[T]he headline on a recent Forward interview with Sheryl Sandberg asks if Sandberg can help Americans learn to grieve. Sandberg has certainly done all of us a great service by opening up a conversation about the way American do –- and don’t –- deal with death, dying and grief. In the essay that follows this headline, both Sandberg and Jane Eisner, who interviewed her, acknowledge that the rituals and structures of Jewish mourning can play an important role in processing our grief. As Jews, we are lucky. We do not need to create new ways of grieving; we need to look no further than our own traditions in order to learn how to grieve.

While the fact that everyone will die is universal, how we understand and respond to death is shaped by historical, cultural, political, economic, and, of course, religious, forces. Shared norms, values, and practices guide our expectations of how the bereaved should behave, of how we relate to the loss, of the responsibilities of the community, and of the social identities of the dead. As American Jews, therefore, the way we think about death is influenced both by our Jewish heritage and by the larger American culture.

In the United States today, death is primarily understood through the language and concepts of medicine, which focus on treatment, recovery and cure. Death is often perceived as a failure of the medical system, and talking about it makes many uncomfortable. Grief too is frequently seen as an individual and medical problem. Bereavement is a crisis to be resolved, and normal grieving behaviors are sometimes interpreted as symptoms of a psychiatric condition. For much of the 20th century, our understanding of grief built primarily on the psychoanalytic theories of Freud, and the work of grief was seen as letting go of the deceased, in order to free emotional energy for new relationships. Mourners were often told to “put the past behind”, “get back to normal”, and “move on”.

In the latter half of the 20th century, and into the 21st, new psychological models of grief emerged, primarily from researchers in North America and Western Europe whose methodologies allowed them to actively listen to the voices of the bereaved. My mother, Phyllis Rolfe Silverman, who died last June, was one of these scholars. In nearly 50 years of research in this field, she helped us to understand that bereavement is a time of change, a normal and expected life-cycle transition. Rather than something to recover from, mourning is a process of accommodation; it is not a linear process through a fixed set of stages, but a helix-like movement of negotiating a series of crises and accommodations. Mourning is an ongoing process of renegotiating a relationship, a “continuing bond”, with someone who is no longer physically present, and of reconstructing a meaningful world, and our place in it, following a loss. This is a process not of relinquishing an attachment or of giving up the past, but of changing our relationship to it. Grief is a life-long process, as the relationship to the deceased, and the meaning of the loss, is continually revisited and renegotiated as life events occur.

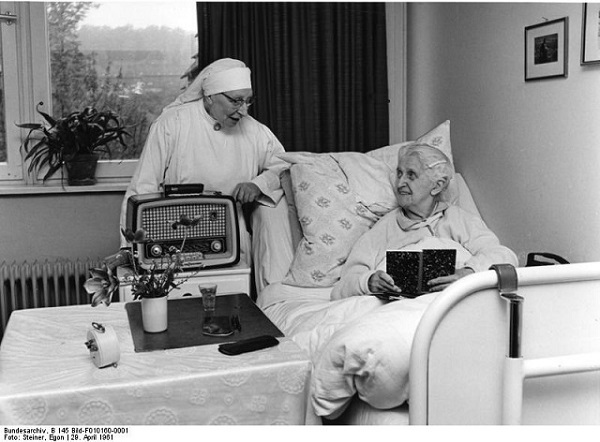

My mother always told us that Jews do grief well, that our Jewish traditions map perfectly onto the psychological experience of mourning. As I near the first anniversary of her death, and the end of my Jewish year of mourning, I understand now how right she was. Traditional Jewish laws prescribe a fixed set of mourning rituals and prohibitions, which are collectively referred to as Avelut (Hebrew for “mourning”) These rituals are designed to balance two core commandments: k’vod hamet –- honoring the deceased, and nichum avelim -– comforting the mourners. They make clear what is permitted and forbidden to the mourner during each phase of their grief, and outline for the community its responsibilities in caring for the dying, the dead, and the mourners. They recognize that what we need during the early days of intense pain and sadness is different than what comes later, as we accommodate to the empty space the death has left in our lives. Jewish rituals recognize that the individual is intertwined with the community, that, as the famous 1952 ethnography by Zborowski and Herzog declared, “life is with people”.

Our guidelines for mourning delineate who is considered a mourner (the parents, children, siblings, and spouse of the deceased), and the exact obligations and prohibitions guiding the behavior of each over time. These guidelines follow a clear progression, beginning at the moment of death, and continuing through the completion of the Avelut period, which is 30 days for a spouse, sibling or child, and one year for a parent. This is a highly structured process; as the mourners move from Aninut (entry into mourning) to Shiva (the first week), and then to Shloshim (the first thirty days) and eventually reach the end of Shanah (a year), they separate from, and then slowly return to, the social life of the community. Even after this year ends, those who have experienced a loss continue to participate in additional memorial rituals (yahrzeit, and, in the Ashkenazi tradition, yizkor) for the entirety of their lifetimes. At the heart of Jewish mourning rituals is recitation of the Mourner’s Kaddish. The kaddish, a prayer sanctifying God, is to be recited daily for the Avelut period, and must be said in the presence of a quorum of ten Jews.

Within a larger social context that still expects people to move on from their grieving fairly quickly, the year of Jewish mourning rituals, and the ongoing opportunities to remember the deceased, send the bereaved a strikingly different message. Our rituals recognize that ongoing mourning is accepted, expected and supported by communal norms, rather than being a reason to seek professional help. Jewish mourning rituals encourage the bereaved to temporarily withdraw from normal functioning, gradually accept the reality of the loss, mobilize social support, and find new meaning within the existing frameworks that guide their lives. In particular, the daily recitation of kaddish, and the annual marking of the yahrzeit, serve as a recognition that the memories of the dead will always be with us. These rituals acknowledge that death ends a life, but not a relationship.

By so publicly speaking of, and writing about, her grief, Sheryl Sandberg has powerfully reminded us that we need to acknowledge, make room for, and talk openly about grief. But it is not her job to teach us how to grieve. We have the wisdom of our Jewish traditions to do that.

Complete Article HERE!