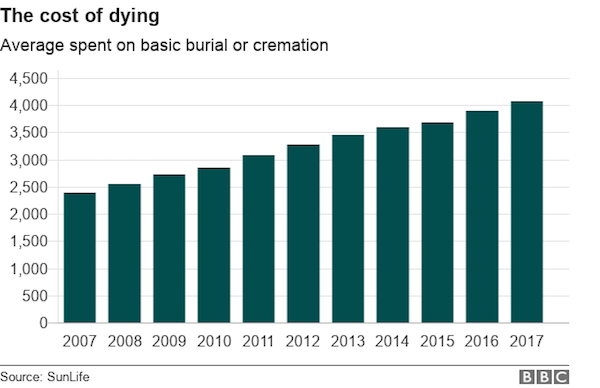

As it prepares to open its natural burial section, The Catholic Cemeteries is working on logistics, including cost, which is among the aspects that The Catholic Cemeteries’ focus groups said would affect their decision whether or not to have a natural burial. While 41 percent surveyed said they were likely to consider natural burial, complicating factors included already owning plots elsewhere; wanting to be buried next to a loved one who already has been buried in a conventional grave or wants to be; and wanting an individual headstone, which The Catholic Cemeteries’ current natural burial plan precludes.

Schweigert admits the idea of not having an individual headstone has taken some getting used to, but while that alone has dissuaded others, he’s not deterred. He recalled seeing a family burial plot in France that had a collective monument, and it’s reminded him that burials have been handled differently in different times by different cultures.

He puts it in perspective with the knowledge that after three generations have passed since a person’s death, his or her grave is not likely to be frequented by loved ones, and that there are other ways to leave a final mark on the world. For him, it’s more important to remove any barriers — physical and symbolic — between the body and the earth.

“This is a sacred moment for us,” he said of death and burial. “We want to have a way to do this with dignity, [and] we want a way to do this with our Catholic religion, so I’m very happy, too, that the Catholic Church has gotten involved in it.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!