“People’s deepest fears about death and dying often spring straight from a traumatic childhood incident or misshapen belief about the end of life that was passed on to them when they were kids.”

In previous postings I’ve talked about how postponing any thoughtful consideration of our death till it’s too late, can have disastrous consequences for us in terms of preparing for the inevitable. I addressed how our death-denying culture provides precious few opportunities for us to deal healthily with our mortality before it comes crashing in on us.

Why is dealing with death so hard for us? Early childhood messages about death sure don’t help. Think spooks, skeletons, things that go bump in the night, and specter of hell and damnation. From a young age, most of us have had it drilled into our heads that we shouldn’t ask questions or even talk about death because it’s either inappropriate, it’ll bring bad luck, or worse, hasten death.

How many times, as a child, did a relative, family friend, or even a beloved family pet simply disappear, never to be heard from or spoken of again? Or perhaps you were told that the absent loved one is now in heaven or asleep with the angels, the “D” word being avoided like Aunt Agnes’s infamous tuna surprise? Or maybe, when you were a kid, you were told that someone you knew had died, but that you wouldn’t be able to go to the funeral because that was no place for kids. And how much of the confusion, bewilderment, and unresolved grief from your childhood are you still carrying around with you today? Is it any wonder that, when faced with the prospect of our own death, we often feel like we’ve been ordered to belt out our swan song without ever having an opportunity to learn the tune.

In the first chapter of my book, The Amateur’s Guide To Death And Dying, I ask my readers to confront head-on the un-golden silence that surrounds the end of life. I invite them to consider the early messages they got about death and dying. I ask; how old were you when you first heard about or witnessed these things? What were the messages you picked up about death and dying from the movies or television? People often report that their deepest fears about death spring straight from a traumatic childhood incident or misshapen belief about the end of life that was passed on to them when they were kids. And, not surprisingly, most people report that they continue to carry these fears with them as adults.

I believe that’s criminal. I also believe that there is a better way to handle this delicate matter with young people than avoiding it, sidestepping it, or perpetuating a misconception. I believe we can break the vicious cycle of our culture’s death phobia by refusing to contaminate another generation with it. It would take a concerted effort, of course, and it would mean that we would have to resolve ourselves of our own fears first, but I believe it’s doable.

A good place to begin this effort is with the stories we read to and tell our children. Stories, both written and recited, become the basis of our children’s understanding of the world. Stories contribute to their language development as well as their critical thinking, and coping skills. Death and grief are particularly thorny subjects to communicate to children, not because our children are incapable of grasping the message, but because we, the adult storytellers, are often unprepared for, or uncomfortable with, the topics ourselves.

To address this problem, I developed a workshop titled: Exploring Death and Grief Through the Medium of the Children’s Story. In this workshop I help adults choose age specific messaging and images for their storytelling. I help them mold the basic concepts about death and bereavement into the arc of their story. And finally, I offer the workshop attendees tips on writing and illustrating their own story with the kids in their life.

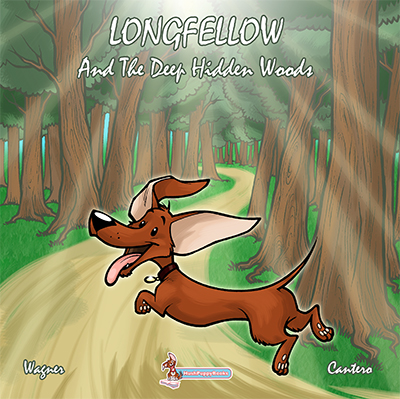

By way of example, I share with my audience my latest children’s story, Longfellow And The Deep Hidden Woods. This is the story of Longfellow, the bravest and noblest wiener dog in the world. As my story begins, Longfellow is a puppy learning how to be a good friend to his human companions, old Henry and Henry’s nurse Miss O’weeza Tuffy. By the end of the story, Longfellow has grown old himself, but he is still ready for one final adventure. What happens in between throws a tender light on the difficult truths of loss and longing as well as on our greatest hopes. Curiously enough, all the adults who have read my story say they think it’s actually a book for adults. Maybe so! I can be really subversive like that.

Writing and illustrating a children’s story with your kids can be an amazing bonding experience for both the adult and the child, but this is especially true when the topics are death and bereavement. It’s a project that will open the door to a life-long appreciation for and the affirmation of life, especially it’s final season. The discussion that will be part of your story-writing project will also help you reshape the coming generation’s perceptions about the end of life. It may also help you rethink the early message you received about death and dying when you were a kid.

Writing and illustrating a children’s story with your kids can be an amazing bonding experience for both the adult and the child, but this is especially true when the topics are death and bereavement. It’s a project that will open the door to a life-long appreciation for and the affirmation of life, especially it’s final season. The discussion that will be part of your story-writing project will also help you reshape the coming generation’s perceptions about the end of life. It may also help you rethink the early message you received about death and dying when you were a kid.

My workshop ends with one proviso. I caution the adults in my workshop not to wait until there’s a pressing need for the story writing or telling. I encourage them to start now, before grandpa or the beloved family pet is dead. I suggest that they get a jump on this project right away. Because, if they do, it won’t appear to their kids like they are trying to play catch up when death comes calling. I mean think about it; we don’t hold off teaching young people arithmetic till they get their first job making change at the grocery or the fast food counter, right?

Try to imagine how writing a story about death and grief with your kids or grand kids will change the trajectory of their life in terms of their understanding of this fundamental fact of life. Imagine if someone asks your kids or grand kids, twenty or forty years from now, what their earliest memories about death and dying are. Surely they will think back fondly on the time they spent with you as you helped them understand the marvelous cycle of life.

Will this one exercise inoculate your kids or grand kids from all the culturally induced fears, apprehensions and superstitions that abound in our death-phobic society? Probably not! But as the old adage goes, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.