The contents of my mom’s laptop were like a breadcrumb trail: her interests, her hopes and her plans for the future, even those that would never come true

By Kate Brannen

Not long after my mother died in 2014, less than eight months after being diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, my dad and I performed a ritual familiar to anyone who has lost someone they love: we went through her closet to decide what to hold on to. We kept her favorite pieces, like the cozy purple cardigan in which her scent still lingered, a few items of jewelry and her scarves.

A few months later, my father gave me her laptop. I needed a new computer and was grateful to have it. But its contents – photos from trips, a draft of her thesis from divinity school, Van Morrison albums in her iTunes – kept pulling me down rabbit holes. Whenever I sat down to do some work, I’d find myself lost in her files, searching for ways to feel close to her again.

Her computer activity was like a breadcrumb trail through her inner life: her interests, her hopes and her plans for the future, even those that would never come true.

The bookmarks in her Safari browser served as a compass on a journey into my mother’s mind. She used them like sticky notes, saving articles to return to, museum exhibitions to attend and beautiful hotels to visit. She bookmarked things like EssentialVermeer.com, a Wikipedia entry for Theological aesthetics, How to Dress Like a Parisian, and endless recommended reading lists.

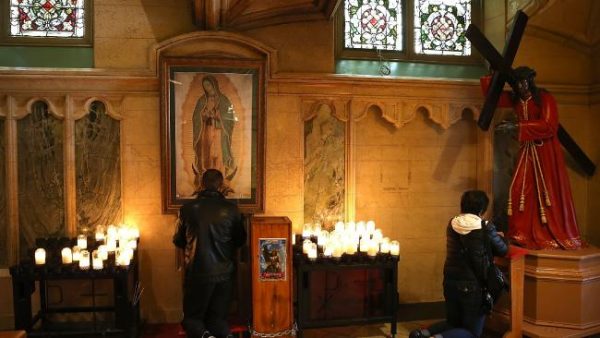

As I scrolled through them, I wondered about these clues: were they hints for how I should live my life? Suggestions for places I should go? Ideas to discover? The very first bookmark was “Resources for a Spiritual Journey.” Was that a little nudge from her? I explored each site methodically, not wanting to miss a word or a photograph, just in case I overlooked something from my mom: here’s what you need to know, here’s what I really loved, here’s how much I loved you.

Of course, not all bookmarks were treasure troves. Her health insurance company, for example, and some links no longer work. One took me to the old site of the Opera National de Paris. “You are looking for something?” the 404 error message read in broken English. “Yeah, my mom,” I think. “You seen her?”

Each bookmark corresponded to a time in her life. I pinpointed when she moved to London (places to stay in Cornwall and upcoming shows at the Tate) and when I got married (my wedding website). And there, toward the end of the list, a YouTube video of Kenneth Branagh delivering the St Crispin’s Day Speech from Henry V marked when cancer entered her life: my little brother sent it to the family when her chemo began, preparing us for the battle ahead.

A month later, she sent us Mel Gibson’s “Freedom” speech from Braveheart. I clicked on the bookmark and re-watched Gibson in his blue face paint, yelling: “They may take our lives, but they may never take our freedom!” That was my mom, the William Wallace of chemo: our fearless chief, bravely leading us into a gruesome battle.

But walking in mom’s online footsteps was also like crossing a field riddled with landmines. Without warning something would trigger my grief and my heart was ripped open again. The most painful were those that came just before the cancer battle speeches, before she knew she was sick. There, plain as day, were her plans and hopes for a future she thought stretched out before her.

“15 Ideas for a Children’s Discovery Garden,” read one bookmark from not long ago. This was my mom looking for ways to make her house magical for her grandchildren. At the time she had just one, my one-year-old daughter Maeve, and I could see that being a grandmother was going to be the defining role of the rest of her life.

Recently, I stumbled upon her bookmark of a CS Lewis quote: “We do not want merely to see beauty, though, God knows, even that is bounty enough. We want something else which can hardly be put into words – to be united with the beauty we see, to pass into it, to receive it into ourselves, to bathe in it, to become part of it.”

This is what my mom sought throughout her life, and was more successful than most at finding it. For me, the quote also evokes the day she died and how I’ve come to understand her death. She died on 15 December 2014, eight months after she was diagnosed.

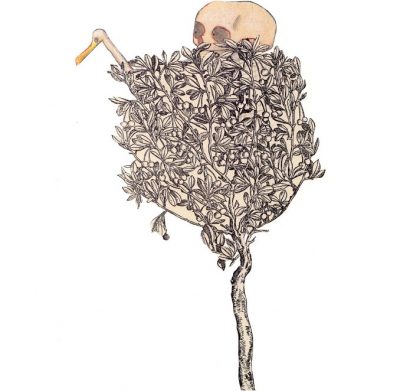

The days and weeks in late November and early December that preceded my mother’s death had been dark, overcast and cold. The grim scenery seemed to reflect the sorrow and fear that had overtaken my family. I kept taking photos at twilight of the dark silhouettes of tree branches set against the purple sky.

But the day my mom died was different. I came downstairs early that morning to relieve my older brother who had kept vigil by her bed all night. I sat alone with her as sunlight flooded in through the windows, filtering through the pink orchids that lined the windowsill.

As I sat there, I remembered what my mom had told me about the day I was born. The hospital had been busy that August morning but soon after she gave birth to me, my mom and I were left in a room alone. When she told the story, she always emphasized how wonderful it was to be on our own, just the two of us, how peacefully we slept. That’s how I started my life.

And that’s how the last day of my mom’s life began: just the two of us. I held her hand and watched her labored breathing. Looking at her, I thought about how I must have slept on her chest as a baby, taking in her warmth and feeling so safe in her arms.

That afternoon, my mother took her final breath. My two brothers and I left my father sobbing next to her hospital bed, which had been set up in the living room, and sat next to each other on a bench outside, watching the day’s final rays of sunlight bathe the front yard. After days and weeks of grim winter darkness, the scenery was radiant.

I couldn’t help but think my mom had become part of the beauty around us. The light seemed more intense, the beauty more vibrant because she was there in it. I was surprised that such a feeling of peace could be felt in the midst of that horrifying loss. I still cling to it and try to revive it in my memory.

My mom’s very last bookmark is for the Phillips House at Mass General Hospital, a place where she could get medical care and maybe spend her final days. The bookmark signifies to me that it was an idea she wanted to return to – an option to consider.

But her decline accelerated so fast. She died in hospice care at her home on Martha’s Vineyard.

The next bookmark is mine. I created it eight months after she died. It just says “Life Begins,” and it’s for the program for expectant mothers at New York Methodist Hospital in Brooklyn, where my son was born 14 months after my mom died.

When I first noticed these bookmarks back-to-back it took my breath away, like I’d stumbled on an essential clue to some mystery. Sitting right there was my mom’s disappearance from the world and then my son’s miraculous entry.

I’ve kept adding my own bookmarks to my mother’s list: 99 “essential” restaurants in Brooklyn, 25 weekend getaways from New York City, places where Maeve could maybe take dance lessons. Now my daydreams and thoughts for the future are piled onto my mom’s. From my mom’s happy life to its tragic ending to me trying to figure out how to be a person in the world without her, it’s all there.

Complete Article HERE!