What does it mean to create new life when one parent is dying?

Ben Boyer can still picture the expression on his wife’s face that night six years ago, as they talked over dinner at their favorite Italian restaurant in London. It had been four years since Xenia Trejo had been diagnosed, at the age of 33, with a malignant brain tumor that doctors said would eventually end her life. But as she sat across the table from Ben that evening, Xenia radiated joy. She felt strong, and after numerous rounds of treatment, her doctors had just told them that Xenia’s tumor was stable enough to do something she had long dreamed of: pursue a pregnancy. Now Xenia was asking Ben, What do you think? Should we try?

They had always planned to be parents, and the possibility had hovered even since Xenia’s diagnosis, but now it finally felt within reach. “Let’s do it,” Ben told her. By the time they left the restaurant and walked home together, they knew they would try to start a family. In that hopeful moment, the reality of their circumstances felt far away.

There are countless parents who don’t live to see their children grow up, but most of those tales involve unforeseen tragedy. The story of Ben and Xenia was different. When they learned of her illness, the future Xenia and Ben had long envisioned for themselves came undone, and an urgent reckoning followed. What would they fight to keep of the life they once imagined? In the face of a certain ending, they chose to create a beginning.

The number of people who confront this exact extraordinary convergence of birth and death is small enough that no one knows precisely how many are out there. “It is probably a very small number, though not an insignificant number,” says David Ryley, a fertility specialist at Boston IVF and a clinical instructor at Harvard Medical School. “I think you won’t find that data, because it hasn’t been collected.”

Yet there are outliers facing terminal illness who have forged ahead with plans to have children. Among them are a few who have risen to cultural prominence after sharing their stories: Paul Kalanithi, the neurosurgeon and author of the best-selling, posthumously published memoir “When Breath Becomes Air,” dedicated his book to his infant daughter, who was conceived after Kalanithi was diagnosed with metastatic lung cancer. Nora McInerny, host of the popular grief-focused podcast “Terrible, Thanks for Asking,” has widely shared her experience of having her son, Ralph, with her late husband, Aaron Purmort, who learned he had brain cancer before they were married. Ady Barkan — a prominent liberal activist who was diagnosed three years ago with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS, a neurodegenerative disease for which there is no cure — recently welcomed an infant daughter, his second child with his wife, Rachael King.

These are distinctly modern stories. For couples who confronted grim diagnoses before the turn of the millennium, the option to preserve their fertility was much harder to find and less likely to succeed. But the ability to freeze and test embryos improved dramatically in the early 2000s, bringing with it complex existential questions. What would it mean to have a baby in these circumstances for the parent who would die? For the parent who would live? For their child?

Xenia, Ben recalls, was not inclined to dwell on questions she felt she couldn’t answer. Her “entire M.O. was to live one day at a time, and she did not want to entertain larger metaphysical and moral debates about what this meant,” he says. He, however, was initially more hesitant. “I was a lot more nervous about what that meant for us, for her, and she was the one saying, ‘We should do it,’ ” Ben says. “For her it was, ‘I have to do this.’ I think she was put on this Earth to do it. She loved kids so much, it was not even a question. For me, I wanted to do whatever she wanted to do, but I also think I played the devil’s advocate more than once — ‘Here’s one possible reality, here’s another possible reality.’ But Xenia’s entire thing was, ‘If I let myself get mired in all the theoretical possibilities, I won’t be able to live a life at all.’ ”

And so they didn’t spend much time trying to decipher an unknowable future. Once the doctors said there was no reason to expect that a pregnancy would threaten her health, Ben says, “it was a given that we were going to try to do it.” In February 2014, Xenia gave birth to their daughter, Ella. Ben still recalls the euphoria of watching the nurse place their newborn on Xenia’s chest. He still can’t quite believe the song that played on the operating room radio, the refrain resounding in that moment: God only knows what I’d be without you.

Ben had first met Xenia in 2003, when they both worked for the BBC’s Los Angeles office. He was drawn immediately to her warmth, humor and adventurous spirit, and they fell in love quickly. Three years into their relationship, Ben transferred his job to London, and Xenia followed soon after. They were in their early 30s then, overjoyed to be living together for the first time in their tiny studio apartment. Ben remembers one particular afternoon in the winter of 2007, when they walked home together through falling snow, and he felt a deep sense of belonging: They would be married, have a family together, grow old together.

But in 2009, Xenia was struck with a wave of debilitating headaches. A seizure soon followed, which led to the discovery of the tumor in the frontal lobe of her brain. The doctor who delivered the news was shockingly blunt. “He immediately said, ‘So, you know, I assume you understand that you might die within a year,’ ” Ben recalls. “I remember thinking: This can’t be right.” As it turned out, it wasn’t: The couple quickly sought opinions from other doctors, who explained that while the prognosis was ultimately terminal, there was no reason to predict such a grim timeline.

They had been together for six years by then, and though they were not yet engaged to be married, their commitment to one another was absolute. Before Xenia started chemotherapy, the couple froze several embryos.

From the beginning, there were doctors who offered statistics, percentages, who told them how likely she was to still be alive in three years or five. There were also doctors who voiced a more universal truth: We can’t know with certainty what will happen, or when. Some patients with Xenia’s cancer died soon after diagnosis; others lived two decades or more. “Some people think of these things mathematically,” Ben says. “Some people think of them cosmically.” Xenia had always been, would always be, among the latter, he says. She would not be consumed by the inevitability of loss. “She refused to live like this was a death sentence,” he recalls, “even though it was explicitly a death sentence.”

Her treatments halted the progression of her illness, allowing them to resume their lives, and in 2011, they planned their wedding. Ben remembers the question Xenia once asked him, a few months before the ceremony: Are you sure you still want to do this?

He was. They were married that September on a historic ferryboat moored in San Diego Bay, surrounded by their loved ones. And two years later, over that dinner in London, they decided to move forward with building a family. They wound up not needing the embryos they’d frozen; Xenia became pregnant soon after they started trying to conceive.

From the moment Ella arrived, Xenia embraced motherhood, Ben says; she relished every minute of her 14-month maternity leave. She had always been a spontaneous and outgoing person, so it didn’t surprise Ben when she hopped on a train to Scotland with their baby to join Ben at a comedy festival, or showed up to bustling happy hours at their favorite pubs with Ella in tow. “We had an awareness that there was a finite number of experiences we were going to share together, and we knew we had to grab on to those moments,” Ben says. “We wanted to get out and experience whatever we could while we still could.”

Late in 2015, Xenia suddenly suffered an onslaught of seizures, and doctors confirmed that her cancer had begun to advance. Within months, the family moved back from the United Kingdom to San Diego, Xenia’s hometown. Her health continued to decline, and in the fall of 2017, Ben, Xenia and Ella moved in with Xenia’s parents, settling in the little house in San Ysidro where she had grown up. In those days, Xenia sometimes spoke to Ben of her sorrow for what she knew was coming. “She would say things like, ‘I’m so sorry you got stuck with this,’ ” he remembers. “She would ask if I regretted anything. And I would say, ‘Don’t be ridiculous.’ I would tell her, ‘This was the best thing of my whole life, that I met you, that I got to have this time with you.’ ”

Toward the end, a therapist suggested that Xenia might consider writing a letter to Ella, something she could read years after her mother was gone. Ben and Xenia were both aware of viral stories about dying parents who left behind written or recorded messages, birthday cards for their children to remember them by. But Xenia didn’t know who Ella would be at 16 or 20; she did not want her daughter to feel bound or burdened by parting words from a mother who had long been absent, Ben says. Xenia wanted Ella to be free.

Xenia’s decline was swift, her illness eroding her cognitive functioning, robbing her of language and distorting her personality. Through the darkest of those days, Ben says, Ella remained the one immovable tether to Xenia’s sense of self. Sometimes she would try to talk to her daughter, and couldn’t. “This,” Xenia would say to Ella, the only word she could summon; “this, this,” she would say with mounting urgency, and Ella would grow unsettled by the sudden intensity. But more often, there was an obvious contentment when the two were together. “Ella would walk in the room, and Xenia would immediately smile and become animated,” Ben says. “She was always so happy when Ella was around.”

On her last morning, Xenia awoke unable to speak. Ben and Ella lay with her as the house filled with family. She died that afternoon, a bright Sunday in May: Mother’s Day.

Buried in the digital archives of MetaFilter, an online message board that predated Reddit, is a question posed by an anonymous husband in 2010; he explained that his wife had been treated for an aggressive brain tumor, but they desperately wanted to be parents, and he wondered whether having a child was a wise or ethical choice. Hundreds of replies unspooled below his post, passionately voicing every imaginable viewpoint:

“You’re in for a world of trouble if you do it. But it may be the thing that you need to do.”

“Having lost a mother to cancer … I do think it is selfish to knowingly bring a child into the world knowing full well that the child will have to watch one of its parents die, and then grow up without them.”

“As someone whose father died when I was eight, I think you should do it.”

The medical community has grappled with this question as well. In 2005, the American Society for Reproductive Medicine convened a group of reproductive biologists, obstetrician-gynecologists, pediatricians and medical ethicists to weigh in on whether cancer survivors should be allowed the opportunity to reproduce, given the potential of a decreased life span. “It’s important to note there, the potential of a decreased life span,” says David Ryley, the Boston-based fertility doctor, who specializes in treating patients who have been given a cancer diagnosis. “Nothing in medicine is zero percent. Nothing in medicine is a hundred percent.”

The expert panel’s formal conclusion was clear, Ryley says, reciting it aloud: “The child in question will have a meaningful life even if he or she suffers the misfortune of the early death of one parent. While the impact of early loss of a parent on a child is substantial, many children experience stress and sorrow from economic, social and physical circumstances of their lives.”

“I could get hit by a bus today. How do I judge a couple who wants a child but may suffer misfortune?” Ryley continues. “Reproductive freedom is well established in this country, and this is a personal choice. We have patients seek counseling to help them get through that minefield, to not let them feel judged, to know that the choices they make are in the best interest of their life, their family, their relationship, and to understand that what is important is how they feel.”

Those sentiments are echoed by Merle Bombardieri, a therapist and author in Massachusetts who specializes in parenthood decision-making and often urges her clients to focus on inward reflection. For more than 30 years, she has counseled couples and individuals who struggle to decide whether to have a child, and she has worked with numerous people who faced grave health concerns.

This subset of her practice requires a somewhat different approach, she says, because they’ve already leaped beyond what she views as a foundational objective of her work, which is to ensure that her clients have considered their decision within the context of their own mortality. “Do you know that you will die one day?” Bombardieri says. “On one hand, that’s a ridiculous question, because everybody knows they’re going to die one day. But do you really know? Have you thought about what that means? Are you comfortable with your choice, knowing that you won’t be here forever? If you are, then you can feel more certain that it is the right choice.” For clients facing dire diagnoses, “this awareness has already come for them,” she says, which leaves other, more logistical factors to sort through: What is the prognosis? What sort of support system — community, family, friends — is available to offer help? What is the family’s financial situation?

Still, Bombardieri says, the most powerful motivations come from a more visceral place, where a person must reconcile hope with reality, and decide what they feel is still possible. “There are people who have always believed that they would have a child someday,” she says. “And, of course, there is the idea that — even if you die — you have left a child behind in the world. And that, too, is a kind of survival.”

Ella’s fingers grip her father’s, tugging him along as they walk a winding path through the San Diego Zoo, surrounded by life in all its strangest and most extraordinary forms: cheetahs and rhinos, gorillas and parrots. Ben and Ella are talking about how Xenia loved this zoo, and Ella, now 5, suddenly realizes that she isn’t sure what her mother’s favorite animal was. “I think I don’t know,” she says, her brow furrowed behind her violet-rimmed glasses, but she offers up her own favorite instead: “Flamingo!” she shouts.

They used to come here often as a family of three. These days, Ella usually visits with just her dad, or sometimes with friends she’s made at a therapy group for children who have lost a parent. On this idyllic October afternoon, the children’s area of the zoo is closed for renovation; when it reopens, it will include a brick engraved with Xenia’s name.

Ben took many photos of Xenia in this place, some of which are tucked into albums that Ella loves to look through. Later in the evening, after Ben and Ella return home from their outing, Ella sits cross-legged on the living room couch, studying an image of her mother outside the flamingo enclosure at the zoo. Xenia’s pose imitates the birds, one leg bent at the knee. “She has a pink shirt!” Ella says.

She pulls another album into her lap. “This is my favorite picture,” she says, pointing to a photo of herself at 5 months old, lying in bed beside her mother. Xenia is sleeping, a sheet drawn to her chin, but Ella is wide-awake, flashing a mischievous smile at the camera.

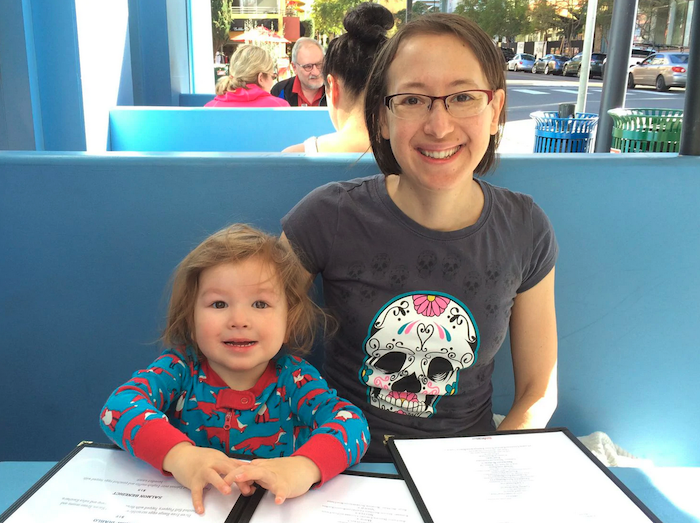

This particular album, capturing their first moments as a family, was Ben and Ella’s last gift to Xenia. Ella turns the pages past pictures of her birth, her ecstatic parents cradling their swaddled newborn. She resembles both her mother and father, but in photos with Xenia, the likeness is unmistakable: Ella has Xenia’s light brown hair and bespectacled dark eyes, the same wide grin and expressive eyebrows.

Their similarities run deeper, surfacing in new ways in the months since Ella started kindergarten at a Spanish immersion school, where she is learning to speak fluently in the native language of Xenia’s Mexican American family. The child’s exuberant sense of humor, her kindness, her boundless enthusiasm for Halloween, her deep sensitivity to music — to Ben, all of this feels like glimmers of Xenia.

Ella is growing up in the city where her mother was raised, where Ben now feels he has to stay. “Everyone is here,” he says. Everyone includes his parents — who own the condo he shares with Ella, and are his neighbors down the hall — and his sister’s family, and Xenia’s family, too. He can’t imagine taking his daughter away from here, even though it is a difficult place to find work in television production. When he and Xenia decided to have a child, their closeness to their families was at the forefront of their minds, he says. “We knew: This child will be surrounded by love.”

Outside Ben and Ella’s living room windows, the sun drops over San Diego Bay. When Ella reaches the end of the album, Ben scrolls through older photographs on his laptop. There is a portrait of Ben and Xenia’s wedding party, pictures of Ella trick-or-treating in a tiny bat costume, splashing in a backyard baby pool, sitting on her mother’s lap at Legoland.

Ben pauses on a photograph of Xenia framed by an array of vivid bouquets. “This was right after she was diagnosed,” he says. “Those are flowers that people sent.”

“What is ‘diagnosed’?” Ella asks.

“After we found out Mommy was sick, people sent flowers to say they were sorry about that,” Ben explains.

Ella nods and falls quiet. Then she smiles. “I wish I was a flower girl at your wedding,” she says.

There are questions that hover over the years ahead: What might Ella’s life be like when she is older — when she understands more about how she came into this world and what happened to her mother? How might she relate to Xenia’s memory? Every experience of grief is unique, its reverberations often impossible to predict. But the Kim family, who were patients of David Ryley 14 years ago, offers one glimpse of how a profound decision made in staggering circumstances can look more than a decade later.

Stacey Nichols met John Kim at a mutual friend’s party in Boston in spring 2003. He was an outgoing and deeply empathetic man with a “boundless wellspring of patience,” Stacey says — qualities that served him well as a school counselor who worked with kids with special needs. He moved in with Stacey three months after their first date; they got engaged that Thanksgiving.

Before their wedding in August 2004, John began suffering from sporadic gastrointestinal issues, and his doctor ordered diagnostic tests. The results were concerning, and further scans showed lesions on his liver. Three weeks after they were married, an oncologist told them that John had Stage 4 pancreatic cancer. “It felt like a complete emptying of my soul,” Stacey says of that moment. “All I could do was just be there, trying to make myself understand: ‘I’m here. I’m actually me. I’m not going to wake up from this.’ ”

Even as they were reeling, John wanted to know how his chemotherapy might affect their chances of having a child. The doctors didn’t have an answer. “There hadn’t been research on how this particular regimen affected fertility,” Stacey says. “The gist of what his oncologist said was, you know, patients who do these treatments for pancreatic cancer aren’t having kids; they die.” But John had always wanted to be a father, and they had to decide quickly whether they wanted to preserve that possibility. They postponed John’s treatment for one week so he could visit a sperm bank.

Eight months later, with John responding well to chemotherapy, the couple set out on a walk together and talked about starting their family. For the first time since their wedding day, Stacey felt a rush of pure joy and anticipation. “We didn’t know what was going to happen, but it felt almost defiant, somehow,” she says. “We felt like, this is a long-term plan. It is a decision only the two of us can make.”

They found out Stacey was pregnant with twins, a boy and a girl, in October 2005. When the babies were born the following June, John wrote their full names in the pages of a journal — Madeleine Ji Yun Kim and Riley Chen Woong Kim arrive!!! — alongside delicate drawings of fireworks. The exhilarating haze that followed lasted six months, Stacey says, before John’s cancer resumed its assault. The twins thrived as their father began to fade.

The exact chronology of John’s last days (what he ate, what time he took his medications — details Stacey could once recite with precision) are lost to her now. She remembers clearly, though, how she left the door to their bedroom open as John rested there in his final hours, so the sounds of his family living their day — the babies playing and giggling, splashing in their bath — could still reach him.

After John died in April 2007, Stacey made a point to speak of him often; she wanted her children to know that the subject of their father should never feel taboo. “They do love it if I bring him up; they love when I tell stories about him,” Stacey says. “I make sure to continue to remind them that it’s okay to grieve his loss for their whole lives, in whatever way they need to.”

Ten years ago, Stacey and her children moved to Portland, Ore., to be closer to her parents. Stacey is now 47, the director of marketing and communications at Lewis & Clark College, her alma mater; Maddie and Riley are 13, on the cusp of their high school years. Lately, Stacey says, they have started asking more questions about John, about what he was like, the similarities they share with him. As they’ve grown, they’ve become more aware of their biracial identity, their connection to John’s Korean heritage. They have lived all but 10 months of their lives without their father, and so their grief is not the loss of a known reality, but the absence of a possibility: Would John, who used to read Julia Child’s recipes aloud to Maddie, have celebrated his daughter’s love of cooking? What would it have been like for Riley to share his passion for video games with his dad, who was also an avid gamer? “I like to play chess, and I run cross country,” Riley says. “Those are things I think he would have been into.” He smiles. “You know, he was into nerd boy things, and I’m like that, too.”

Maddie thinks it must have been difficult for her dad to decide to become a parent, knowing he would miss out on so much of their lives. “But I’m so glad he did it. I think Mom would have been lonely. I mean, David is great,” she says, referring to Stacey’s boyfriend of several months, with whom the twins share an easy rapport. “But I still think she would have been lonely without us. And I feel like Dad’s entire side of the family would have missed him a lot more. They tell us all the time, ‘Oh, you really remind us of your dad, and that’s a really good thing.’ ”

The twins are especially close, often ending their days by taking walks together around the block to decompress and tell each other what’s on their minds. (“Some people say their brothers are annoying, but I really love my brother,” Maddie says.) Even without their father, Maddie says their family has always felt like enough. She wishes her dad could somehow know this. “I would like him to have that reassurance,” she says. “To be able to know that everything is okay, and that we are happy.”

John is the beginning of their story, and his family has since lived their way into a chapter he would not recognize, here in their lovely house on a tree-lined street in North Portland. His ashes rest on a shelf in the living room, a colorful gathering space strewn with books and musical instruments, often filled with the voices of visiting friends and family.

Even 12 years on, in this place he never knew, John’s absence sometimes echoes with startling immediacy: Stacey realizes with a jolt that she forgot to put on her wedding ring, and it takes a moment to remember that she hasn’t worn it in years; Maddie laughs, and her expression is suddenly her father’s; Riley holds Stacey’s hand and instinctively traces his fingertips across her cuticles, exactly the way John once did. They are here, and John is where John is, and there are moments when it still feels like the door between is open.

Ben has never forgotten something his mother once told him, soon before Xenia died: that for Ella, losing her mom would be the defining fact of her life. He thinks about this, in moments when he feels his aloneness most acutely — at play dates with other families, where he is often the only single dad, or when Ella asks for a French braid and he realizes he doesn’t know how to style her hair that way. “We just have to do the best we can for her,” he says.

When Ella decides to be a jellyfish for Halloween, Ben strings white lights from a clear umbrella and transforms his giddy kindergartner into a glowing sea creature. The two sing together, loudly and often, especially in the car. If there is somewhere Ella wants to go, something she wants to see, he takes her. This is Ben, but it is also Xenia, he says. Her way of being has become his.

And so, he feels, there is a sense of Xenia that is still palpable to Ella, even as her own recollections begin to fade. “Xenia would often say, ‘Will Ella remember me, or won’t she remember me? And which is better?’ ” Ben says. “And sometimes Ella will turn to me now and look worried, and she’ll say something like, ‘I think I don’t remember Mommy.’ ”

Ben does all he can to preserve the connection between Ella and her mother. On the first night that Ben and Ella lived alone together, the day they moved into their condo overlooking the bay, he tucked his daughter into bed in a new room and began a new ritual: Before Ella went to sleep, they talked for a little while about Xenia. At first, it was almost ceremonial; in the year that has since passed, it has become less of a nightly practice and more of an ongoing conversation, a constant referencing of things that Xenia once said or did or loved. Once or twice a week, Ella asks Ben to retrieve an old video camera loaded with dozens of hours of family footage, so they can watch it together.

Tonight, Ben is the one to suggest this, after Ella finishes her bath and changes into her pink nightgown. “Do you want to watch a couple of movies?” he asks, and Ella immediately shouts “Yes!” and dashes to her bedroom. Ben lies down on her twin bed and turns the video camera on, pointing the built-in projector toward the ceiling. “Hey, Ella, this is your first birthday party,” he says, and she grins and climbs in the bed beside him.

Ella will not remember her first birthday party. But someday she might remember watching the video of her first birthday party, and listening to her father tell her what the celebration was like. She might remember the way her mother looks in the film from that day, her slender frame draped in a striped top as she kneels and fills a large giraffe piñata with fistfuls of candy.

“Hi, Mommy,” Ella says, wiggling so her head rests on her father’s stomach. She watches as her family gathers around a picnic table where she and her parents sit before a cake, and Xenia gently rubs her baby’s back as everyone starts to sing “Happy Birthday.”

The scene unfolds, and the minutes tick past Ella’s bedtime. “Just one more, okay?” Ben says, and fast-forwards to a video taken when Ella was 3, at her first swimming lesson. When Xenia appears beside the pool, the progression of her illness is painfully evident — her hair unevenly shorn, her cheeks swollen from steroids.

“She looks very, very …” Ella trails off. She seems unsettled and climbs off the bed, crawling on the floor.

“Very what?” Ben asks her.

“Very, very …” but Ella can’t or won’t summon the next word.

In the film, Ben is talking to Xenia: “Impressive, right?” he says of their daughter’s enthusiasm in the pool, and Xenia nods and smiles.

In the bedroom, Ben is talking to Ella: “Mommy is gonna say something now,” he says. “Are you watching?”

“I’m watching,” Ella says as the camera closes in on Xenia’s face.

“We are very proud,” Xenia says, enunciating slowly.

They are together like this for a little while: Ella on the floor, gazing upward. Her father in the bed. Her mother in flickering beams of light. Then Ben says gently, “Okay, baby, it’s time for bed,” and turns off the projector. The past dissolves into shadows as Ella crawls back into the blankets, and the two of them lie there, side by side.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!