— Dying patient denied assisted dying in Catholic-run hospital

Sally wanted to die on her own terms. But despite voluntary assisted dying being legal in Victoria, her advocates say a Catholic palliative care facility obstructed access

By Melissa Davey and Donna Lu

When 60-year-old Sally* told her neurologist that she wanted to choose when to die, she was dismissed. Diagnosed with motor neurone disease, Sally knew her condition was incurable and that her rapid decline could include respiratory failure, difficulty swallowing and cognitive decline.

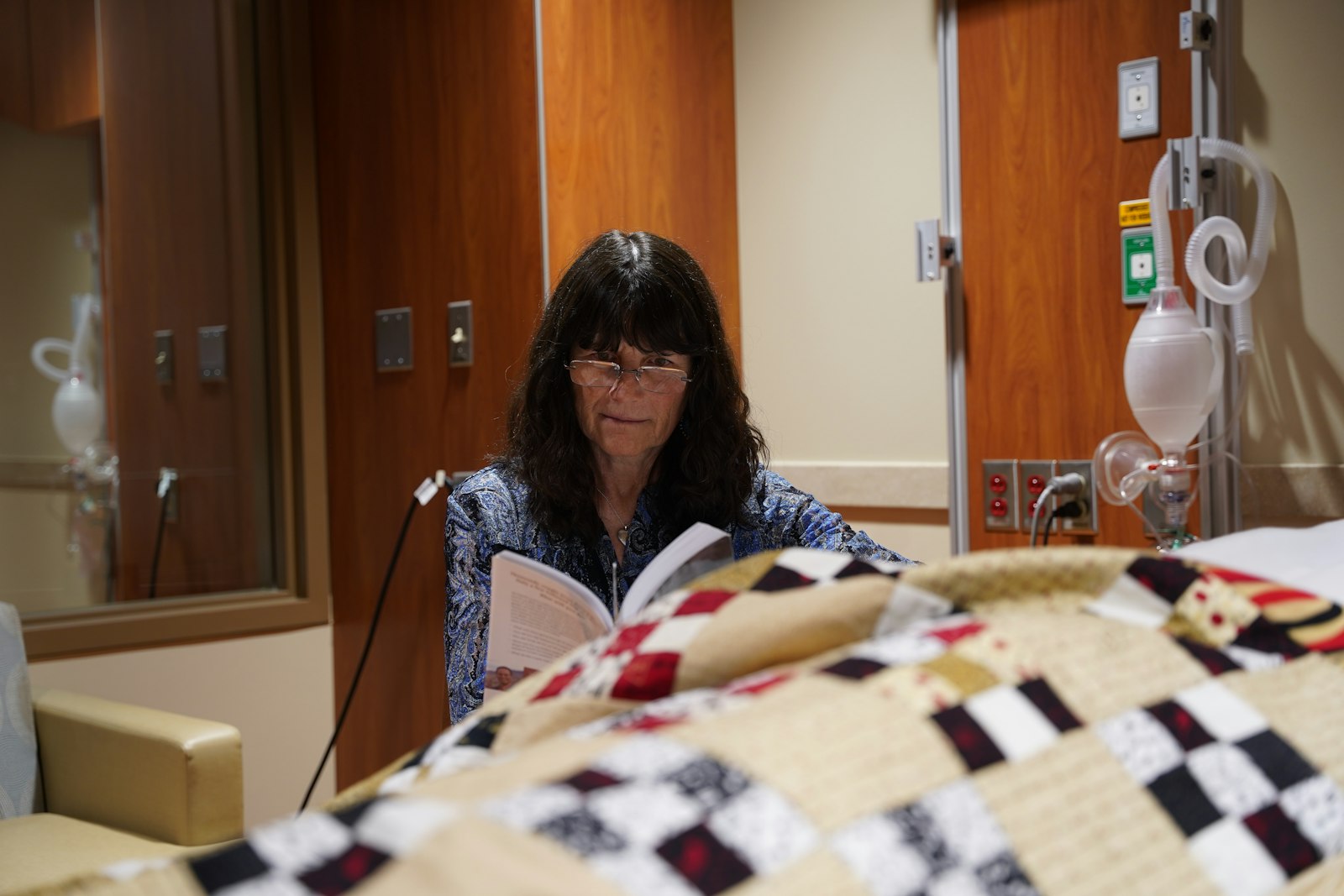

She wanted to die on her own terms, before her symptoms became unbearable. But Sally was receiving treatment at a Catholic palliative care hospital.

Sally lived in Victoria, where legislation allows those with neurodegenerative conditions such as motor neurone disease access to voluntary assisted dying. But her advocates say none of the doctors who diagnosed and treated her would provide the necessary paperwork for her to access euthanasia, nor would they refer her to someone who would.

Sally’s calls and emails to the hospital, an institution that objected to euthanasia, elicited promises of a response at a later date that never came.

“She had a terrible experience and she had to seek help outside of the hospital system,” says Jane Morris, the vice-president of Dying with Dignity Victoria. “She was one of the most lovely people I’ve ever met and it was cruel she was ignored or met with empty platitudes.”

By the time Morris met Sally, she couldn’t write and was communicating with a sight board. “She kept asking me to write down her story and tell it one day for her,” Morris says. “She told me that she wants voluntary assisted dying to be discussed openly, to be destigmatised and not subject to the religious doctrine of faith-based health facilities.”

Doctors and legal experts who spoke to Guardian Australia have called for voluntary assisted dying laws, which differ between the states and territories, to be nationalised and made more humane so that institutional objection does not lead to delays in care, or to patients dying in places they do not feel comfortable.

Depending on where someone lives, the catchment area they fall into may mean that the only local palliative care service is run by a Catholic organisation, which all have different policies about how they treat euthanasia. Under Catholic Health Australia’s code of ethics, any action or omission that “causes death with the purpose of eliminating all suffering” is not permissible.

Sally’s condition declines

The months of delays by the hospital would prove devastating for Sally. Her pain increased as her condition progressed, making it difficult to eat, speak and swallow. It meant taking the euthanasia medication orally was no longer an option, even if she was approved.

Desperate, Sally went outside the hospital system to a GP and asked for help. She was referred to the Victorian Voluntary Assisted Dying Statewide Care Navigator service, who helped her find a specialist and get the paperwork she needed, and she was put in contact with a voluntary assisted dying doctor trained to deliver euthanasia intravenously.

The doctor was not comfortable administering the medication outside a hospital and by the time she was approved, Sally was no longer well enough to travel to a health facility.

Plus, she wanted to die in her home.

When specialist doctor and voluntary assisted dying provider Eleanor* heard about Sally’s plight, she offered to help without hesitation. Eleanor assisted in getting approvals, travelled to Sally’s home and administered euthanasia drugs to her intravenously.

“I was sad and angry that she was delayed from accessing a service she had a right to,” Eleanor tells Guardian Australia.

“No one would write the letter that gave her access to voluntary assisted dying. She deteriorated very quickly and she lost the window in which she was well enough to comfortably go through the process in terms of going to doctor’s visits to get the approvals. So she needed to find doctors willing to come to her home. Unfortunately, cases like this are not rare.”

Sally’s situation was further complicated by federal legislation that prevents anyone seeking information or advice about voluntary assisted dying from a health professional over an electronic carriage service, ruling out telehealth consults for assistance. It is one of the reasons experts say uniform national legislation is needed.

Eleanor believes public funding for hospitals and aged care homes should come with a responsibility to provide a full suite of health services, including voluntary assisted dying.

“The alternative is sometimes to watch someone slowly suffocate to death, or die of a bowel obstruction, or starve to death because they can’t access a more humane way of dying,” she says. “We need national legislation to make the process more humane by taking the best of the legislation in each state and adopting it everywhere.”

It can also be difficult to find a doctor to administer or approve euthanasia drugs, with a shortage of trained voluntary assisted dying doctors, which Eleanor says is partly due to stigma and confusing legislation.

“Most doctors agree with voluntary assisted dying, but feel it is too hard to become a practitioner themselves.”

‘A huge power imbalance’

Victoria was the first state to pass voluntary assisted dying laws in 2017 and since then the other states have followed. In December 2022, commonwealth laws that stopped Australian territories from making new laws on voluntary assisted dying were repealed.

Three states – Queensland, South Australia and New South Wales – include institutional objection provisions in their legislation. Ben White, a professor of end-of-life law at Queensland University of Technology, says it means in those states, people are able to access voluntary assisted dying if they are a resident of an aged care or palliative care facility, even if the facility objects, because it is considered the patient’s home.

While conscientious objection by individual health professionals is protected by the Victorian legislation, objections by institutions are governed by their own policies, which White says aren’t always transparent. The Victorian health department has guidelines for how institutions can manage objections, but this is not binding. Health professionals are also barred in Victoria from raising voluntary assisted dying with their patients – the patient must bring it up first.

“I think we should be able to explain to people all the options they have,” says a health professional who has worked in end-of-life care for decades and did not want to be named. “I just believe in people being able to make informed choices – we’re talking about competent … people who already have a terminal illness.”

White agrees: “I think the key issue here is there’s a huge power imbalance.

“You’ve got people who by definition are terminally ill, expected to die shortly, trying to navigate and access voluntary assisted dying in a situation where the institution holds all the cards.”

In a study published in March, White and his colleagues interviewed 32 family caregivers and one patient about their experience of seeking voluntary assisted dying, including experiences with institutional objection. The objections described generally occurred in Catholic facilities or palliative care settings, which meant some or all of the euthanasia process could not happen on site.

Most commonly, patients were not allowed to meet with a doctor to be assessed; were prevented from accepting delivery of the euthanasia medication from a pharmacy; or were barred from taking the medication or having it administered to them.

White says it can leave families scrambling to transfer their loved ones elsewhere to die, including patients with conditions that made transportation painful.

One of the study participants said: “It will always be a great sadness for me that the last few precious hours on Mum’s last day were mostly filled with stress and distress, having to scurry around moving her out of her so-called ‘home’.”

There is a strong argument to limit the power of institutions to object to voluntary assisted dying when it harms patients, White says.

What Catholic hospitals could do

Oncologist Dr Cam McLaren says a component of cancer medicine is “fighting a losing battle and sometimes all you can do is choose the terms in which you die”.

It is why he became a voluntary assisted dying provider soon after Victorian legislation was introduced. “I was, and still am, in high demand and I have been involved in the assessment of about 300 voluntary assisted dying cases,” he says.

McLaren works for a Catholic hospital and says the values of religious organisations have “allowed them to do some incredible work in palliative care out of a desire to help people”.

He has helped facilitate the transport of patients off site to administer their euthanasia medication. He says different institutions have different levels of comfort with assisted dying and support certain “tiers” of access only; some allow doctors to consult with patients about the topic, but aren’t comfortable with the death occurring on site, for example.

“I completely support the ability of religious hospitals to refuse to be involved in practitioner administration of the drugs on site – that’s completely against their codes and morals,” he says.

“But a lot of the other steps in the process don’t involve any action. It’s just a conversation with a patient or information. And a discussion should not have the capacity to violate religious boundaries.

“I think a good model is for the hospital to allow the assessment and the delivery of the medication to the patient and then give patients time to plan to go home to have the medication administered there.”

But McLaren says this isn’t enough to protect patients in an aged care facility, where the facility is already home.

“And we have seen barriers in aged care homes overtly or covertly with non-assistance and noncompliance, so we have patients asking for months or weeks to access voluntary assisted dying and by the time they’re referred to me, it’s too late because the process takes time, which they don’t have.”

In NSW, voluntary assisted dying legislation will come into effect on 28 November, but there are still unanswered questions about barriers to access for patients being treated in religious public organisations.

People wishing to end their life in the state must be assessed by two doctors as likely having less than six months to live. A document seen by Guardian Australia detailing the response of Catholic health services Calvary Health Care, St John of God and St Vincent’s Health Australia to voluntary assisted dying suggests that these organisations will not allow assessments to be undertaken on site, with patients having to be transported elsewhere for the assessment or referred on to another hospital for care.

If a person has been approved for euthanasia to be administered by a medical practitioner, the document also outlines that the patient will need to go to another health provider or be discharged home. Doctors are concerned that these transfers may unnecessarily increase pain and suffering for patients at the end of their lives.

The document says “we do not abandon our patients” – if a person is considering or actively pursuing euthanasia, “our hospitals do not change our commitments to their provision of care”.

A spokesperson for Catholic Health Australia said on behalf of all three hospitals: “Our hospitals don’t provide [voluntary assisted dying (VAD)].”

“However, we recognise that some patients may wish to explore the option of VAD while under our members’ care. In that event, our services will never block or impede a person’s access to VAD if that’s their choice. Our services will always respect patient choice.

“When it comes to end-of-life, our members choose to specialise in palliative care. Other hospital providers choose to maintain an expertise in VAD. Transferring patients to a specialist provider when a service is not available is standard practice in the public health system.”

Dr Eliana Close, a senior research fellow at the Australian Centre for Health Law Research, has analysed institutional objection to euthanasia and says it is difficult to get data on how prevalent it is.

“We need to now see research and monitoring around how legislation in different states is unfolding and working in practice and whether rights are being respected,” Close says.

“We have certainly found we need stronger national laws to address that power imbalance between institutions and individual rights.”

Close says she finds it “completely abhorrent that publicly funded institutions should be allowed to deny access to legally available healthcare”.

“Not only is that causing harm to the patients in terms of pain and suffering, it’s causing harm to their families who have to witness it – and that has lasting impacts on their bereavement.”

* Names have been changed

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!