— How science is reviving this ancient connection

By Nick Jikomes

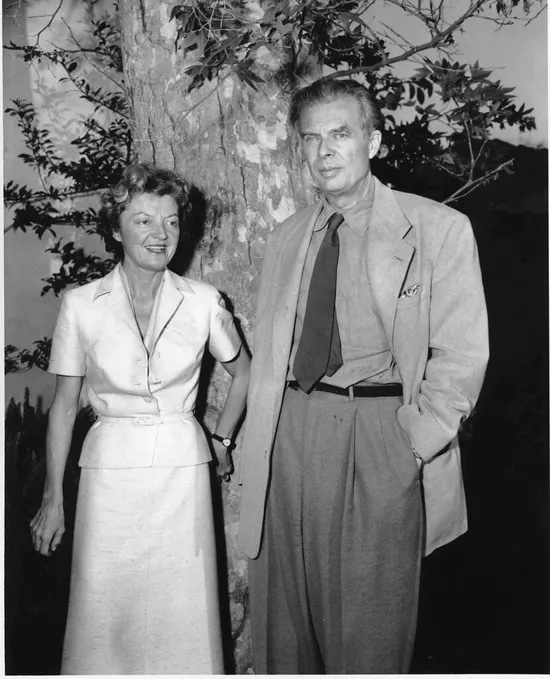

In November 1963, the writer and psychedelic explorer Aldous Huxley laid in bed, unable to speak. He was dying of cancer. One of his final acts was to pass a handwritten note to his wife Laura.

His famous last words: “LSD, 100 µg, intramuscular.”

It was Huxley’s dying wish: a large dose of acid, please. Laura Huxley fulfilled the request twice during her husband’s final hours.

First synthesized 25 years before Huxley’s death, LSD was still legal in 1963. Scientists were studying it as a potential treatment for alcoholism and other ailments, as well as investigating its similarity to other psychedelics. It wasn’t until 1968 that the federal government outlawed these drugs due to their association with the cultural turbulence of the 1960s.

Today, several decades later, terminal cancer patients are once again taking psychedelics. This time around the drugs are being administered by doctors and scientists in controlled settings—and they are not microdoses. The results of this research have been nothing short of remarkable.

Alleviating anxiety and despair

Terminal patients often suffer from feelings of intense anxiety and despair after receiving their diagnoses. For many, this is just too much to bear. The overall suicide risk for these patients is double or more compared to the general population, with suicide typically occurring in the first year after diagnosis.

Terminal patients have twice the suicide risk of the general public. Psychedelics may help reduce their fear and suffering.

That’s where psychedelic therapy may help. After a single large dose of psilocybin, taken in a curated space and supervised by a pair of doctors, many patients report feeling reborn. It’s not that the underlying physical disease has been cured. Rather, the drug prompts a shift in the theme of their emotional self-narrative—from anxiety and despair to acceptance and gratitude.

It may seem curious to think about psychedelic drugs, often associated with hippies and the Grateful Dead, as clinical-grade tools for overcoming our primordial aversion to death. But maybe it shouldn’t be. Maybe this is only surprising if your window of historical perspective is too narrow. Maybe these “novel findings” are, in a sense, a return to somewhere we’ve been before.

Psychedelics at the dawn of civilization

In late 2020 I spoke to Brian Muraresku, author of The Immortality Key: The Secret History of the Religion With No Name, about the use of psychoactive plant medicine throughout antiquity. Our podcast conversation covers this history in more detail, but it’s clear that humanity’s relationship with psychoactive plants extends back at least to ancient Greece—if not further. It’s hard to look at prehistoric cave paintings like the Tassili mushroom figure and not wonder if psychedelics played a part in their creation.

Western philosophy may have developed with help from psychedelics as well. In Plato’s well-known allegory of the cave, a group of prisoners live chained to a cave wall, seeing nothing but the shadows of objects projected onto it by fire. The shadows are their reality; they know nothing outside of it. Philosophers, Plato states, are like prisoners freed from the cave. They know the shadows are mere reflections, and they aim to understand deeper levels of reality.

Was Plato tripping?

If that sounds like someone who’s explored those deeper levels with psychedelic assistance…well, maybe it was. In his book, Brian Muraresku explores the significance of the Eleusinian Mysteries, secret ceremonies that involved death and rebirth. For centuries, philosophers and mystics traveled to the Greek town of Eleusis to partake in a ritual that involved an elixir known as pharmakon athanasias, “the drug of immortality.”

“Within the toolkit of the archaic techniques of ecstasy–plant medicine just being one among many–something you find again and again, in Ancient Greece and other traditional societies, is this sense that to ‘die’ in this lifetime, or achieve a sense of timelessness in the here and now, is the real trick.” -Brian Muraresku

Contemporary archaeologists, digging outside Eleusis, have unearthed ancient chalices containing a residue of beer and Ergotized grain. Ergot is a fungus that grows on grain. It produces alkaloids similar to LSD. It’s possible, then, that influential thinkers like Plato were inspired by genuine psychedelic experiences.

This connection between psychedelics and death didn’t end with Eleusis. It survived, often repressed and hidden from view, right through the time of Aldous Huxley.

The connection re-emerges in the 1960s

In the 1960s, Timothy Leary co-wrote a book called The Psychedelic Experience: A manual based on the Tibetan Book of the Dead. Leary, the exiled Harvard professor and psychedelic guru, dedicated the book, “with profound admiration and gratitude,” to Aldous Huxley. It opens with a passage from The Doors of Perception, Huxley’s essay on the psychedelic experience. Huxley is asked if he can fix his attention on what the Tibetan Book of the Dead calls the Clear Light. He answers yes, “but only if there were somebody there to tell me about the Clear Light.”

It couldn’t be done alone. That’s the point of the Tibetan ritual, he says: You need “somebody sitting there all the time telling you what’s what.”

Huxley was describing a trip sitter, someone who guides a person along their psychedelic journey. Sometimes it’s an ayauasquero in the heart of the Amazon. Sometimes it’s a doctor holding your hand in a hospital.

Seeking rebirth within the mind

In his book, Leary grounded Eastern spiritual concepts in the understanding of neurology we had at the time. The states of consciousness achieved by meditation masters and those induced by three hits of Orange Sunshine, he wrote, may actually be the same. Both involve dissolving the ego (“death”) and allowing it to recrystallize as the default mode of consciousness returns (“rebirth”).

Leary wasn’t talking about magic. Scientists know these as “non-ordinary brain states,” inducible by rigorous attentional practice (meditation), pharmacological intervention (psychedelics), and organic decay (dying).

The ability of psychedelics to induce these remarkable brain states may also be why they’re showing such promise in alleviating the very ordinary fear of death.

Today’s psychedelic treatments: Coping with death

So what, exactly, has recent research on psilocybin as an end-of-life anxiety treatment involved?

A few small studies have seen psilocybin administered to dozens of cancer patients. They’ve been conducted in a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled fashion. In general, a large majority of patients showed sustained, clinically significant reductions in measures of psychosocial stress and increased levels of overall well-being.

For example, in one study, 80% of the patients found that a single dose of psilocybin quickly relieved their distress. Remarkably, in some patients that positive effect lasted for more than six months.

Sprouting new physical connections

What’s going on at the neuronal level to produce those changes? We don’t know for sure, but some preclinical research has given us a hint. Both psilocybin and LSD have been shown to induce rapid and lasting antidepressant effects in lab animals.

Early studies hint at how psychedelics may produce positive changes in the brain.

Early indications are that psychedelics may allow brain circuits to rapidly sprout new physical connections. This is exciting, but again: These are non-human studies, and it’s early.

It’s gratifying to see any of these studies happening, frankly. This is research that’s been stalled by the Schedule I status of psychedelics for half a century. Much of this work requires obtaining a special federal waiver to study banned substances, which slows progress.

Potential help for end-of-life patients

Fortunately, the FDA recently designated psilocybin therapy as a “breakthrough therapy” and the DEA has proposed increasing the supply of psilocybin for research. This should speed up the rate at which we understand the clinical efficacy of psilocybin and related psychedelics.

Here’s more good news: In terms of psilocybin’s efficacy as a treatment for end-of-life anxiety, larger human trials are already underway.

Dr. Stephen Ross, one of the field’s leading researchers, has described the significance of this work: “If larger clinical trials prove successful, then we could ultimately have available a safe, effective, and inexpensive medication—dispensed under strict control—to alleviate the distress that increases suicide rates among cancer patients.”

Huxley: Ahead of his time

In one sense, Aldous Huxley was ahead of his time. More than a half-century before today’s renaissance in psychedelic research, his own experiences had evidently brought him to the conclusion that the best way to experience death was in a psychedelic trance.

In another sense, though, Huxley was one in a long line of creators stretching back to ancient Greek philosophers and perhaps even to prehistoric cave artists. They may all have used psychedelics to catalyze their outward creativity and comfort their inner distress.

Huxley titled his famous introspective essay, The Doors of Perception, after a quote from the English poet, William Blake: “If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to [us] as it is, infinite.”

We will never know what he experienced in the final hours before his death, after handing that note to his wife. I like to think that for him, the last breath seemed to last forever.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!