By Michael Joe Murphy

[O]wn a pet? Eighty-five million American households do — at least 43 million of them with dogs, an estimated 36 million with cats — beloved friends, companions, often considered family members. Photos of pets being rescued from Hurricane Harvey are a reminder of how much we treasure them. As we cherish them no less than our closest human companions, the loss of a pet often brings intense pain. For advice on coping with that grief, and the difficult decisions facing owners upon the loss of a pet, the Orlando Sentinel Editorial Board sought out Dr. Ron Del Moro, a licensed mental-health counselor with the University of Florida’s Veterinary Hospitals.

Q: What can a pet owner expect to feel over the loss of a pet?

A: I am not sure what one may expect, as there are an infinite range of emotions that losing a loved one can produce. The key for people experiencing loss is to allow oneself to feel whatever comes up without judging it. Many people I work with feel a deep loss when their pet dies. Extreme sadness, loneliness, and guilt are some of the most common emotions I see.

Q: What can a person do about those feelings?

A: One of the best things to do is not to judge our feelings (or the feelings of someone else going through it). We all deal with loss and grief differently; there really is no right or wrong. With that said, I feel that guilt and anger, though common, are misplaced and can be unhealthy. Often these emotions are masking deeper feelings of sadness.

The key is get support wherever we can. It is healthy to feel our emotions and be able to talk it through with people we trust (including a mental-health professional).

An individual’s way of grieving will differ from the way other people grieve. One’s grieving process also will differ in intensity and duration in the losses one experiences throughout your lifetime. Following are a few of the many ways that grief can be expressed and healing enhanced:

• Open expression of emotions such as crying, conversations about loss, etc.

• Drawing, writing poetry, or other artistic expressions

• Internal processing, thinking about the loss, trying to make sense of it, often done during activities such as meditation, exercising, bike riding.

• Dedicating time to animal organizations.

• Committing to make positive changes in your own life.

• Making scrap books or photograph albums of your pet.

• Keeping a written documentation of your feelings/journaling.

Again, there are infinite healthy ways to cope with loss and grief; it is very much a unique individual process.

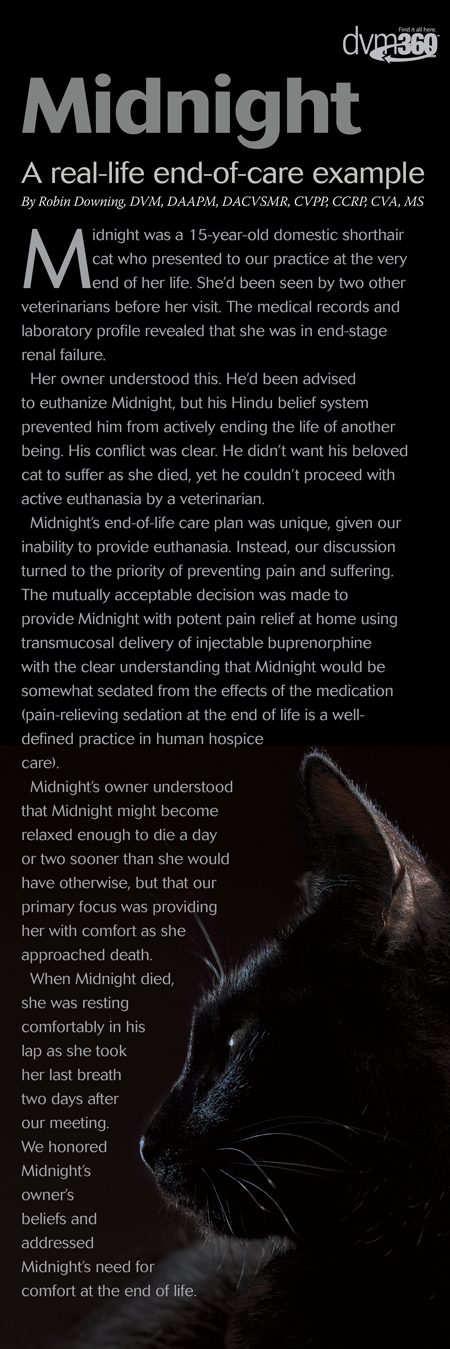

Q: When is the right time to euthanize a pet?

A: Again, I cannot make that call. Only a veterinarian and the owner can answer this question, hopefully together. I don’t know when the “right” time is, and I would like to think that euthanasia is an appropriate and humane step to take to end pain and suffering when there is a low likelihood that our loved one is going to feel better. I often think quality of life is a key factor in this very personal decision. It hurts to see animals suffer without hope of healing.

Q: Should an owner stay during euthanasia?

A: Again, this is an extremely personal decision; there is no right or wrong. I always tell people, try to avoid “shoulding” on yourself and others. I recommend that people to take time and think about this decision and discuss it with family and/or your veterinarian.

Q: What should owners do next? What should they tell their children?

A: Everyone handles grief differently, there is no one right way. Individuals need to ask themselves “what do I need.” This can be a difficult question to answer, and we may not be able to get what they need even if they figure it out, but we have a much better chance of getting what we need when we know what is needed. Talking to supportive people, engaging in activities that allow us to be present in the moment and staying out of our thoughts is a good place to start.

In regard to talking children, it is up to the family and their spiritual beliefs. It is an opportunity to have a conversation with them about what death is. Telling kids that their loved one is “getting put to sleep” can give children a negative association with sleep, and I recommend against it.

Q: Will pets that lose an animal as a companion grieve?

A: I am not an animal expert and really don’t know. It seems that the other pets do miss their companion and experience a loss, but I cannot say this with much validity.

Reactions of Other Pets in the Home

If you have other pets in your home, you might find that they appear to be grieving the loss of the one who died. This is not at all unusual as the loss of a human or animal family member will change the structure and dynamics of the family. Also, pets that have lived together can become just as bonded to each other as we become to them.

Therefore, many animals will experience a transitional and readjustment period as a reaction to the missing pet. If your pets are experiencing physical symptoms or behaviors that have you concerned, or if these symptoms last more than a couple of days to a week, a visit to your veterinarian is warranted to rule out illness or disease.

The following are some behaviors of surviving pets that have been reported by people:

• Searching behavior

• Increase or decrease in vocalization

• Changes in the amount of attention the pet wants

• Taking on behaviors of the pet that died even if this never occurred before, such as:

• Sleeping where the other pet slept

• Playing with toys that belonged to the pet that died

• Rubbing or rolling where the other pet rubbed or rolled

• Other unique activities the deceased pet engaged in

• Changes in appetite

• Changes in mood

• Personality changes such as quiet or shy pets becoming more outgoing and assertive, or outgoing pets becoming more quiet.

What You Can Do to Help Your Pets Through Their Grieving Process.

• Observe them closely for changes

• Do not change their basic routine or the structure of their day any more than is absolutely necessary. For example, feeding, grooming, and sleeping time should remain as close as possible to the way it was in the past. Remember, changes in your pet’s routine will only add to confusion.

• Respect your pet’s desire for “hands on” attention such as holding, cuddling and petting. Many people report wanting to get closer to remaining pets in the home but find that the pets do not always welcome more attention, especially if it is something they are not used to. Try not to push unwanted attention onto them. However, if remaining pets are seeking more close attention, then try to find the time to give it.

• Provide more opportunities for exercise and play — this will be good for both of you.

• Reward calm, relaxed or other desirable behavior.

• Try leaving a TV or radio on while you are gone.

• Understand that animals are very good at picking up on their human’s mood and some of your pet’s reactions could be a result of your stress or anxiety. Many people find it helpful to not cry or show extreme sadness in front of their pets.

Should You Get Another Animal as a Companion for Your Pet?

This is one of those questions for which you are the best person to answer. You know your pets better than anyone else and are most likely the one who knows best if another pet will make your current pet or pets feel better.

Some things you might want to consider when making this decision are:

• Is your pet very social?

• Is your pet used to having other animals around?

• Would another pet help your current pet to get more activity and exercise?

• If your current pet is now an only pet, how much time will it be spending alone if there is not another animal in the house?

• Are you and other family members ready to commit to and reinvest in another pet?

Things to Remember

• Some animals will show no signs of grief after the death of another pet in the house.

• Even for pets, grief is an individual process that will affect each one in a different way.

• Your pet’s reaction to the loss should improve as the days/weeks go by. If this does not happen or if anorexia (loss of appetite) occurs, then you should contact your veterinarian.

Q: Should a grieving pet owner get a replacement right away?

A: Again, this is a very personal decision without a right or wrong answer.

Q: Is there anything else in your experience that people frequently ask or encounter? How do you recommend they deal with it?

A: Be kind to yourself and allow the cycles of grief to run its course. It can take weeks, months, and even longer. Get support and take care of yourself best you can.

Below is an excerpt from our pet loss support page that I helped create:

Self-Care During the Grieving Process

Grief can affect every aspect of your being. Therefore, your emotional, physical, cognitive, social, and spiritual needs must be nurtured in order to work through grief and to heal.

The following are some suggestions on how you might begin the process of self-care. You may find that improving in one aspect makes you feel better in others, or that certain behaviors help in more than one area. This is because they cannot really be separated; each is somewhat dependent on the others and all are crucial in healing and maintaining your general good health.

Emotional

Emotional care involves expressing and acknowledging your pain.

• Talk with someone who understands the relationship you had with your pet and how much you are hurting

• Write down your feelings in a journal or in a letter to your loved-one

• Create a scrapbook or photograph album of your pet

• Use your artistic abilities such as drawing, painting, or sculpting to express your feelings.

Physical

Physical care is done to keep your body healthy.

Grief can deplete your energy and make you extremely susceptible to illness and disease.

• Eat healthy foods

• Exercise

• Avoid using alcohol or drugs as a means of “feeling better”

• Try to get enough sleep.

Cognitive

Cognitive functioning can be extremely impaired by grief.

Try stimulating yourself intellectually to improve your memory, concentration, and other cognitive abilities.

• Read books and other information that will help you to understand what you are going through

• Talk with others who have been through a similar experience and learn what was helpful for them

• Social contacts and establishing a support network are extremely important to help us not feel so alone.

• Find a healthy balance between the time you need alone and being with others

• Join a pet-loss support group

• Although not everyone will understand your grief, having a couple of close friends or family members who are supportive will help tremendously.

Spiritual

Spiritual care involves doing things that you enjoy, that connect you with nature, and being kind to yourself. Some people refer to this as working in your “heart zone.”

Spiritual care can, but does not have to, include your religious beliefs or your philosophy on life.

• Take a long walk

• Take a long bath or shower

• Light a candle in memory of your pet

• Get a massage, facial, pedicure, or anything that makes you feel good about yourself

• Think about your philosophy of an afterlife for animals and talk with others who believe similarly to you

• Call a friend you haven’t spoken with for a long time

• Do something kind for someone else

• Meditate

• Do something kind for other animals or for an animal cause.

Complete Article HERE!