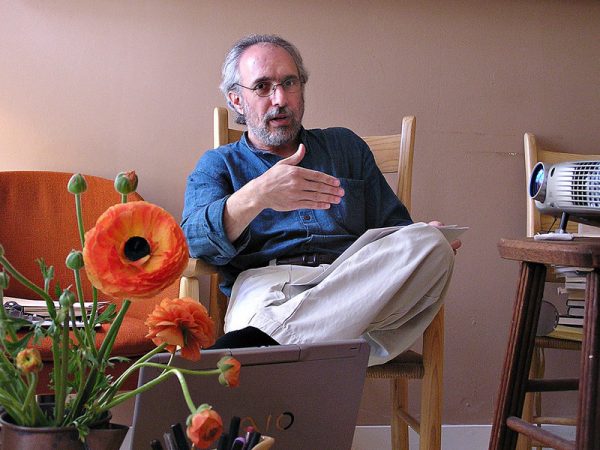

Dr. Lonny Shavelson heads Bay Area End of Life Options, a Berkeley, Calif., medical practice that offers advice and services to patients seeking aid in dying under the state law enacted last June.

By JoNel Aleccia

[I]n the seven months since California’s aid-in-dying law took effect, Dr. Lonny Shavelson has helped nearly two dozen terminally ill people end their lives with lethal drugs — but only, he says, because too few others would.

Shavelson, director of a Berkeley, Calif., consulting clinic, said he has heard from more than 200 patients, including dozens who were stunned to learn that local health care providers have refused to participate in the state’s End of Life Options Act.

“Those are the ones who could find me,” says Shavelson, who heads Bay Area End of Life Options and is a longtime advocate of assisted suicide. “Lack of access is much more profound than anyone is talking about.”

Across California, and in the five other states where medical aid-in-dying is now allowed, access is not guaranteed, advocates say. Hospitals, health systems and individual doctors are not obligated to prescribe or dispense drugs to induce death, and many choose not to.

Most of the resistance comes from faith-based systems. The Catholic Church has long opposed aid-in-dying laws as a violation of church directives for ethical care. But some secular hospitals and other providers also have declined.

In Colorado, where the nation’s latest aid-in-dying law took effect in December, health systems covering nearly third of hospitals in the state, plus scores of clinics, are refusing to participate, according to a recent STAT report.

Even in Oregon, which enacted the first Death with Dignity law in 1997, parts of the state have no providers within 100 miles willing or able to dispense the lethal drugs, say officials with Compassion & Choices, a nonprofit group that backs aid-in-dying laws.

“That’s why we still have active access campaigns in Oregon, even after 20 years,” says Matt Whitaker, the group’s state director for California and Oregon. “It becomes a challenge that causes us to have to remain extremely vigilant.”

In Washington state, where the practice was legalized in 2009, a Seattle hospice patient with advanced brain cancer was denied access to willing providers, so he shot himself in the bathtub, according to a 2014 complaint filed with the state health department.

“Refusing to provide information or appropriate referrals directly led to the unnecessarily violent death of this patient,” said the complaint filed by an anonymous hospice nurse. “I strongly believe this constitutes patient abandonment.”

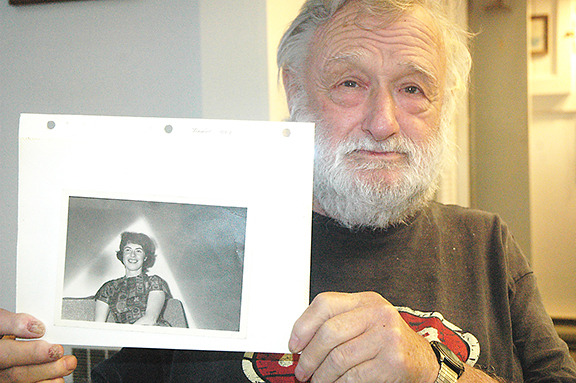

Lack of access was also an issue for Annette Schiller, 94, of Palm Desert, Calif., who was diagnosed with terminal thyroid and breast cancer and wanted lethal drugs.

“Almost all of her days were bad days,” recalled Linda Fitzgerald, Schiller’s daughter. “She said, ‘I want to do it.’ She was determined.”

Schiller’s hospice turned down her request, and she couldn’t find a local referral, forcing Linda Fitzgerald to scramble to fulfill her mother’s last wish.

“I thought it was going to be very simple and they would help us,” says Linda Fitzgerald. “Everything came up empty down here.”

Annette Schiller of Palm Desert, Calif., who was 94 and diagnosed with terminal thyroid and breast cancer, had trouble finding doctors to help her end her life under California’s new aid-in-dying law.

Opponents of aid in dying cite providers’ reluctance as evidence that the laws are flawed and the practice is repugnant to a profession trained to heal.

“People consider it a breaking of professional integrity,” says Dr. David Stevens, chief executive of Christian Medical & Dental Associations, which has worked to stop or overturn aid-in-dying laws in several states.

But those decisions can effectively isolate people in entire regions from a legal procedure approved by voters, advocates said.

In California’s Coachella Valley, where Annette Schiller lived, the three largest hospitals — Eisenhower Medical Center, Desert Regional Medical Center and John F. Kennedy Memorial Hospital — all opted out of the new state law. Affiliated doctors can’t use hospital premises, resources or systems in connection with aid in dying, hospital officials said.

“Eisenhower’s mission recognizes that death is a natural stage of the life journey and Eisenhower will not intentionally hasten it,” Dr. Alan Williamson, vice president of medical affairs of the non-profit hospital, said in a statement.

Doctors may provide information, refer patients to other sources or prescribe lethal drugs privately, Williamson said.

“All we have done is say it can’t be done in our facility,” he added.

In practice, however, that decision has had a chilling effect, says Dr. Howard Cohen, a Palm Springs hospice doctor whose firm also prohibits him from writing aid-in-dying prescriptions or serving as an attending physician.

“They may be free to write for it, but most of them work a full day. When and how are they going to write for it?” he said. “I don’t know of anyone here who is participating.”

Patients eligible for aid-in-dying laws include terminally ill adults with six months or less to live, who are mentally competent and can administer and ingest lethal medications themselves. Two doctors must verify that they meet the qualifications.

Many doctors in California remain reluctant to participate because of misunderstandings about what the law requires, says Dr. Jay W. Lee, past president of the California Academy of Family Physicians.

“I believe that there is still a strong taboo against talking about death openly in the medical community. It feels like a threat to what we are trained to do: preserve and extend life,” Lee says, adding that doctors have a moral obligation to address end-of-life concerns.

There’s no single list of doctors willing to prescribe life-ending drugs, though Compassion & Choices does offer a search tool to find participating health systems.

“They don’t want to be known as the ‘death docs,’ ” says Shavelson, who has supervised 22 deaths and accepted 18 other people who were eligible to use the law but died before they could, most within a required 15-day waiting period.

Officials with Compassion & Choices said past experience indicates that more providers will sign on as they become more familiar with the laws and their requirements.

At least one California provider, Huntington Hospital in Pasadena, originally said it wouldn’t participate in the law, but later changed its position.

Other health systems have opted to not only participate, but also to help patients navigate the rules. Kaiser Permanente, which operates in California and Colorado, has assisted several patients, including Annette Schiller, who switched her supplemental insurance to Kaiser to receive the care.

Within weeks, Schiller was examined by two doctors who confirmed that she was terminally ill and mentally competent. She received a prescription for the lethal drugs. On Aug. 17, she slowly ate a half-cup of applesauce mixed with Seconal, a powerful sedative.

“Within 20 seconds, she fell asleep,” her daughter recalled. “Within a really short time, she stopped breathing. It was amazingly peaceful.”

Complete Article HERE!