Religious Muslims in many nations are finding their sacred rituals of mourning disrupted.

By George Yancy

This month’s conversation in our series on how various religious traditions deal with death is with Leor Halevi, a historian of Islam, and a professor of history and law at Vanderbilt University. His work explores the interrelationship between religious laws and social practices in both medieval and modern contexts. His books include “Muhammad’s Grave: Death Rites and the Making of Islamic Society” and “Modern Things on Trial: Islam’s Global and Material Reformation in the Age of Rida, 1865-1935.” This interview was conducted by email and edited. The previous interviews in this series can be found here.

— George Yancy

George Yancy: Before we get into the core of our discussion on death in the Islamic faith, would you explain some of the differences between Islam and the other two Abrahamic religions, Christianity and Judaism?

Leor Halevi: Like Judaism and Christianity, Islam is a religion that has been fundamentally concerned with divine justice, human salvation and the end of time. It is centered around the belief that there is but one god, Allah, who is considered the eternal creator of the universe and the omnipotent force behind human history from the creation of the first man to the final day. Allah communicated with a long line of prophets, beginning with Adam and ending with Muhammad. His revelations to the last prophet were collected in the Quran, which presents itself as confirming the Torah and the Gospels. It is not surprising, therefore, that there are many similarities between the scriptures of these three religions.

There are also intriguing differences. Abraham, the father of Ishmael, is revered as a patriarch, prophet and traveler in Islam, Christianity and Judaism. But only in the Quran does he appear as the recipient of scrolls that revealed the rewards of the afterlife. And only in the Quran does he travel all the way to Mecca, where he raises the foundations of God’s house.

As for Jesus, the Quran calls him the son of Mary and venerates him as the messiah, but firmly denies his divinity and challenges the belief that he died on the cross. A parable in the Gospels suggests that he will return to earth for the judgment of the nations. The Quran also assigns him a critical role in the last judgment, but specifies that he will testify against possessors of scriptures known as the People of the Book.

Some of these alternative doctrines and stories might well have circulated among Jewish or Christian communities in Late Antiquity, but they cannot be found in either the Hebrew Bible or the New Testament. The differences matter if salvation depends on having faith in the right book.

Yancy: I assume that for Islam, we were all created as finite and therefore must die. How does Islam conceptualize the inevitability of death?

Halevi: The Quran assures us that every death, even an apparently senseless, unexpected death, springs from God’s incomprehensible wisdom and providential design. God has predetermined every misfortune, having inscribed it in a book before its occurrence, and thus fixed in advance the exact term of every creature’s life span. This sense of finitude only concerns the end of life as we know it on earth. If Muslims believe in the immortality of the soul and in the resurrection of the body, then they conceive of death as a transition to a different mode of existence whereby fragments of the self exist indefinitely or for as long as God sustains the existence of heaven and hell.

Yancy: What does Islam teach us about what happens at the very moment that we die? I ask this question because I’ve heard that the soul is questioned by two angels.

Halevi: This angelic visit happens right after the interment ceremony, which takes place as soon as possible after the last breath. Two terrifying angels, whose names are Munkar and Nakir, visit the deceased. In “Muhammad’s Grave,” I described them as “black or bluish, with long, wild, curly hair, lightning eyes, frighteningly large molars, and glowing iron staffs.” And I explained that their role is to conduct an “inquisition” to determine the dead person’s confession of faith.

Yancy: What does Islam teach about the afterlife? For example, where do our souls go? Is there a place of eternal peace or eternal damnation?

Halevi: The soul’s destination between death and the resurrection depends on a number of factors. Its detachment from a physical body is temporary, for in Islamic thought a dead person, like a living person, needs both a body and a soul to be fully constituted. Humans enjoy or suffer some sort of material existence in the afterlife; they have a range of sensory experiences.

Before the resurrection, they will either be confined to the grave or dwell in heaven or hell. The spirit of an ordinary Muslim takes a quick cosmic tour in the time between death and burial. It is then reunited with its own body inside the grave, where it must remain until the blowing of the trumpet. In this place, the dead person is able to hear the living visiting the grave site and feel pain. For the few who earn it, the grave itself is miraculously transformed into a bearable abode. Others, those who committed venial sins, undergo an intermittent purgatorial punishment known as the “torture of the grave.”

Opinion Today: Get expert analysis of the news and a guide to the big ideas shaping the world.

Prophets, martyrs, Muslims who committed crimes against God and irredeemable disbelievers fare either incomparably better or far, far worse. Martyrs, for instance, are admitted into Paradise right after death. But instead of dwelling there in their mutilated or bloodied bodies, they acquire new forms, maybe assuming the shape of white or green birds that have the capacity to eat fruit.

For the final judgment, God assembles the jinn, the animals and humankind in a gathering place identified with Jerusalem. There, every creature has to stand, naked and uncircumcised, before God. In the trial, prophets and body parts such as eyes and tongues bear witness against individuals, and God decides where to send them. Throngs of unbelievers are then marched through the gates of hell to occupy — for all eternity, or so the divines usually maintained — one or another space between the netherworld’s prison and the upper layers of earth. Those with a chance of salvation need to cross a narrow, slippery bridge. If they do not fall down into a lake of fire, then they rise to heaven to enjoy, somewhere below God’s throne, never-ending sensual and spiritual delights.

Yancy: What kind of life must we live, according to Islam, to be with Allah after we die?

Halevi: The answer depends on whom you ask to speak for Islam and in what context.

A theologian might leave you in the dark but clarify that the goal is not the fusion of a human self with the divine being, but rather a dazzling vision of God.

A mystic might tell you that the essential thing is to discipline your body and soul so that you come to experience, if only for a fleeting moment, a taste or foretaste of the divine presence. Among other things, she might teach you to seek a state of personal annihilation or extinction, where you surrender all consciousness of your own self and of your material surroundings to contemplate ecstatically the face of God.

Your local imam might tell you that beyond professing your belief in the oneness of God and venerating Muhammad as the messenger of God, you ought to observe the five pillars of worship and repent for past sins. Paying your debts, giving more in charity than what is mandated and performing extra prayers could only help your chances.

A jihadist in a secret chat room might promise your online persona that no matter how you lived before committing yourself to the cause, if you beg for forgiveness and die as a martyr, you will at the very least gain freedom from the torture of the grave.

As a historian, I refrain from giving religious advice. Muslims have envisioned more than one path to salvation, and their ideals, which we might qualify as Islamic, have changed over time. Remember, for example, that in Late Antiquity and the Early Islamic period, ascetics engaged in prolonged fasts, mortification of the flesh and sexual renunciation for the sake of salvation. This was a compelling path back then. Now it is a memory.

Yancy: If one is not a Muslim, what then? Are there consequences after death for not believing or for not being a believer?

Halevi: Belief in the possible salvation of virtuous atheists and virtuous polytheists would be difficult to justify on the basis of the Muslim tradition.

But there is a variety of opinions about your question among contemporary Muslims who profess to believe in heaven and hell. Exclusive monotheists, those advocating a narrow path toward salvation, say that every non-Muslim who has chosen not to convert to Islam after hearing Muhammad’s message is likely to burn in hell. Exceptions are made for the children of infidels who die before reaching the age of reason and for people who live in a place or time devoid of exposure to the one and only true religion. On the day of judgment, these deprived individuals will be questioned by God, who may decide to admit them into heaven.

What about Mother Teresa and the Dalai Lama? Will saints and spiritual leaders also meet a dire end? This is sheer speculation but I imagine that a high percentage of Muslims, if polled about their beliefs, would readily declare that nobody can fathom the depths of Allah’s mercy and that righteous individuals should be saved on account of their good deeds.

In the late 20th century, a few prominent Muslim intellectuals, yearning for a more inclusive and pluralistic approach to religion, drew inspiration from a Quranic verse to argue that Jews and Christians who believe in one God, affirm the doctrine of the last day and do works of righteousness will also enter Paradise.

Yancy: Does Islam teach its believers not to fear death?

Halevi: I am not convinced that it effectively does that. Or that teaching believers to deal with this fear is a central aim. Arguably, many religious narratives about death and the afterlife are supposed to strike dread in our hearts and thus persuade us to believe and do the right thing. Even if a believer arrogantly presumes that God will surely save him, still, he may have to face Munkar and Nakir, contend in the grave with darkness and worms, stand before God for the final judgment and cross al-Sirat, the bridge over the highest level of hell. All of this sounds quite terrifying to me.

Of course, I realize that Sufi parables may suggest otherwise. Like the poet Rumi, who fantasized about dying as a mineral, as a plant and as an animal to be reincarnated into a better life, some Sufi masters imagined dying so vividly and so often that they allegedly lost this fear.

What Islamic narratives do teach believers is not to protest death, especially to accept the death of loved ones with resignation, forbearance and full trust in God’s wisdom and justice.

Yancy: Would you share with us how the dead are to be taken care of, that is, are there specific Islamic burial rituals?

Halevi: Instead of giving you a short and direct answer, I would like to reflect a little on how the current situation, the coronavirus pandemic, is making it difficult or impossible to perform some of these rites. Locally and globally, limits on communal gatherings and social distancing requirements have devastated the bereft, making it so very difficult for them to receive religious consolation for grief and loss.

In every family, in every community, the death of an individual is a crisis. Funeral gatherings cannot repair the tear in the social fabric, but traditional rituals and condolences were designed to send the dead away and help the living cope and mourn. The pandemic has of course disrupted this.

In Muslim cultures, the corpse is normally given a ritual washing and is then wrapped in shrouds and buried in a plot in the earth. Early on during the pandemic, concerns that the cadavers of persons who died from Covid-19 might be infectious led to many adaptations. Funeral homes had to adjust to new requirements and recommendations for minimizing contact with dead bodies. And religious authorities made clear that multiple adjustments were justified by the fear of harm.

In March of 2020, to give one example, an ayatollah from Najaf, Iraq, ruled that instead of thoroughly cleaning a corpse and perfuming it with camphor, undertakers could wear gloves and perform an alternative “dry ablution” with sand or dust. And instead of insisting on the tradition of hasty burials, he ruled that it would be fine, for safety’s sake, to keep corpses in refrigerators for a long while.

In the city of Qom, Iran, the coronavirus reportedly led to the digging of a mass grave. It is not clear how the plots were actually used. But burying several bodies together in a single grave would not violate Islamic law. This extraordinary procedure has long been allowed during epidemics and war. By contrast, burning a human body is regarded as abhorrent and strictly forbidden. For this reason, there was an outcry over Sri Lanka’s mandatory cremation of Muslim victims of the coronavirus.

Every year on the 10th day of the month of Muharram, Shiites gather to lament and remember the martyrdom of al-Husayn ibn Ali, the third Imam and grandson of Muhammad the Prophet. This year Ashura, as the day is known, fell in late August. It is a national holiday in several countries. Ordinarily, millions gather to participate in it. This year, some mourned in crowds, in defiance of government restrictions and clerical advice; others contemplated the tragic past from home and perhaps joined live Zoom programs to experience the day of mourning in a radically new way.

It is far from clear today if, when the pandemic passes, the old ritual order will be restored or reinvented. One way or the other, there will be many tears.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Day of the Dead: How Ancient Traditions Grew Into a Global Holiday

What began as ceremonies practiced by the ancient Aztecs evolved into a holiday recognized far beyond the borders of Mexico.

By Iván Román

The Day of the Dead or Día de Muertos is an ever-evolving holiday that traces its earliest roots to the Aztec people in what is now central Mexico. The Aztecs used skulls to honor the dead a millennium before the Day of the Dead celebrations emerged. Skulls, like the ones once placed on Aztec temples, remain a key symbol in a tradition that has continued for more than six centuries in the annual celebration to honor and commune with those who have passed on.

Once the Spanish conquered the Aztec empire in the 16th century, the Catholic Church moved indigenous celebrations and rituals honoring the dead throughout the year to the Catholic dates commemorating All Saints Day and All Souls Day on November 1 and 2. In what became known as Día de Muertos on November 2, the Latin American indigenous traditions and symbols to honor the dead fused with non-official Catholic practices and notions of an afterlife. The same happened on November 1 to honor children who had died.

Day of the Dead Traditions

In these ceremonies, people build altars in their homes with ofrendas, offerings to their loved ones’ souls. Candles light photos of the deceased and items left behind. Families read letters and poems and tell anecdotes and jokes about the dead. Offerings of tamales, chilis, water, tequila and pan de muerto, a specific bread for the occasion, are lined up by bright orange or yellow cempasúchil flowers, marigolds, whose strong scent helps guide the souls home.

Copal incense, used for ceremonies back in ancient times, is lit to draw in the spirits. Clay molded sugar skulls are painted and decorated with feathers, foil and icing, with the name of the deceased written across the foreheads. Altars include all four elements of life: water, the food for earth, the candle for fire, and for wind, papel picado, colorful tissue paper folk art with cut out designs to stream across the altar or the wall. Some families also include a Christian crucifix or an image of the Virgin of Guadalupe, Mexico’s patron saint in the altar.

In Mexico, families clean the graves at cemeteries, preparing for the spirit to come. On the night of November 2, they take food to the cemetery to attract the spirits and to share in a community celebration. Bands perform and people dance to please the visiting souls.

“People are really dead when you forget about them, and if you think about them, they are alive in your mind, they are alive in your heart,” says Mary J. Andrade, a journalist and author of eight books about the Day of the Dead. “When people are creating an altar, they are thinking about that person who is gone and thinking about their own mortality, to be strong, to accept it with dignity.”

Celebrating the Dead Becomes Part of a National Culture

Honoring and communing with the dead continued throughout the turbulent 36 years that 50 governments ruled Mexico after it won its independence from Spain in 1821. When the Mexican Liberal Party led by Benito Juárez won the War of Reform in December 1860, the separation of church and state prevailed, but Día de Muertos remained a religious celebration for many in the rural heartland of Mexico. Elsewhere, the holiday became more secular and popularized as part of the national culture. Some started the holiday’s traditions as a form of political commentary. Like the funny epitaphs friends of the deceased told in their homes to honor them, some wrote calaveras literarias (skulls literature)—short poems and mock epitaphs—to mock living politicians or political criticism in the press.

“This kind of thing happens alongside the more intimate observation of the family altar,” says Claudio Lomnitz, an anthropologist at Columbia University and author of Death and the Idea of Mexico. “They are not in opposition to one another.”

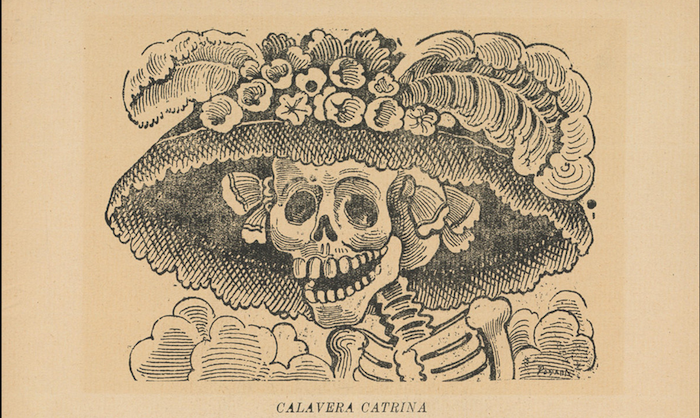

The Rise of La Catrina

In Mexico’s thriving political art scene in the early 20th century, printmaker and lithographer Jose Guadalupe Posada put the image of the calaveras or skulls and skeletal figures in his art mocking politicians, and commenting on revolutionary politics, religion and death. His most well-known work, La Calavera Catrina, or Elegant Skull, is a 1910 zinc etching featuring a female skeleton. The satirical work was meant to portray a woman covering up her indigenous cultural heritage with a French dress, a fancy hat, and lots of makeup to make her skin look whiter. The title sentence of his original La Catrina leaflet, published a year before the start of the Mexican Revolution in 1911, read “Those garbanceras who today are coated with makeup will end up as deformed skulls.”

La Catrina became the public face of the festive Día de Muertos in processions and revelry. Mexican painter Diego Rivera placed a Catrina in an ostentatious full-length gown at the center his mural, completed in 1947, portraying the end of Mexico’s Revolutionary War. La Catrina’s elegant clothes of a “dandy” denote a mocking celebration, while her smile emerging through her pompous appearance reminds revelers to accept the common destiny of mortality.

Skulls of Protest, Witnesses to Blood

Over decades, celebrations honoring the dead—skulls and all—spread north into the rest of Mexico and throughout much of the United States and abroad. Schools and museums from coast to coast exhibit altars and teach children how to cut up the colorful papel picado folk art to represent the wind helping souls make their way home.

In the 1970s, the Chicano Movement tapped the holiday’s customs with public altars, art exhibits and processions to celebrate Mexican heritage and call out discrimination. In the 1980s, Day of the Dead altars were set up for victims of the AIDS epidemic, for the thousands of people who disappeared during Mexico’s drug war and for those lost in Mexico’s 1985 earthquake. In 2019, mourners set up a giant altar with ofrendas, or offerings, near a Walmart in El Paso, Texas where a gunman targeting Latinos killed 22 people.

As Lomnitz explains, one reason why more and more people may be taking part in Día de Muertos celebrations is that the holiday addresses a reality that is rarely acknowledged by modern cultures—our own mortality.

“It creates a space for communication between the living and the dead. Where else do people have that?” Lomnitz says. “These altars have become a resource and connection to that world and that’s part of their popularity and their fascination.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

How Can We Bear This Much Loss?

In William Blake’s engravings for the Book of Job I found a powerful lesson about grief and attachment.

By Amitha Kalaichandran

If grief could be calculated strictly in the number of lives lost — to war, disease, natural disaster — then this time surely ranks as one of the most sorrowful in United States history.

As the nation passes the grim milestone of 200,000 deaths from Covid-19 — only the Civil War, the 1918 flu pandemic and World War II took more American lives — we know that the grieving has only just begun. It will continue with loss of jobs and social structures; routines and ways of life that have been interrupted may never return. For many, the loss may seem too swift, too great and too much to bear, each story to some degree a modern version of the biblical trials of Job.

I thought of the biblical story of Job last month when I was asked to speak to the National Partnership for Hospice Innovation. How would I counsel others to cope with losses so terrifying and unfair? How could those grieving find a sense of hope or meaning on the other side of that loss?

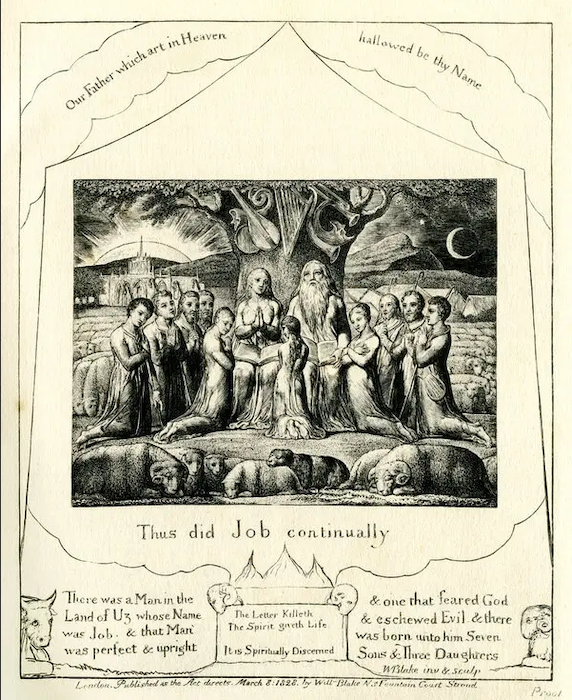

In my research I found myself drawn to the powerful rendition of the Book of Job by the 18th-century British poet, artist and mystic William Blake, in particular his collection of 22 engravings, completed in 1823, that include beautiful calligraphy of biblical verses.

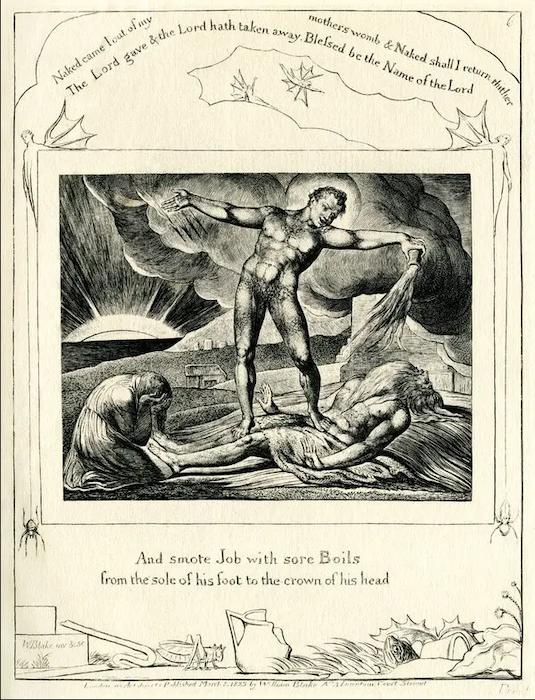

Job, of course, is the Bible’s best-known sufferer. His bounty — home, children, livestock — is taken cruelly from him as a test of faith devised by Satan and carried out by God. He suffers both mental and physical illness; Satan covers him in painful boils.

Job is conflicted — at times he still has his faith and trusts in God’s wisdom, and other times he questions whether God is corrupt. Finally, he demands an explanation. God then allows Job to accompany him on a tour of the vast universe where it becomes clear that the universe in which he exists is more complex than the human mind could ever comprehend.

Though Job still doesn’t have an explanation for his suffering, he has gained some peace; he’s humbled. Then God returns all that Job has lost. So, the story is, in large part, about the power of one man’s faith. But that’s not all.

The verses Blake chooses to inscribe on his illustrations suggest there’s more. In the first engraving we see Job’s abundance. Plate 6 includes the verse: “Naked came I out of my mother’s womb, and naked shall I return thither: The Lord gave, and the Lord hath taken away.”

So, the Book of Job isn’t just about grief or just about faith. It’s also about our attachments — to our identities, our faith, the possessions and people we have in our lives. Grief is a symptom of letting go when we don’t want to. Understanding that attachment is the root of suffering — an idea also central to Buddhism — can give us a glimpse of what many of us might be feeling during this time.

We can recall the early days of the pandemic with precision; rites that weave the tapestry of life — jobs, celebrations, trips — now canceled. In our minds we see loved ones who will never return. Even our mourning is subject to this same grief, as funerals are much different now.

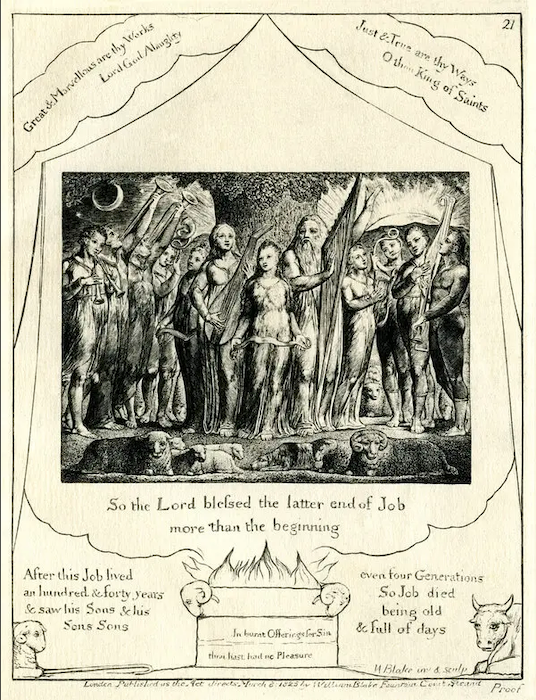

In Blake’s penultimate illustration in this series Job is pictured with his daughters. Notably Blake doesn’t write out this verse from Job; instead he writes something from Psalm 139: “How precious also are thy thoughts unto me, O God! How great is the sum of them!” In the very last image, however, God has returned all he had taken from Job — children, animals, home, health and more. Here, Blake encapsulates Job 42:12: “So the Lord blessed the latter end of Job more than his beginning: for he had 14,000 sheep, and 6,000 camels, and 1,000 yoke of oxen, and 1,000 donkeys.”

Blake intentionally didn’t make the last image a carbon copy of the first, likely in order to reflect new wisdom: an understanding that we are more than just our attachments. The sun is rising, trumpets are playing, all signifying redemption. Job became a fundamentally changed man after being tested to his core. He has accepted that life is unpredictable and loss is inevitable. Everything is temporary and the only constant, paradoxically, is this state of change.

So, where does all of this leave us now, as we think back to how our attachments have fueled our grief, but perhaps also our faith in what’s to come? Can we look forward to a healthier, more just world? Evolution can sometimes look like destruction to the untrained eye.

I think it leaves us with a challenge, to treat our attachments not simply as the root of suffering but as fuel that, when lost, can propel us forward as opposed to keeping us tethered to our past. We can accept the tragedy and pain secondary to our attachments as part of a life well lived, and well loved, and treat our memories of our past “normal” as pathways to purpose as we move forward. We still honor our old lives, those we lost, our previous selves, but remain open to what might come. Creating meaning from tragedy is a uniquely human form of spiritual alchemy.

As difficult as it is now, in the midst of a pandemic, it is possible — in fact, probable — that after this cycle of pain we feel as individuals and collectively that we might emerge with a greater understanding of ourselves, faith (if you’re a person of faith), and our purpose.

The word “healing” is derived from the word “whole.” Healing then is a return to “wholeness” — not a return to “sameness.” Those who work in hospice know this well — the dying can be healed in the act of dying. But we don’t typically equate healing with death.

Ultimately, to me, that’s the lesson offered by Blake’s Job: understanding his role in a wider universe and cosmos, transformed in his surrender, and the release from the attachments to his old life. Job had the benefit of journeying across the universe to understand his life in a larger context.

We don’t. But we do have the benefit of being his apprentices as we begin to emerge from this period, and begin to choose whether it propels us forward or keeps us stuck in pain, and in the past.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

This was how Santa Muerte was adopted by Mexican culture

The cult of the skeletal image, as it is practiced today, emerged in the middle of the 20th century, but has its antecedents in the viceregal period, according to the anthropologist Katia Perdigón.

According to the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH), the cult of Santa Muerte is known today for their prayers and the veneration of the skeletal image, which you might think was adopted into Mexican culture. However, it has a long history in Mexico.

In an interview that the INAH conducted with the anthropologist Katia Perdigón, she says that Santa Muerte has its antecedents from colonial times. Although for many the word «death» is a taboo that when mentioning it produces silence, admiration and fear.

The doctor in Social Anthropology, and a pioneer in studies on Santa Muerte, mentioned that this “icon comes from macabre dances and some Greco-Latin designs, hence the presence of the scythe, the mantle and the balance, to mention a few elements ”.

By the 19th century, the followers managed to separate their ideologies and there were some who decided to continue preparing for the “good to die” and continued to worship the image of death.

Since the Colony, it was sought to evangelize devotees and converts so that they had a «good death». Reason why at that time you could see large sculptures with the skeletal image that went out in procession on Good Friday. Of these great sculptures, at least three are preserved in the country: the Holy Death of Yanhuitlán, which is visited in the former Dominican convent of that Oaxacan town; and known as San Bernardo and San Pascual Bailón, in Tepatepec, Hidalgo, and Tuxtla Gutiérrez, Chiapas, respectively, said Katia.

«In colonial times, the Catholic Church saw this veneration as heresy towards the skeletal image of death. According to inquisitorial documents from the 17th and 18th centuries that I was able to consult, retaliation was not directed at the people involved, but at the action itselfEven in 1797 a chapel was razed to the ground in the town of San Luis de la Paz, where this cult was practiced, ”said Perdigón Castañeda.

By the 19th century, the followers managed to separate their ideologies and there were some who decided to continue preparing for the «Good to die» and they continued to worship the image of death.

“Thus a totally different iconography emerged, for example, the macabre dances and the representation of the Triumph of Death turned into something else, in such a way that they are retaken to carry out political mockery, this was started by the cartoonist Gabriel Vicente Gahona (‘Picheta’) in the southeast, and years later José Guadalupe Posada did it, with the image of La Catrina ”.

According to the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH), the cult of Santa Muerte is known today for its prayers and veneration of the skeletal image, which one might think was adopted into Mexican culture.

«The same,» the anthropologist continued. (Santa Muerte) housewives approach her, that doctors or policemen; However, at the end of the nineties, yellow fever has linked its cult to outlaw groups or people who live or work in the streets, after it was reported that the kidnapper Daniel Arizmendi, alias “El Mochaorejas”, captured in that decade, He was devoted to the image.

The researcher concluded that this devotion that arose in the center of the country has already reached the borders (north and south) and even crossed the Atlantic Ocean, since in European countries all the iconography of Santa Muerte is retaken as an element of art kitsch.

Why the celebration of Santa Muerte on the Day of the Dead

Consider that this mixture of beliefs related to more current religions, found a place on November 2 and that the idea of this day celebrating the dead is already ingrained in the collective consciousness.

Endoveliko, who is a follower of Santa Muerte, says that in Ecatepec Santa Muerte is celebrated because it was on those dates, 17 years ago, that the Congregation that began to organize in the area. Each altar celebrates its anniversary on a different date, and they wanted to take advantage of the Mexican celebration to combine it with their foundation.

He believes that both parties are related: remembering the deceased and venerating Santa Muerte are ideas that have always been combined, Endoveliko considers. “Our celebration is eminently from here because since prehistory so much of Europe and here in America, peoples have always worshiped death with different names, different languagesHere, death was worshiped from the Olmecs, Teotihuacán, the Mexica ”, he explained.

But believe that for a while it went out and tried to silence this cult. Although with the freedom of ideologies in the Mexican Constitution, these beliefs reappeared.

Consider that this mixture of beliefs related to more current religions, found a place on November 2 and that in the collective consciousness The idea of this day celebrating the dead is already ingrained.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

The surprising benefits of contemplating your death

Now is the perfect time to face your fear of mortality. Here’s how.

Nikki Mirghafori has a fantastically unusual career. After getting a PhD in computer science, she’s spent three decades as an artificial intelligence researcher and scientific advisor to tech startups in Silicon Valley. She’s also spent a bunch of time in Myanmar, training with a Buddhist meditation master in the Theravada tradition. Now she teaches Buddhist meditation internationally, alongside her work as a scientist.

One of Mirghafori’s specialties is maranasati, which means mindfulness of death. Mortality might seem like a scary thing to contemplate — in fact, maybe you’re tempted to stop reading this right now — but that’s exactly why I’d say you should keep reading. Death is something we really don’t like to think or talk about, especially in the West. Yet our fear of mortality is what’s driving so much of our anxiety, especially during this pandemic.

Maybe it’s the prospect of your own mortality that scares you. Or maybe you’re like me, and thinking about the mortality of the people you love is really what’s hard to wrestle with.

Either way, I think now is actually a great time to face that fear, to get on intimate terms with it, so that we can learn how to reduce the suffering it brings into our lives.

I recently spoke with Mirghafori for Future Perfect’s limited-series podcast The Way Through, which is all about mining the world’s rich philosophical and spiritual traditions for guidance that can help us through these challenging times.

In our conversation, Mirghafori outlined the benefits of contemplating our mortality. She then walked me through some specific practices for developing mindfulness of death and working through the fear that can come up around that. Some of them are simple, like reciting a few key sentences each morning, and some of them are more … shall we say… intense.

I think they’re all fascinating ways that Buddhists have generated over the centuries to come to terms with the prospect of death rather than trying to escape it.

You can hear our full conversation in the podcast here. A partial transcript, edited for length and clarity, follows.

Sigal Samuel

You’ve worked in Silicon Valley and you still live near there, so I’m sure you’ve encountered the desire in certain tech circles to live forever. There are biohackers who are taking dozens of supplements every day. Some are getting young blood transfusions, trying to put young people’s blood in their veins to live longer. Some are having their bodies or brains preserved in liquid nitrogen, doing cryopreservation so they can be brought back to life one day. What is your feeling about all these efforts?

Nikki Mirghafori

It’s the quest for immortality and the denial of death. Part of it is natural. Human beings have done this for as long as we have been conscious of the fact that we are mortal.

A person who really put this well was Ernest Becker, the author of the seminal book The Denial of Death. I’d like to offer this quote from him:

This is the paradox. A human is out of nature and hopelessly in it. We are dual. Up in the stars and yet housed in a heart-pumping, breath-gasping body that once belonged to a fish and still carries the gill marks to prove it. A human is literally split in two. We have an awareness of our own splendid uniqueness in that we stick out of nature with a towering majesty, and yet we go back into the ground a few feet in order to blindly and dumbly rot and disappear forever. It is a terrifying dilemma to be in and to have to live with.

There is a whole field of research in psychology called terror management theory, which started from the work of Ernest Becker. This theory says that there’s a basic psychological conflict that arises from having, on the one hand, a self-preservation instinct, and on the other hand, that realization that death is inevitable.

This psychological conflict produces terror. And how human beings manage this terror is either by embracing cultural beliefs or symbolic systems as ways to counter this biological reality, or doing these various things — cryogenics, trying to find elixirs of life, taking lots of supplements or whatnot.

It’s nothing new. The ancient Egyptians almost 4,000 years ago, and ancient Chinese almost 2,000 years ago, both believed that death-defying technology was right around the corner. The zeitgeist is not so different. We think we are more advanced, but it comes from the same fear, same denial of death.

Sigal Samuel

It seems like in the West, we really have a bad case of that denial. I think we rarely talk about death or are willing to face up to the reality that we’re going to die. We seem to be wanting to always distract ourselves from it.

You are a Buddhist practitioner and you have a practice that is very much the opposite of that, which is mindfulness of death, or maranasati. You’ve done trainings and led retreats around this subject. But some people might say this is too morbid and depressing to think about. So before we actually delve into the mindfulness of death practices, could you entice us by telling us a few of the benefits of doing them?

Nikki Mirghafori

First and foremost, what I found for many people, myself included, is that facing the fact that I am not going to live forever really aligns my life with my values.

Most people suffer what’s called the misalignment problem, which is that we don’t quite live according to our values. There was a study that really highlighted this, by a team of scientists, including Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman. They surveyed a group of women and compared how much satisfaction they derived from their daily activities. Among voluntary activities, you’d probably expect that people’s choices would roughly correlate to their satisfaction. You’re choosing to do it, so you’d think that you actually enjoy it.

Guess what? That wasn’t the case. The women reported deriving more satisfaction from prayer, worship, and meditation than from watching television. But the average respondent spent more than five times as long watching television than engaging in spiritual activities that they actually said they enjoyed more.

This is a misalignment problem. There’s a way we want to spend our time, but we don’t do that because we don’t have the sense that time is short, time is precious. And the way to systematically raise the sense of urgency — Buddhism calls it samvega, spiritual urgency — is to bring the scarcity of time front and center in one’s consciousness: I am going to die. This show is not going to go on forever. This is a party on death row.

Sigal Samuel

So the approach here is to bring to the forefront of our consciousness how precious our time is, by impressing upon our minds how scarce it is. And that helps align our life with our values.

Are there other benefits to practicing mindfulness of death?

Nikki Mirghafori

The second benefit is to live without fear of death for our own sake. That way, we don’t engage in typical escape activities. And it frees up a lot of psychic energy. We have more peace, more ease in our lives.

The third benefit is to live without fear of death for the sake of our loved ones. We can support others in their dying process. Usually the challenge of supporting a loved one is that we have a sense of grief for losing them, but a lot of that grief is actually that it’s bringing up fear of our own mortality. So if we have made peace with our own mortality, we can be fully present and support them in their process, which can be a huge gift.

My mom passed away two years ago. And for me, having done all of these practices, I could be with her by her deathbed, holding her hand and supporting her so that she could have a peaceful transition. She didn’t have to take care of me so much and console me. She could be at peace and take delight in this mysterious process that we just don’t know what it’s like. It might be beautiful, might be graceful. We don’t know — there might be nothing; there might be something.

Sigal Samuel

Now I feel sufficiently enticed to learn about the actual practices of mindfulness of death. Let’s start with one that seems simple: the Five Daily Reflections, sometimes called the Five Remembrances, that are often recited in Buddhist circles. Would you mind reciting those?

Nikki Mirghafori

Happy to. These are the Five Daily Reflections that the Buddha suggested people recite every day.

Just like everyone, I am of the nature to age. I have not gone beyond aging.

Just like everyone, I am of the nature to sicken. I have not gone beyond sickness.

Just like everyone, I am subjected to the results of my own actions. I am not free from these karmic effects.

Just like everyone, I am of the nature to die. I have not gone beyond dying.

Just like everyone, all that is mine, beloved and pleasing, will change, will become otherwise, will become separated from me.

Allow whatever arises to come up. It’s okay. These contemplations can bring a lot up. So just be with them as much as possible.

Sigal Samuel

I’ve done these reflections before, but every time I do them, I notice that some are much harder for me to absorb than others. The fourth one — I’m of the nature to die — does not terrify me. Maybe that’s weird, but that’s not the one that really scares me. The one that I find impossibly hard is the fifth one. Everyone that I love and everything that I love is of the nature to change and be separated from me.

It’s really the death or the separation from the people I love that I find much harder to face than the death of myself. Because if I’m going to die, you know, then I’ll be gone. There won’t be any me to miss things.

Nikki Mirghafori

Yes. So appreciate and make space for the one that really touches you.

Also I would say that with the fourth one, making peace with our own death, I’ve done the practice and sometimes I’m like yeah, sure, whatever. And then I’ve really stayed with it, and thought, “This could be my last breath.” When the practice really takes hold and becomes alight with fire, it’s like, “Oh, my God, I am going to die!” It really hits home.

Sigal Samuel

Just to clarify, this is a separate mindfulness of death practice, where you contemplate with every breath, “This could be my last inhale. This could be my last exhale.”

Nikki Mirghafori

Yes. And to bring the historical context into it: This particular teaching is what’s called maranasati. Marana is death in Pali, the language of the Buddha. Sati is mindfulness. The mindfulness of death sutra, that’s where the Buddha taught it, and it’s actually quite a lovely teaching.

The Buddha comes and asks the monks, “How are you practicing mindfulness of death?” And one of them says, “Well, I think I could die in a fortnight, in a couple weeks.” Another one of them says, “Well, I think I could die in 24 hours.” Or “Well, I could die at the end of this meal.” Or “Well, I could die at the end of this bite of food I’m eating.” And another one says, “Well, I could die at the end of this very breath.”

And the Buddha says, “Those of you who said, two weeks, 24 hours, whatever — you are practicing heedlessly. Those who said right at this breath, you are practicing heedfully, correctly. That is the practice.”

There are ways to really bring the sense of immediacy and urgency to all this. It’s not out of the question that there could be an aneurysm or that a meteor could just hit the Earth in this moment. Use visualizations; be creative.

Sigal Samuel

Another thing I find really helpful is remembering the idea of impermanence. Which, of course, is the theme of our whole conversation — that our whole life is impermanent — and that’s a very central Buddhist teaching. But also any emotion that I’m feeling is impermanent. So if I’m feeling an intense surge of fear as I do a practice, that’s impermanent, too.

Nikki Mirghafori

Yeah, I love that. When I teach impermanence, there are little impermanences that come and go, and then there is the big impermanence, which is your life! I’m chuckling because this is a case where impermanence is on your side. Impermanence is just a rule of how things run in this world. It’s impersonal. It’s just the way things are. But in our perspective, it’s either working for us or against us.

Sigal Samuel

Can you tell me about another kind of contemplation — the “corpse contemplation” or “charnel ground contemplation”? Charnel grounds are these places where, after people have died, their bodies are left to decay above ground, to rot in the open air. And Buddhist monks would go and observe them up close, right?

Nikki Mirghafori

Many monks do that, especially in Asia. In order to become more intimate with a sense of mortality, the practice is to go to the charnel ground and to actually see a corpse. And the contemplation is: My body, this alive body, is just like this body that is decaying. It’s in different stages of being a body, of decomposing.

A specific practice in the Buddhist canon is to contemplate a corpse in different stages of decay. This particular practice requires a sense of stability of mind. Do the other ones first. I only teach it on a retreat when there’s a container of safety, holding people and supporting them through it.

Sigal Samuel

I definitely have not yet worked myself up to doing corpse contemplation by looking at images of actual human corpses. But when I go for a walk, whenever I see a dead bird or squirrel or mouse that’s been run over in the road, I actually pause and take a minute to look at it. I’m trying to ease my way into this practice.

Nikki Mirghafori

Brilliant. Similarly, another informal practice I wanted to share is having a memento mori. Like a little skull, or those bracelets that are all skulls. I just drew on a little Post-It a skull and bones, and posted it on my computer monitor, so I would remember: Life is short. I’m going to die.

I’ve had various memento moris on my desk throughout the years, and I invite people to have them. They don’t have to be sophisticated. On a piece of paper, just write out, “Life is short” or “You are going to die” or “Traveler, tread lightly.” Whatever works for you to keep death in your perspective. And I think it’s good to switch memento moris around so that your mind doesn’t get used to seeing the same thing all the time.

Sigal Samuel

I’m glad you brought this up because I was going to say the corpse contemplation reminds me a lot of that memento mori tradition, which is a centuries-long tradition in Christianity. So many different religious traditions have emphasized the importance of meditating on our death and have devised ways like the memento mori to try to keep forcing the ego to recognize its looming demise.

Nikki Mirghafori

Yes. And I know that for me, I feel most alive and I feel happiest and I feel most connected with myself, when I’m aware of my death. If it happens for a day or two that it’s not in the forefront for whatever reason, I’m not as bright, as sharp, as alive. So I just love bringing it back. It enlivens me. It supports me to live more fully and hopefully die with more delight and joy and curiosity.

Sigal Samuel

I’m wondering if you can help me with something else. I mentioned earlier that I’m not really scared of my own death so much, but I am scared of the death of the people I love. And especially during the pandemic, I think that’s causing a lot of anxiety for me and probably a lot of others. We’re scared about the potential death of our grandparents, our parents, our friends. Is there a way to free ourselves of the overwhelming fear of their death?

Grief is a natural part of the process. However, it is complicated by our own seen and unseen fear of death. So I invite you to actually work with the practice of making peace with your own death. That’s what’s underlying it. Even if you think you’re not afraid of your own death, you probably are.

When people are really at peace with their own passing, there is a different perspective. There’s a different way of being with the fear or sadness of losing others. There is still a pain of loss, but it shifts.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Why ceremony matters

By Lois Heckman

Creating ceremonies is what I do, and every once in a while it’s good to stop and remember why. To my way of thinking, there are three really big transitions in life: birth, death and marriage. Every culture and religion, all around the world, has different ways to honor these milestones. Momentous occasions are honored and celebrated in diverse ways, almost always involve ceremony; rites of passage.

Elizabeth Gilbert wrote: “Ceremony is essential to humans: It’s a circle that we draw around important events to separate the momentous from the ordinary. And ritual is a sort of magical safety harness that guides us from one stage of our lives into the next, making sure we don’t stumble or lose ourselves along the way.”

That really nails it. I probably don’t have to even say anymore. But naturally I will!

Besides those three big ones, other life changing transitions include coming of age, sexual identity, and any major disruption in relationships— especially divorce. All are deserving of recognition, in small or big ways. We also have ceremonies for graduation or receiving awards and even retirement.

Each tradition has its own way to express the meaning, with specific rituals, readings or actions. And let’s remember that cultures and traditions evolve, changing with the times, or struggling to do so.

Perhaps you have heard of one of the most unusual coming-of-age ceremonies. It takes place in a remote island in the South Pacific, where boys risk their lives jumping head-first from a 90-foot tall wooden tower with nothing but vines wrapped around their ankles. Yes, ceremony can take many forms.

While I specialize in honoring weddings (what I think of as the No. 3 spot in the all-important life changes challenge) I also officiate funerals, baby welcomings and occasionally other types of events. I recently performed a lovely renewal of vows, and I have also created interesting anniversary celebrations, blessing of animals, and community events. I even create secular confirmation programs and ceremonies.

A funeral or memorial service is another important milestone. Sometimes people choose to do something a few weeks or more after the person has died. It can be somewhat more uplifting, and also allows people time to make plans to travel. These are often called a “celebration of life” rather than a funeral. But some traditions do not allow for this. Devout Jews and Muslims are required to bury almost immediately after the death. However, this still wouldn’t preclude a celebration of the person at a later date, after the burial.

I know there are times when families skip a formal ceremony for the dead. The reasons for this are varied. Sometimes it is a discomfort with religion, especially if the deceased had given up on her or his faith, or the family has a mixture of beliefs and they are unsure how to handle that.

There could be costs that make it prohibitive or seem wasteful to the survivors.

There might be family dysfunction and no one wants to come together, especially if it feels like you are honoring someone who was not a good person. We know how people always say nice things about the dead, even if they don’t deserve it. These are tricky issues, but if you loved the person who has died, even without a formal ceremony, it is worthwhile to take some special time to honor that loss. As we often hear (and rightly so) — a funeral is for the living

Weddings are entirely different. Even elopements deserve to be properly honored. A wedding is a joyful time and the ceremony is meant to move everyone through this transition. The wedding ceremony honors the partner’s separate lives, their past, and the journey that led them to one another, then marks the moment of commitment, and takes them into their future as they walk down the aisle, beginning a new path, side by side.

Even for couples who have been together for years, it is still important. Getting married is meaningful at any time or stage in one’s life. There are so many good reasons to marry, including legal rights and science has shown that a healthy marriage promotes better and longer lives. And let’s remember if the couple getting married has children, it is also an important moment for them.

Big changes have always deserved recognition, and I believe they always will. I hope everyone realizes the importance of taking the time to do just that, in whatever way works for you. And of course, I’m happy to help if you need me.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!

Emptiness and Filling Out Forms:

A Practical Approach to Death

Dying with compassion means having a plan in place for those left behind. A practitioner recounts how she navigated the process with her dharma friends.

By Rena Graham

As a Tibetan Buddhist practitioner, I am constantly reminded that we never know when death might approach, but for years, I’d avoided dealing with one of the most practical aspects of death—the paperwork. I was not alone: Roughly half of all adults in North America do not have a living will. Then recently, I suffered a near-fatal illness that left me viscerally aware of how unprepared for death I was, and I made a pledge with two of my friends to get ready to leave our bodies behind for both ourselves and the people who survive us.

Bridging the end of December 2017 and the beginning of January 2018, I spent a month in a Vancouver, British Columbia hospital with a bacterial lung infection that had also invaded my pleural cavity—the first time I’d come down with a severe illness. After ten days in an intensive-care unit, I was moved to a recovery ward where I suffered a relapse. I spent my 62nd birthday, Christmas, and New Years with strangers in the hospital.

One night in the ICU, while I was partly delirious and falling in and out of sleep, I had a vision of a deceased friend reaching out to me. From what felt like disengaged consciousness, I looked down at my body on the hospital bed and realized I wasn’t ready to die. I hadn’t studied my lama’s [teacher’s] bardo teachings to navigate the intermediate state between death and rebirth, and did not want to take that journey without a road map. It didn’t matter whether this was a drug-fueled hallucination or an actual near-death experience. The important thing is that I rejected death, not out of fear, but through a recognition of the dreamlike nature of reality. After this experience, I felt that my attachment to this life and the things in it had diminished. I no longer wanted to ignore what came next. I wanted to be prepared.

When I told my friends Liv and Rosie about this vision, we agreed to study the bardo teachings together once I’d had a couple of months of recuperation. By March, however, our plans shifted. Rosie had heard about a man (I’ll call him Ben) who had died on Lasqueti Island, an off-the-grid enclave in Canada’s Southern Gulf Islands that a local cookbook once described as “somewhere between Dogpatch and Shangri-La.” He had left his closest friends without any instructions. They had no idea if he had a family or where they might be.

“And he left an old dog behind!” Rosie said, “Can you imagine?”

“Not the bodhisattva way to die,” I replied, referring to the Buddhist ideal of compassion. I also imagined what mess I might have left, had I not made it.

Promising they would never leave others in such a quandary, Ben’s closest friends created a document called the Good to Go Kit, which detailed information required for end-of-life paperwork. (It is now sold at the Lasqueti Saturday market to raise funds for their medical center.)

“I’ve been wanting to make a will for 20 years,” said Liv, who would soon turn 70, “but research throws me into information overload, which adds to the emotional overwhelm I feel just thinking about it.”

“What if we did this together instead of studying the bardo?” suggested Rosie, who was in her early 50s.

Writing a will, figuring out advanced healthcare directives, and noting our final wishes didn’t have the mystical lure of bardo teachings, but we set that aside for a year while we took on this more practical area of inquiry.

To use our time wisely, we set several parameters in place. We decided to meet one weekend a month to allow time for research and reflection between meetings, and we chose to keep our group small for ease of scheduling and to allow us to delve deeper into each topic.

“I’d like this to be structured,” said Liv, “so it doesn’t devolve into a social event.”

Rosie and I agreed but we knew better than to believe there didn’t need to be some socializing. She offered her place for the first meeting and said she’d cook.

“We’ll get our chit-chat out of the way over dinner,” she said. “Since we can all be a little intimidated by this process, we have to make it fun.”

Later in March at Rosie’s garden suite, we sat down to dinner and Liv passed out copies of “A Contemplation of Food and Nourishment,” which begins with the appropriate words: “All life forms eat and are eaten, give up their lives to nourish others.” The prayer was written by Lama Mark Webber, Liv and Rosie’s teacher in the Drikung Kagyu school. (I also study with Lama Mark, although my main teacher, Khenpo Sonam Tobgyal, is in the Nyingma lineage.) Turning our meetings into sacred practice seemed the obvious container to keep us on topic.

After dinner, Rosie rang a bell, we said a refuge prayer and recited the traditional four immeasurables prayer to generate equanimity, love, compassion, and joy toward all sentient beings.

We traded our prayers for notebooks and reviewed our Good to Go Kit. Rosie smiled at the expected question of pets—including the name of the person who would be caring for the pet, the veterinarian and whether money had been set aside for their expenses. The form also asked whether we had hidden items or buried treasure.

Liv laughed and said, “People still bury strongboxes in their backyards?”

My answer was more prosaic: “Storage lockers.”

Rosie, Liv, and I are all single and childless. We are all self-employed and independent and have chosen Canada as our adopted homeland, meaning we have no family here. So we considered what roles friends might play and focused on those who were closer geographically than sentimentally.

Pulling them in to act on our behalf seemed like such a “big ask” as Rosie said, but it was time to get real about our needs. The three of us shared our feelings about involving friends outside the dharma versus those within.

When I was in the ICU, my friend Diane visited on several occasions and later told me she remained calm until she reached her car, where she cried uncontrollably. In marked contrast, my dharma friend Emma calmly asked what I needed and didn’t make much of a fuss. My Buddhist friends tend to view death as a natural transition from one incarnation to the next, while other friends may see it in more dire terms: as a finality or even failure. For end-of-life situations, asking non-Buddhist friends for limited practical support seemed kinder for all involved.

We started to familiarize ourselves with the responsibilities of someone granted power of attorney for legal and financial proxy and enduring power of attorney for healthcare. Months later, we agreed our network of “dharma sisters” would be the perfect fit. While we hope to maintain our ability to make decisions for ourselves, should we require long-term care, we felt the baton could be passed between a dozen or so trustworthy women. We have since spoken casually about this with a number of these women and have made plans to organize a get-together and discuss our plans in greater detail, offering reciprocal support for what the Buddhist author Sallie Tisdale calls “the immeasurable wonder and disaster of change.”

We concluded our five hours together by dedicating the merit and reciting prayers of dedication and aspiration. Long-life prayers for our lamas were offered, a bell rung, and heads bowed. Without the need for further conversation, we made our way into the chilly spring evening, silently reflecting on our new endeavor.

The next meeting and those following included menus and discussions that varied widely. Our research grew monthly with documents from government agencies, legal and trust firms, and funeral homes. None of which felt specific to Buddhist practitioners, until Rosie told us about Life in Relation to Death: Second Edition by the late Tibetan teacher Chagdud Tulku Rinpoche. This small book is out of print, but I purchased a Kindle copy. In the introduction, Chagdud Tulku, a respected Vajrayana teacher and skilled physician, reminds us that “[t]here are many methods, extraordinary and ordinary, to prepare for the transformation of death.” A book of Buddhist “pith instruction,” it includes in its second edition appendices that above all I found most valuable. These include suggested forms for “Durable Power of Attorney for Health Care,” “Advance Directive for Health Care (Living Will),” “Miscellaneous Statements for Witnesses, Notary and Physician,” and “Letter of Instructions.” It even includes a wonderful note for adding your ashes to tza-tsas, small sacred images stamped out of clay. We loved that idea, though we couldn’t imagine asking friends to go to that extent to honor our passing.

We decided to use a community-based notary public to draw up our wills, but with further research, Liv realized she could also hire them to act as her executor, rather than use her bank. She found someone experienced and enjoyed the more personable experience. In contrast, Rosie and I’ve decided to pay friends now that we’ve found ways to simplify that process for them.

Memorial Societies are common in North America and help consumers obtain reasonably priced funeral arrangements. Pre-paying services at a recommended funeral home allows us to leave funds with them for executor expenses, should our assets be frozen in probate. End-of-life insurance “add-ons” we like include travel protection—should we die away from home—and a final document service to close accounts and handle time-consuming administrative tasks.

In her book Advice for Future Corpses (and Those Who Love Them): A Practical Perspective on Death and Dying, Sallie Tisdale says, “Your body is the last object for which you can be responsible, and this wish may be the most personal one you ever make.” Traditionally in Tibetan Buddhism, the edict is to leave the body undisturbed for three days after death so your consciousness has time to disengage. Tisdale states that American law generally allows you to leave a body in place for at least 24 hours and that while a hospital might want to give you less time, you might be able to negotiate for more.

We then turned to the thorny topic of organ donation, with Rosie and Liv both deciding against. Knowing someone would soon be taking a scalpel to your cadaver would not enhance the peaceful mind they hope to die with, while my view was just the opposite. Besides gaining merit through donation, that same scalpel image provides great motivation to leave the body quickly.

While reading Tisdale’s chapter titled “Bodies,” I began entertaining thoughts of a green burial, but after months of discussion, I ended up where we all started: with expedient cremations. Rosie wanted her ashes buried and a fragrant rose bush planted on top. Liv and I were more comfortable in the water and decided our ashes would best be left there, but not scattered to ride on the wind. We selected biodegradable urns imprinted with tiny footprints. Made of sand and vegetable gel, they dissolve in water within three days, leaving gentle waves to lap our remnants out to sea.

By getting past the practical and emotional aspects surrounding death, Liv has found herself in a space of awe.

“There’s a wow factor to dying that I can now embrace,” she said.

Rosie no longer worries about who will care for her in later years. Without that insecurity, she’s left with a yearning to be as present for the dying process as possible. And I have found that my understanding of life’s importance as we reach toward enlightenment has been heightened.

Our small sangha still meets monthly and is now studying bardo teachings in our ongoing attempt to create compassionate dying from compassionate living. As we have continued with our arrangements, we’ve reflected on what we gained from our meetings. We feel blessed for the profound level of intimacy and trust we now share. We have a deeper regard for other friendships and feel enveloped by an enhanced sense of community. And we all feel more cared for.

As Chagdud Tulku Rinpoche wrote in Life in Relation to Death: “Putting worldly affairs in order can be an important spiritual process. Writing a will enables us to look at our attachments and transform them into generosity.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!