In 2016, the first year health-care providers were allowed to bill for an end-of-life consultation, nearly 575,000 Medicare beneficiaries took part in the conversations, new federal data obtained by Kaiser Health News show.

[T]he 90-year-old woman in the San Diego-area nursing home was quite clear, said Dr. Karl Steinberg. She didn’t want aggressive measures to prolong her life. If her heart stopped, she didn’t want CPR.

But when Steinberg, a palliative-care physician, relayed those wishes to the woman’s daughter, the younger woman would have none of it.

“She said, ‘I don’t agree with that. My mom is confused,’ ” Steinberg recalled. “I said, ‘Let’s talk about it.’ ”

Instead of arguing, Steinberg used an increasingly popular tool to resolve the impasse last month. He brought mother and daughter together for an advance care-planning session, an end-of-life consultation that’s now being paid for by Medicare.

In 2016, the first year health-care providers were allowed to bill for the service, nearly 575,000 Medicare beneficiaries took part in the conversations, new federal data obtained by Kaiser Health News shows.

Nearly 23,000 providers submitted about $93 million in charges, including more than $43 million covered by the federal program for seniors and the disabled.

Use was much higher than expected, nearly double the 300,000 people the American Medical Association projected would receive the service in the first year.

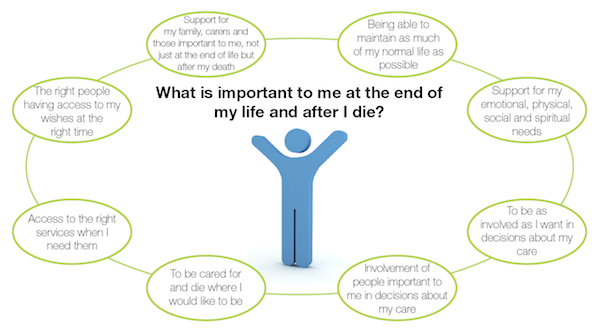

That’s good news to proponents of the sessions, which focus on understanding and documenting treatment preferences for people nearing the end of their lives. Patients, and often, their families, discuss with a doctor or other provider what kind of care they want if they’re unable to make decisions themselves.

“I think it’s great that half a million people talked with their doctors last year. That’s a good thing,” said Paul Malley, president of Aging with Dignity, a Florida nonprofit that promotes end-of-life discussions. “Physician practices are learning. My guess is that it will increase each year.”

Still, only a fraction of eligible Medicare providers — and patients — have used the benefit, which pays about $86 for the first 30-minute office visit and about $75 for additional sessions.

Nationwide, slightly more than 1 percent of more than 56 million Medicare beneficiaries who enrolled at the end of 2016 received advance-care planning talks, according to calculations by health-policy analysts at Duke University. But use varied widely among states, from 0.2 percent of Alaska Medicare recipients to 2.49 percent of those enrolled in the program in Hawaii.

“There’s tremendous variation by state. That’s the first thing that jumps out,” said Donald Taylor Jr., a Duke professor of public policy.

In part, that’s because many providers, especially primary-care doctors, aren’t aware that the Medicare reimbursement agreement, approved in 2015, has taken effect.

“Some physicians don’t know that this is a service,” said Barbie Hays, a Medicare coding and compliance strategist for the American Academy of Family Physicians. “They don’t know how to get paid for it. One of the struggles here is we’re trying to get this message out to our members.”

There also may be lingering controversy over the sessions, which were famously decried as “death panels” during the 2009 debate about the Affordable Care Act. Earlier this year, the issue resurfaced in Congress, where Rep. Steve King, R-Iowa, introduced the Protecting Life Until Natural Death Act, which would halt Medicare reimbursement for advance-care planning appointments.

King said the move was financially motivated and not in the interest of Americans “who were promised life-sustaining care in their older years.”

Proponents like Steinberg, however, contend that informed decisions, not cost savings, are the point of the new policy.

“It’s really important to say the reason for this isn’t to save money, although that may be a side benefit, but it’s really about person-centered care,” he said. “It’s about taking the time when people are ill, or even when they’re not ill, to talk about what their values are. To talk about what constitutes an acceptable versus an unacceptable quality of life.”

That’s just the discussion that the San Diego nursing-home resident was able to have with her daughter, Steinberg said. The 90-year-old was able to say why she didn’t want CPR or to be intubated if she became seriously ill.

“I believe it brought the two of them closer,” Steinberg said. “Even though the daughter didn’t necessarily hear what she wanted to hear. It was like, ‘You may not agree with your mom, but she’s your mom, and if she doesn’t want somebody beating her chest or ramming a tube down her throat; that’s her decision.’ ”

Complete Article HERE!