By Katy Butler

My parents lived good lives and thought they’d prepared for good deaths. They exercised daily, ate plenty of fruits and vegetables, and kept, in their well-organized files, boilerplate advance directives they’d signed at the urging of their elder lawyer. But after my father had a devastating stroke and descended into dementia, the documents offered my mother (his medical decision-maker) little guidance. Even though dementia is the nation’s most feared disease after cancer, the directive didn’t mention it. And even though millions of Americans have tiny internal life-sustaining devices like pacemakers, my mother was at sea when doctors asked her to authorize one for my father.

Our family had seen advance directives in black and white terms, as a means of avoiding a single bad decision that could lead to death in intensive care, “plugged into machines.” But given that most people nowadays decline slowly, a good end of life is rarely the result of one momentous choice. It’s more often the end point of a series of micro-decisions, navigated like the branching forks of a forest trail.

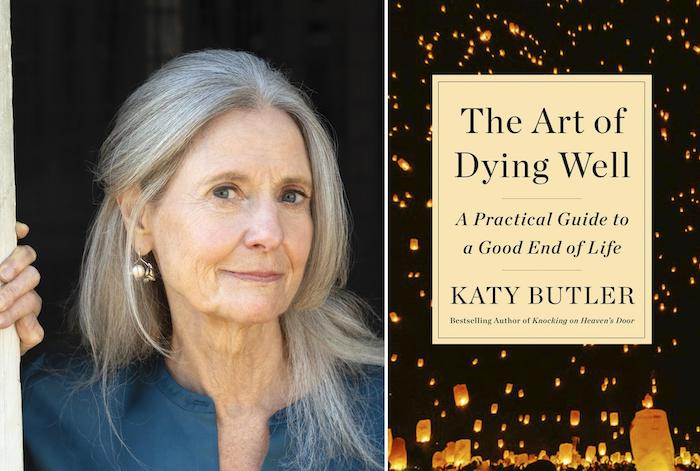

In our family, one of those micro-decisions was allowing the insertion of the pacemaker, which I believe unnecessarily extended the most tragic period of my father’s life, as he descended into dementia, near-blindness, and misery. In the process of researching my new book, The Art of Dying Well, I’ve met many other people who’ve agonized over similar micro-decisions, such as whether or not to allow treatment with antibiotics, or a feeding tube, or a trip to the emergency room, for a relative with dementia.

If there was one silver lining in my father’s difficult, medically-prolonged decline, it is this: It showed me the havoc dementia can wreak not only on the life of the afflicted person, but on family caregivers. And it encouraged me to think more explicitly about my values and the peculiar moral and medical challenges posed by dementia. At the moment, I’m a fully functioning moral human being, capable of empathy, eager to protect those I love from unnecessary burdens and misery. If I develop dementia —which is, after all, a terminal illness —I may lose that awareness and care only about myself.

With that in mind, I believe that “comfort care” is what I want if I develop dementia. I have written the following letter —couched in plain, common-sense language, rather than medicalese or legalese — as an amendment to my advance directive. I’ve sent it to everyone who may act as my guardian, caregiver or medical advocate when I can no longer make my own decisions. I want to free them from the burden of future guilt, and that is more important to me than whether or not my letter is legally binding on health care professionals. I looked at writing it as a sacred and moral act, not as a piece of medical or legal self-defense. I’ve included it in my new book, The Art of Dying Well: A Practical Guide to a Good End of Life. I invite you to adapt it to your wishes and hope it brings you the inspiration and peace it has brought to me.

Dear Medical Advocate;

If you’re reading this because I can’t make my own medical decisions due to dementia, please understand I don’t wish to prolong my living or dying, even if I seem relatively happy and content. As a human being who currently has the moral, legal, and intellectual capacity to make my own decisions, I want you to know that I care about the emotional, financial, and practical burdens that dementia and similar illnesses place on those who love me. Once I am demented, I may become oblivious to such concerns. So please let my wishes as stated below guide you. They are designed to give me “comfort care,” let nature take its course, and allow me a natural death.

- I wish to remove all barriers to a peaceful and timely death.

- Please ask my medical team to provide Comfort Care Only.

- Try to qualify me for hospice.

- I do not wish any attempt at resuscitation. Ask my doctor to sign a Do Not Resuscitate Order and order me a Do Not Resuscitate bracelet from Medic Alert Foundation.

- Ask my medical team to allow natural death. Do not authorize any medical procedure that might prolong or delay my death.

- Do not transport me to a hospital. I prefer to die in the place that has become my home.

- Do not intubate me or give me intravenous fluids. I do not want treatments that may prolong or increase my suffering.

- Do not treat my infections with antibiotics—give me painkillers instead.

- Ask my doctor to deactivate all medical devices, such as defibrillators, that may delay death and cause pain.

- Ask my doctor to deactivate any medical device that might delay death, even those, such as pacemakers, that may improve my comfort.

- If I’m eating, let me eat what I want, and don’t put me on “thickened liquids,” even if this increases my risk of pneumonia.

- Do not force or coax me to eat.

- Do not authorize a feeding tube for me, even on a trial basis. If one is inserted, please ask for its immediate removal.

- Ask to stop, and do not give permission to start, dialysis.

- Do not agree to any tests whose results would be meaningless, given my desire to avoid treatments that might be burdensome, agitating, painful, or prolonging of my life or death.

- Do not give me a flu or other vaccine that might delay my death, unless required to protect others.

- Do keep me out of physical pain, with opioids if necessary.

- Ask my doctor to fill out the medical orders known as POLST (Physician Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment) or MOLST (Medical Orders for Life Sustaining Treatment) to confirm the wishes I’ve expressed here.

- If I must be institutionalized, please do your best to find a place with an art workshop and access to nature, if I can still enjoy them.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!