With the coronavirus largely affecting people who are grandparent-aged, it’s a good time to talk with children about death.

My granddaughter was a few months past 3 years old when she first asked the question, as we sat on the floor playing with blocks.

“Bubbe, are you going to die?”

Nobody is as blunt as a toddler. “Yes, I am going to die one day,” I said, trying to remain matter-of-fact. “But probably not for a very long time, years and years.”

A pardonable exaggeration. Bubbe (Yiddish for grandmother) was 70, but to a kid for whom 20 minutes seemed an eternity, I most likely did have a lengthy life expectancy.

My granddaughter, Bartola (a family nickname, a nod to the former Mets pitcher Bartolo Colon), was beginning to talk about the deceased ladybug she found at preschool. Make-believe games sometimes now featured a death, though a reversible one: If an imagined giant gobbled up a fleeing stuffed panda, he would just spit it out again.

So I wasn’t shocked by what a psychologist would call a developmentally appropriate question. I did mention our conversation to her parents, to be sure they agreed with the way I handled it.

Such questions resurfaced from time to time, even before something she knows as “the virus” closed her school and padlocked the local playground. Though her parents talk about hand-washing and masks in terms of keeping people safe, not preventing death, even preschoolers can pick up on the dread and disruption around them.

Long before the pandemic, it occurred to me that grandparents can play a role in shaping their beloveds’ understanding of death. The first death a child experiences may be a hamster’s, but the first human death is likely to be a grandparent’s.

With tens of thousands of young Americans now experiencing that loss — most coronavirus fatalities occur in people who are grandparent-aged — it makes sense to talk with them about a subject that’s both universal and, in our culture, largely avoided.

Parents will shoulder most of that responsibility, but “grandparents have lived a long time,” said Kia Ferrer, a certified grief counselor in Chicago and a doctoral fellow at the Erikson Institute in Chicago, a graduate school in child development. “They’ve been through historical periods. They’ve lost friends.” We’re well positioned to join this conversation.

But that requires setting aside our own discomfort with the topic when talking to children. “It’s symptomatic of our society that we get nervous about what we tell them and how we’ll react,” said Susan Bluck, a developmental psychologist at the University of Florida who teaches courses on death and dying.

“But if they’re asking questions, they want to know,” she added. If we shy away, thinking a 4-year-old can’t handle the subject, “the child is learning that it’s a bad thing to ask about.”

We want kids to understand three somewhat abstract concepts, Dr. Bluck explained: that death is irreversible, that it renders living things nonfunctional, that it is universal.

We don’t need to prepare a lecture. “Only answer what they’re asking and then shut up,” advised Donna Schuurman, former executive director of The Dougy Center in Portland, Ore., which works with grieving children. “Listen for what they’re thinking. Let them digest it. The next response might be, ‘OK, let’s go play.’”

What and how much our beloveds understand depends on their ages and development, of course. Kids Bartola’s age will have trouble grasping ideas like finality.

They also tend to be awfully literal: My daughter, who knew better but spoke in the moment, once explained the Jewish custom of sitting shiva by saying that the family was going to keep their sad friend company because she had lost her father. “She lost him?” Bartola said wonderingly. “Did he blow away?” Oops, take two.

But 5- to 7-year-olds can think more abstractly. “That’s when they start understanding the cycle of life and the universality of death,” Ms. Ferrer said. And kids 8 to 12 “have an adultlike understanding,” she said, and may want to know about specifics like morgues and funeral rites.

What each age requires of us, experts say, is honesty. Euphemisms about grandpa taking a long trip, being asleep or going to a better place, create confusion. If someone died of illness, Ms. Schuurman advises naming it — “she got a sickness called kidney failure” — because kids get sick too, and we don’t want them thinking every ailment could be fatal.

Ms. Ferrer talks about a loved one’s body not working anymore, and medicine not being able to fix it. Even kindergartners know about toys that no longer work and can’t be repaired.

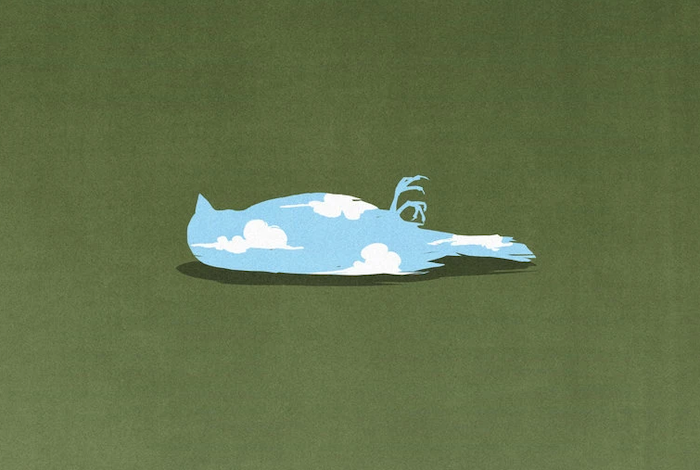

Nature can be helpful here. On walks, I’ve started pointing out to Bartola the flowers that bloom and then die, the leaves changing color and falling. A lifeless bird in the driveway presents an opportunity to talk about how it can’t sing or fly anymore.

Ms. Schuurman endorses small ceremonies for dead creatures. Wrap the bug or bird in a handkerchief or put it in a box; say a few words and bury it. “Let’s honor this little life,” she said. “It sets an example of reverence for life.”

Psychologists favor allowing children to attend the funerals of beloved humans, too, with proper preparation. In some families, religious beliefs will inform the way adults answer children’s questions.

The professionals I spoke with suggested some material to help grandparents with this delicate task. Ms. Ferrer is a fan of Mr. Rogers’s 1970 episode on the death of a goldfish and the 1983 “Sesame Street” episode in which Big Bird comes to understand that Mr. Hooper isn’t ever coming back.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!