Loss is a natural, but complex part of life.

Death and grief are natural parts of the human experience, but mourning a loss is also an incredibly complex process.

When a young child loses a loved one, parents often grapple with the challenge of explaining the concept of death and helping their little one through the grieving process (all while grieving themselves).

To help inform these difficult conversations, HuffPost spoke to a number of child mental health experts. Of course, a family’s cultural and religious background may steer the discussion, but there are certain guiding principles that are helpful for everyone to keep in mind.

Here are some expert suggestions for parents and caregivers when they prepare to talk about death and grief with children.

Be Honest And Straightforward

“Tell them the ‘facts’ about the death,” clinical psychologist John Mayer told HuffPost. “Don’t sugarcoat what death is or use ‘baby talk’ with a child. Do not use phrases like, ‘Grammy is sleeping.’ This is an opportune time to teach them about death. Don’t shy away from it.”

Board certified licensed professional counselor Tammy Lewis Wilborn echoed this sentiment, noting that using “cutesy language” and euphemisms in an attempt to protect kids from the realities of death and loss can actually do more harm than good.

“Children tend to think concretely, not abstractly, so when you use language that’s euphemistic, it can actually be more confusing or frustrating,” she explained. When people say things like “Dad is in the clouds” or “Your dad is taking a really long nap,” a young child may not understand the permanence of the fact that their father died and might even look for him in the clouds or expect him to wake up at some point.

Words like “death,” “died” or “dying” may sound harsh, but this is still developmentally appropriate language, Wilborn noted, and it’s important for children to have the language to understand the permanence of death.

Ask And Answer Questions

The kind of conversation a parent has with a child following the death of a loved one depends on the child’s relationship with the person who died. It should also vary based on the child’s developmental age and their understanding of what happens when someone dies. To that end, it’s useful to ask kids questions or offer to answer any questions they might have.

“Starting with questions can be a way in,” said Wilborn. “And you don’t necessarily need to give the specific details of how the person died, particularly if we’re dealing with traumatic grief. They don’t need all of the information, but they need enough age-appropriate details to understand that a person has died and isn’t coming back.”

Sometimes children may have witnessed something related to the loved one’s death, like being present at the scene of an accident or visiting the person in the hospital. In these cases, they need help understanding what they saw, said Chandra Ghosh Ippen, an expert in early childhood trauma and the associate director of the Child Trauma Research Program at the University of California, San Francisco.

Parents should try to shrink themselves down to the size of their child and walk through what they’ve experienced. Seeing someone in a hospital with tubes coming out of them or watching paramedics perform lifesaving procedures may be frightening for a small child, so it’s necessary for adults to appreciate how scary things might look to them.

“Create space for them to share how it might’ve affected them, and try to help them understand that doctors and paramedics were trying to help their loved one,” Ghosh Ippen explained.

It’s an ongoing conversation. “Young children will often come back to you after your very excellent explanation of death and still ask, ‘Am I going to see so-and-so?’” Ghosh Ippen said. “It’s not that they didn’t understand you, but little kids tend to repeat their questions. It’s sort of their way of mulling it over and making meaning. This can be painful for caregivers, but appreciate that the child did hear you and is just having a difficult time wrapping their head around the concept of death.”

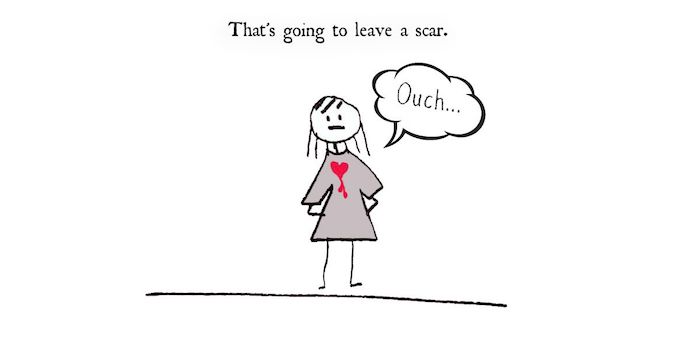

Know That Their Emotions Are Complicated

“Grief is a complex process, so it comes with a range of thoughts, emotions and behaviors,” Wilborn explained. While parents may expect their child to feel sad, angry, confused or even guilty about a loss, there are other behavioral changes that can be harder to understand, like changes in sleeping and eating patterns or school performance issues.

Sometimes parents may feel confused about a perceived lack of sadness in their kids. “Young children have a short sadness span,” said Ghosh Ippen. “A child can suffer a devastating loss and feel really sad, and then they can go play. You may be thinking, ‘Were they really affected by what happened?’”

While adults tend to immobilize and sink into sadness, kids often discharge it by running around or trying to do something else. “They kind of go in and out of sadness, and that can put us at odds with them if we’re thinking, ‘Oh, my God, do they not care?’” she continued. “But recognize that they did care.”

Be Patient

Wilborn noted that grief is a long process, so parents should reject the tendency to want to rush past it and wonder when their kids are going to be over it.

“Grief is a process that you cannot go around. You have to go through it. So you need to be OK with the pace of the process,” she said. “It can take some time for a child to return to his or her normal.”

Mayer emphasized the power of this experience and of talking to kids about death as a way to build major developmental coping skills. “This is a positive and helps them cope with loss in their life in the future and even transitions in their life, such as leaving one school to another, advancing to high school or college, and losing relationships.”

Encourage Expression

“Children need to see that their parents are a resource; home is a resource where grief is welcome,” Wilborn said, noting that parents should encourage age-appropriate expressions of grief.

“For example with a school-aged, play is their language, so you want to lean into ways that children play to promote communication ― things like drawing pictures, playing games, dolls, puppet shows at home,” she added. “With older kids, you might encourage them to journal, draw, write songs, create poems.”

Mayer noted that being a resource for your child creates a sense of safety and security that will serve them in later life events. “They know they can depend on you, and it is wonderful modeling for them.”

Create Rituals

Creating rituals around remembering and honoring a loved one who died is another significant form of expression. “Explain that this person may not be here with us, but we can still remember him or her and celebrate their life as a family,” said Wilborn.

“When the death is really traumatic, sometimes caregivers stop talking about the person who died,” Ghosh Ippen explained. “And what’s hard in those cases is that children lose their ‘angel memories’ ― times when they really felt loved and cared for with that person. It’s normal for grown-ups in mourning to find it hard to talk about the person who died, but it’s important to memorialize them.”

Many cultures and religions promote rituals around saying goodbye and making meaning of death. Mayer noted that losing a loved one presents an opportunity for parents who have religious belief systems to explain these tenets to their children.

“Religious or not, it is also very helpful to teach your children that all the experiences and memories you have had with this loved one do not get erased with their death. People always live in our hearts and our minds forever, and no one or nothing can take that away,” he explained. “Say something like, ‘Where’s Aunt Susie right now? She’s not in this room with us right now, correct? That doesn’t mean she doesn’t exist.’ Aunt Susie is here (point to your head) and here (point to your heart). We have to keep our memories and good times with Aunt Susie alive.”

Make Sure They Know It’s Not Their Fault

“Sometimes children have this really uncanny way of assigning blame to themselves for things that have nothing to do with them,” said Wilborn.

With that in mind, caregivers need to help kids understand that the death is in no way their fault, and it’s not their responsibility to put on a strong face or hide their feelings.

Use Books And Other Resources

There are many great resources for parents navigating this difficult topic with their children. Ghosh Ippen and Wilborn both recommend Sesame Street’s online grief toolkit, which provides talking points, videos, activities, storybooks and more. Ghosh Ippen and Wilborn also pointed to the National Child Traumatic Stress Network as another great source of online resources.

Ghosh Ippen maintains Pinterest boards with book recommendations, including one on loss, grief and traumatic bereavement. Some of her favorite children’s books that tackle these topics include Chester Raccoon and the Acorn Full of Memories, The Dragonfly Door, When Dinosaurs Die: A Guide to Understanding Death, Rosie Remembers Mommy: Forever in Her Heart, Sad Isn’t Bad: A Good-Grief Guidebook for Kids Dealing With Loss and Samantha Jane’s Missing Smile: A Story About Coping With the Loss of a Parent.

As far as books for parents, Mayer recommended the writings of psychiatrist Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, as well as How Do We Tell the Children? Fourth Edition: A Step-by-Step Guide for Helping Children and Teens Cope When Someone Dies and Understanding and Supporting Bereaved Children: A Practical Guide for Professionals.

Beyond books and online resources, Wilborn emphasized the value of community resources, such as school counseling, support groups, play therapy and peer counseling.

Let Them See You Grieve

The way a child’s parents or caregivers respond to a loss is instrumental in helping them cope. “They need to see you grieve,” said Wilborn. “But they also need to see you taking care of yourself and engaging in self-care, which may or may not include professional help. If you don’t, they may feel like they have to take care of you because you’re not managing grief in a way that’s healthy.”

It’s OK to cry in front of your children and show the value of expressing emotions and having shared emotions among family members. It’s OK to say things like “I’m feeling really sad because my dad died” or “Daddy is sad because he misses his mom.”

“Within our culture, we often have a sense that we have to be tough, so many parents are trying to help their kids by putting on a brave or overly cheery face,” said Ghosh Ippen. “But that can seem really odd and confusing. The child is feeling sad because it’s devastating that this person is gone, but then the parent is cheery ― which can feel eerie and weird.”

Ultimately, it’s about conveying the idea that “Mom is sad, and Mom is also strong,” she continued. If the feelings of grief become overwhelming, parents should seek help from other sources because it’s not their child’s role to help them.

“It’s important for little kids to believe that grown-ups are bigger, wiser and stronger,” said Ghosh Ippen. “We are not going to fall apart, and if we are going to fall apart, other grown-ups are going to help us.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Gilbert reflects on the death of her partner, Rayya Elias — her longtime best friend, whose sudden terminal cancer diagnosis unlatched a trapdoor, as Gilbert put it, into the realization that Rayya was the love of her life:

Gilbert reflects on the death of her partner, Rayya Elias — her longtime best friend, whose sudden terminal cancer diagnosis unlatched a trapdoor, as Gilbert put it, into the realization that Rayya was the love of her life: