by

Spoiler alert: You’re going to die. You already know that, but how much preparation for the inevitable have you made?

Living in Buncombe County, we can expect to live for 79.2 years, according to the local Health & Human Services Department. In a county with a quarter-million people, about 2,315 pass annually, an average based on 11,579 deaths in the five-year period from 2008–12, per a study by the department. The top three causes of death during those five years was cancer (2,563), heart disease (2,513) and chronic lower respiratory disease (784).

Last year was harder on us, though: 3,564 people died in Buncombe, the deputy registrar reports.

About 19 percent of Buncombe’s residents are 65 or older, according to 2015 U.S. census data — or 48,103 elders among a total population of 253,178. Of course, 65 is by no means the beginning of the end, nor does death target only the aged. In the five-year period covered by the above-cited study, we lost 170 people between the ages of 20 and 39, and 1,356 people between the ages of 40 and 64. And in 2015, we lost 176 people between the ages of 15 and 44 and 648 people between the ages of 45 and 64.

Given the ubiquitous and unavoidable nature of death, it seems that it should be an event we’d all plan for. But is it?

No one can confidently say that he will be living tomorrow — Euripides

Societal attitudes, traditions and responses toward death vary, but death is, well, as old as life. Carol Motley, founder of Bury Me Naturally Coffins and Caskets, says the advent of the Civil War and the resulting new practice of embalming was a catalyst for what American society now recognizes as a traditional funeral. “Before the war, you would dig a hole and put a body in it. During the Civil War, embalming tents became common at battlegrounds. You could get shipped home and not stink. And that was appealing,” she notes wryly.

Josh Slocum, executive director of the Funeral Consumers Alliance, agrees that the so-called traditional funeral is a relatively new concept. “We have a really short historical memory, but when you look back into the 19th century, what we now call a traditional funeral — the chemical embalming; the public display at a commercial place of business; mass-manufactured caskets; the Cadillac hearse to the cemetery — it didn’t come along until the last quarter of the 19th century,” he says. “It was a commercially created tradition.”

The FCA is a national nonprofit focused on raising awareness about consumer and legal rights when dealing with the funeral industry. “Most Americans, your own family, just a short period of time ago, was having a funeral where the body was washed at home, laid out at your home, in a coffin built by a local woodworker or by somebody in the backyard,” Slocum says. “That was the conventional burial. Burial in a sheet or wood box is as old as human history.”

Death is just another path, one that we all must take — J. R. R. Tolkien

While many people aren’t intentional about addressing their death, it’s a topic worth exploring, says Caroline Yongue, executive director of the Center for End of Life Transition. The interfaith organization helps people make decisions and provide instructions regarding what happens to their body after death. “North Carolina law says loved ones can act as funeral directors, so it is possible to bypass the funeral industry completely. But you would need to be prepared for death, to be prepared for what it takes to handle it yourself,” Yongue says. And planning ahead is key. “We’ve defaulted to the funeral industry in the last several decades, so people aren’t aware that they have their own legal rights,” she continues, noting that after a loved one dies, it’s difficult to know what to do if end-of-life decisions aren’t made beforehand.

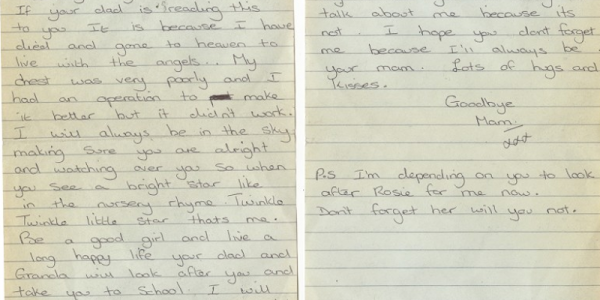

In many cases the deceased hadn’t been intentional about declaring wishes for their funeral and what they want to happen to their body, according to Yongue. Yet, there’s a comfort in not having to make those tough choices immediately after the last breath is declared: “A nurse or social worker walks in the room and asks, ‘Which funeral home do you want me to call?’ And the funeral home is called because that’s the path of least resistance.”

Motley concurs, saying that even those at the end of their path neglect the inevitable. “I can’t believe how many people are terminally ill, die and then we have to overnight a casket. Most of the time that’s what happens; you’re dealing with everything but the obvious,” she notes. “There’s not a place in our societal life where we address it. You have to make a concerted effort to do it. It’s not part of church, school, anything. And it should be. We should go ahead and fill out our death certificate.” You can get a death certificate in person, online or via mail, from the Buncombe County Register of Deeds.

Juanita Igo, a case manager with the Buncombe County Council on Aging, says she often sees that conversation placed on the back burner because of day-to-day stressors. “We work with people who don’t have enough resources to pay for their rent, their medication. … So sometimes just getting through the day is what they’re working on,” she notes.

Igo recommends using the Five Wishes document provided by the nonprofit Aging With Dignity. The document will help you determine what you want in regard to various aspects of medical and social preferences for the end of your life. “You’re taking people through a conversation that’s more natural to them, about what they want to have happen. Participants do have to get the form notarized, but it gets people thinking about those things and starts the conversation,” she says.

It’s not just the elderly who die, Igo adds. “It might be something that comes up suddenly, so it’s good to start the conversation.”

“Funeral planning has to be a family conversation, the same way we have conversations about where to go to college, how much it will cost and how we will pay for it,” says Slocum. He believes there is a distinctly American fear of death that keeps the subject irrationally inaccessible. “We don’t even like to say the word. If you look at the obituaries, and there’s 10 people in it, I bet you eight of them didn’t even die. They passed away, they went home to Jesus, but, by God, they didn’t die,” says Slocum.

The Rev. Ed Hillman, president of the FCA of Western North Carolina, also sees death as a taboo subject that needs to be brought into the light. “We don’t like to think about our own mortality. I think there’s an innate fear of death in all of us, and we think that somehow by talking about it, it will bring it about — which is not rational,” he says. Hillman points out that it’s everyone’s responsibility to have “the talk,” and that despite its uncomfortable nature, engaging the conversation can save anguish after a death. Unfortunately, “[not having the talk] can put our next of kin in a place where they have to guess what we want and end up spending resources that they might not even have in trying to figure out what a deceased person actually wanted,” he says. “The more detailed the plans, the less the next of kin has to guess about what the deceased person would want.”

Slocum says it also makes financial sense to determine your burial/cremation arrangements ahead of time. He urges people to approach this planning the same way they look for a car: Shop around. “Prices of funeral homes in the same city are wildly different. People don’t expect this. When you shop for a stereo, you’re shopping for a difference of price of about 35 percent; we don’t expect prices on the same model to range from $500 to $2,000. Not true at funeral homes,” he says. “You will find funeral homes, within driving distance of where you’re sitting right now, charging $1,000 for simple cremation and ones charging about $4,000 for that simple cremation.” The FCA of Western North Carolina compiles information about funeral costs in 14 counties. In Buncombe, the cost of cremation ranges from $895 to $4,460; and the cost of burial ranges from $1,495 to $6,940, with varying distances the funeral home will transport the body.

Slocum and Hillman make it clear that the FCA isn’t against the funeral industry. As Hillman notes, “The vast majority of funeral homes are really wonderful services for people, though every once in a while there are things people just do not need.” And Slocum adds that’s why the FCA’s mission is to educate consumers about their rights. “The Federal Trade Commission has the Funeral Rule that gives consumers important rights. You have the right to get quotes over the phone. Every funeral home you visit and talk about funeral arrangements with is required by law to hand you a printed, itemized price list at the beginning of the conversation,” he says. “Funeral homes are allowed to provide packages but they are not allowed to deny you itemized choices, and that’s one of the best ways to control funeral costs.”

Further, “Caskets, no matter what they’re made out of or how well they’re constructed, none of them will ‘protect or preserve your body.’ None of them will keep out air, water and dirt. None of them will keep you from decomposing,” Slocum notes. “There are caskets out there that are marketed as sealed and protective. And people of otherwise good sense can be misled. You’re going to be just as dead in a $10,000 casket as you are in a $2,500 cardboard box.”

As a well-spent day brings happy sleep, so life well-lived brings happy death — Leonardo da Vinci

But if a cardboard box is OK with you, there are ways to have a natural burial here in Western North Carolina. Yongue also runs the Carolina Memorial Sanctuary, an 11-acre plot of land that is the state’s first conservation burial ground. CMS has a conservation easement, and its burial techniques incorporate the chemical-free, unembalmed body, inside a biodegradable vessel, into the landscaping. “We all have a body, and it’s got to get recycled somehow. If we are conscientious about it, we can do it in a green way that has the least amount of impact on the planet,” she says. “Because we’ve got a lot of bodies on the planet.”

Yongue also doesn’t have anything bad to say about the funeral home industry. “Somebody’s got to deal with the bodies, but it’s incredibly expensive. And because people aren’t prepared, oftentimes they spend a lot more money than they would have if they had prepared for death,” she says. However, she knows unorthodox methods don’t always resonate. “Home funerals are not for everybody. Our hope is people become more informed about what their options are.”

Ultimately, Yongue believes, it’s about conveying postlife wishes, regardless of what those might be. Otherwise, she says, “It’s like going on a vacation, but you don’t plan for it. It would be like going to Europe, and the day of your trip arrives, you don’t have your passport, your luggage isn’t packed.”

Plus, a direct approach to death can have a positive effect on the living, Yongue posits. “If we walk around with death on our shoulder, we would be kinder, more compassionate, because everybody we see is going to die.”

Complete Article HERE!