Now they support medical aid in dying.

“It’s not just the pain, it’s the sense of isolation and aloneness and so on, which really can’t be assuaged by hospice.”

When Mark Peterson thinks about his mother, Rhea, he thinks of the petite woman who loved to play golf, and enjoyed sitting down with a good book.

But another thing that Peterson recalls about his mother is her courage at the time of her death.

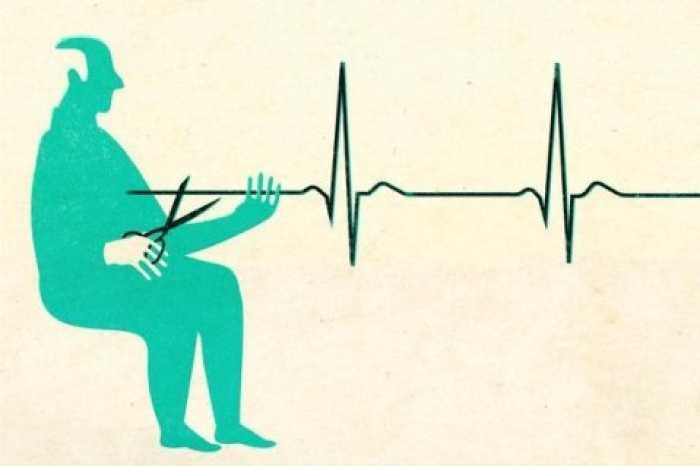

Because of the suffering and pain his mother endured, Peterson has become a vocal proponent for medical aid in dying, a way for terminally ill patients to choose to end their lives on their own terms.

State lawmakers are currently debating a bill that would legalize medical aid in dying in Massachusetts. The bill includes a variety of protections, including that the person must have a prognosis of six months or less to live, and go through a 15-day waiting period.

The initiative is already legal in a handful of states, including neighboring Vermont and Maine.

There are strong opinions both for and against the issue. Those in favor say laws in other states have worked the way they were intended. However, opponents are concerned that this will further burden the healthcare system, already taxed by the pandemic.

But behind the intellectual arguments for and against the issue are real people, like Peterson, who’ve faced the decline of a loved one and formed their opinion based on that sad reality. These are some of their stories.

A mother’s difficult choice

Rhea Peterson, who was born in 1907, began smoking cigarettes as a teenager – doctors at the time encouraged her to, she said.

Throughout her life, Rhea had been hardworking. She became a copywriter, and she won awards, her son said. She raised four boys. She also wrote books for adults and children.

Rhea also beat breast cancer — she underwent a double mastectomy in the 1940s.

But at the end of her life, Rhea was robbed of the activities she loved.

At 75, she was diagnosed with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or COPD.

Rhea quit smoking, her son said, “but COPD had its way with her, and basically she was no longer able to golf, and she got progressively weaker; she had to have what’s called an oxygen concentrator,” Peterson said. Using the concentrator meant she had to wear a nasal tube.

Rhea’s health continued to decline. Her vision started to go, and she began forgetting her medication. She also started becoming incontinent.

She didn’t want to go into a nursing home, Peterson said.

“She couldn’t play golf, she couldn’t read as much, she couldn’t get out and get around, and she realized she was losing some of her memory,” her son said.

“In 1985, she said, ‘I want to die,’ and the brothers all kind of freaked out,” Peterson said. “We had no idea what to do with that.”

No state had medical aid in dying at the time — Oregon eventually became the first, in the mid-1990s — and end-of-life care hadn’t yet progressed to what it is today. The options for Rhea were limited, and in early 1986, she declared she was stopping all treatments. She had decided she would try to live into that year because she was told it would be better in terms of taxes on the inheritance.

The five days between when Rhea stopped her medications to when she passed were anything but peaceful. She struggled to breathe. There weren’t any painkillers.

“It was excruciating and gruesome,” Peterson recalled. Rhea was 78 when she passed.

For the past 11 years, Peterson, a retired psychologist, has dedicated his life to researching and teaching people about end-of-life options. He has also testified before the Legislature’s Joint Committee on Public Health regarding the state’s proposed medical aid in dying bill.

When faced with end-of-life options, loved ones often panic, and sometimes get confused about what their family member would want, Peterson said.

“The decision-making can sometimes end up being distorted and cause great pain,” Peterson said. “Probably the biggest single example of that is when a child says, ‘I’ll do anything to save mom,’ and at times mom is subjected to very intrusive, aggressive efforts to save her life.”

End-of-life care and medical aid in dying

Thinking about today’s end-of-life care compared to what existed during the mid-1980s, Peterson agreed that it has improved, but sometimes palliative care needs to be about more than just treating pain.

“It’s not just the pain, it’s the sense of isolation and aloneness and so on, which really can’t be assuaged by hospice,” Peterson said. “People who get to the point where they’re sick of being sick and the indignities of not being able to wipe themselves, and endless pills, there’s so many ways that people get to the point and … they say, ‘I’m done.’”

Long before she passed away, Susan Lichwala’s mother made her promise that if she was ever in a state where she could no longer take care of herself and was being kept alive artificially, that Susan would request her mother be taken off life support.

Yet, in 2016, her mother, Lynne, was diagnosed with lung cancer — she had smoked throughout her life, Lichwala said. She started chemo, but with atrial fibrillation, or AFib, her heart wasn’t strong enough to tolerate it. She received radiation therapy, but it wasn’t enough to stop the cancer’s progress.

Toward the end of her life, Lichwala said she was clinging to being alive, but was no longer living. She died after a couple of weeks. Lynne’s care through hospice was excellent, Lichwala said, but being alive in that condition isn’t what she would’ve wanted.

“I know my mother would never have wanted to have been like that, yet there was nothing we could do about it,” Lichwala said, since the law didn’t allow for medical aid in dying. This despite the fact that, “There was absolutely no chance [that] my mother was going to live.”

Thoughts on the current bill before state lawmakers

Peterson noted that medical aid in dying shouldn’t be called suicide, saying that it’s a “very loaded negative term that’s used by people who oppose someone having the opportunity to end their life the way they would.” There’s also the stigma attached.

He does say, though, that the current bill covers things like preventing those who are depressed or suicidal from ending their lives.

Since both his parents have passed, Peterson said he’s dreamed about his dad, who died of a stroke when he wasn’t present; he wasn’t able to say anything to him before his passing.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!