— Alua Arthur on her ancient profession

Death anxiety and end-of-life planning are all in a day’s work for a care worker who helps shepherd clients off this mortal coil

There is little about Alua Arthur that emanates the deathly or morbid. The 45-year-old Los Angeles resident has a radiant, gap-toothed smile, a propensity for citrus-colored nail polish and an inclination to laugh before she finishes a sentence.

But not long ago, she was a Legal Aid worker struggling with depression, frequently taking breaks to travel around the world, attend music festivals, visit friends and enjoy short-lived romances with fellow searchers. While backpacking in Cuba, she boarded a bus and sat next to a woman around her age who revealed that she had been diagnosed with uterine cancer. What followed was an hours-long conversation that sent her world off its axis.

“It was strangely intimate and comfortable and hilarious,” Arthur said. “There was such an ease in our new friendship that allowed us to travel to the depths together, and discuss our fears and hopes.” Not long after she came home, her brother-in-law was dying of cancer, and she threw herself into caring for him, her sister and her then four-year-old niece.

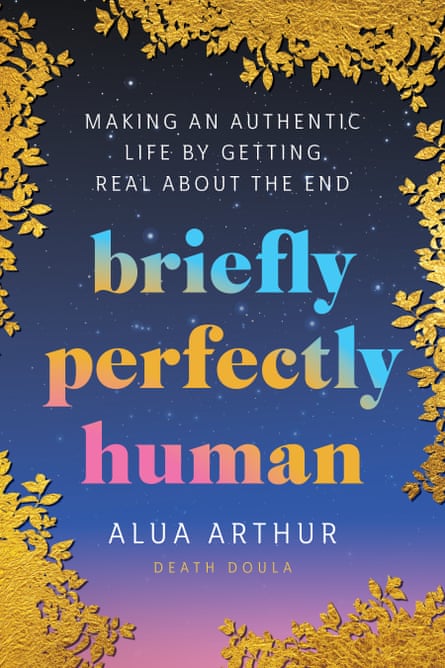

Within a few months, she followed her gut and enrolled in a training program to become a death doula, an end-of-life care worker who helps people tie up their affairs and feel more at ease as they face the inevitable. The job can involve providing company, talking through clients’ feelings about estranged friends and family members, and helping them look back on their lives and identify the moments of which they are proud and also their regrets. It’s a calling that Arthur, who grew up in Colorado as the daughter of political refugees from Ghana, details in her rousing memoir, Briefly Perfectly Human.

A celebratory spirit pervades the book. The flip side of thinking about death all day, after all, is remembering how fleeting life is and relishing the mere act of living, as well as the people and natural beauty that surrounds us. Arthur, whose company, Going With Grace, has trained over 2,500 death professionals in 17 countries, spoke with the Guardian about her end-of-life work.

The death doula seems to be gaining popularity, on the heels of the birth doula. Do you sense that we will be hearing about death doulas more and more?

The death doula is very ancient, because as long as humans have been alive, they’ve been dying, and others have been supporting them into their dying. But the profession and the formality of it have been rising in the modern world. It’s similar to birth doulas in the concept and in the work that we do – we care for and celebrate one another. But there’s now a Fortune 500 company that has a death doula benefit as part of their benefits program, where employees get reimbursed to seek the services of a doula for somebody that they consider family. They can help be supportive for somebody’s dying and get reimbursed. Isn’t that pretty rad?

You talk a lot in your book about the difference between empathy and compassion. Can you walk me through that?

I’ve been really empathic all my life. I feel things very deeply. And I feel that I’m feeling things on behalf of other people, but also what I’m feeling for them are things that I’ve made up in my head about what the experience is like. And when I’m doing that when somebody is dying, it’s really dangerous because I don’t know what it’s like to be dying. I can imagine it all I want, but I don’t know what it’s like, and that can be really problematic. This may be a little rude, but I feel like empathic people, sometimes we’re pretty self-aggrandizing in some way. What we have to do when we’re working with people that are dying is practice lucid compassion, which says: I don’t know what it is that you’re experiencing, but I’m down. I’m here with you, and I’ll ride with you.

What does a typical week in your work life look like?

I’m not seeing clients currently – I’m way too busy. These days I’m focusing on spreading public awareness about how we die, hoping to help more people get support when they’re dying, and honestly help more death doulas get clients. But when I was seeing clients, I would have probably just one client whose death looks like it’s coming soon, and then multiple end-of-life-planning clients. And I’d also be doing death meditations, and hosting workshops and helping healthy people plan for the end of life, and helping somebody who has a serious illness.

So not all of your clients count as end-of-life patients?

Many clients are people that carry a lot of death anxiety. There was one client who I met with maybe for two years. His mom had died and his death anxiety was through the roof after she died. And so once a week for almost two years, he would sit and talk about where death anxiety popped up in his life that week, and we’d work through it. I’d offer tips and tricks and we’d do exercises. There was one young woman, she was 22 years old and her parents were in their 50s. But she just thought that it’d be wise to do end-of-life planning and I thought, oh, cool. Let’s do it.

There is a trend in our culture to fetishize the “birth story” but people back off from discussing death, let alone the “death story”.

We want to pretend that it’s not happening. And yet it’s happening every day, all around us. Not only in nature, but there’s probably somebody a few doors down from your home who knows somebody who’s in the process of dying. And we don’t have any skills to talk about our experience. We don’t make space for grief.

But I feel like it’s starting to shift. For example, this television series, Limitless, with Chris Hemsworth. In one of the episodes he explores the limits of his physical body. Even though the previous episodes were all about how he could live longer and better, a whole one is thinking about death.

Our world is lousy with biohackers trying to stave off death.

We can’t escape it. That’s kind of the point. People work so hard to create all these workarounds and try to deny it in some capacity. But by denying it, they’re making it more real. Like, why not just spend the time talking about your fears of death?

In your book you don’t hold back about your battle with depression. How does that inform your work?

Well, for starters, my life prior to death care was just kind of a hot mess. There was no direction, no purpose, but there was plenty of adventure. I was the lawyer working at Legal Aid and who was broke, saddled in debt. Prior to death care, I was always seeking something – you know, something that made me feel alive. I sought out big adventures, traveled to faraway places, ate different foods. I used to go to Burning Man but I haven’t been recently. I think that part of me has always been seeking peak experiences in life. That part of me lends itself really, really easily to death care because a big part of my relationship to death is grounding myself in this body of this life for now, and filling it up as much as I can.

What’s the number one question people ask you when they’re dying?

They always ask what the meaning of it all is. And I don’t know! I know that maybe the locs and the dark skin and the jewelry make people think that I’m talking to other beings all the time, that I’m mystical. But I don’t know anything.

Two of my friends recently lost their parents and I’ve been struggling with writing letters to them. Do you have any advice?

Sometimes the right thing to do is just to show up and say, like, “This is really, really hard but I don’t know what to say, but just know that I care about you. Just know that I know this happened. I don’t know what you’re experiencing. And this is uncomfortable, but I want you to know that I’m here and I care about you.” And then you’ll probably get a thank-you, and if they want to talk about the person they lost, they will, and if they want to talk about the Kardashians, they will.

How does your current work influence the way you live now?

I think I give myself a lot more grace for the mistakes I make and my sadness and my fear and my doubt, and the extra pounds that I’m carrying. I give myself a lot more freedom to enjoy food. Whereas before, I was so concerned with being skinny and exercising, and now I’m like, fuck it, like I’m so grateful for this body that carries me around Earth. Plus, I love chocolate cake.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!