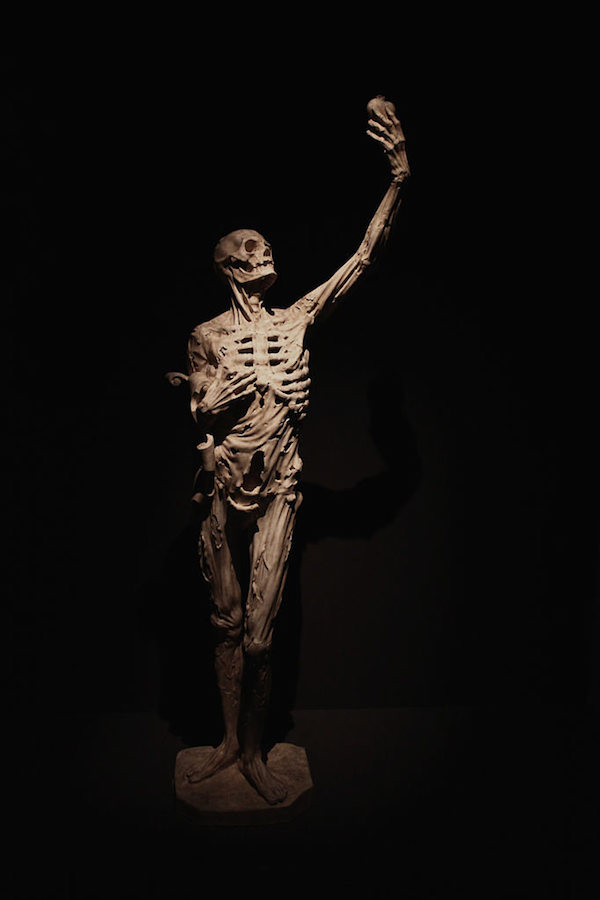

The Buddha said the greatest of all teachings is impermanence. Its final expression is death. Buddhist teacher Judy Lief explains why our awareness of death is the secret of life. It’s the ultimate twist.

by Judy Lief

[W]hether we fight it, deny it, or accept it, we all have a relationship with death. Some people have few encounters with death as they are growing up, and it becomes personal for them only as they age and funerals begin to outnumber weddings. Others grow up in violent surroundings where sudden death is common, or see a family member die of a fatal illness. Many of us have never seen a person die, while people who work in hospitals and hospices see the realities of death and dying every day. But whether death is something distant for us or we are in the thick of it, it haunts and challenges us.

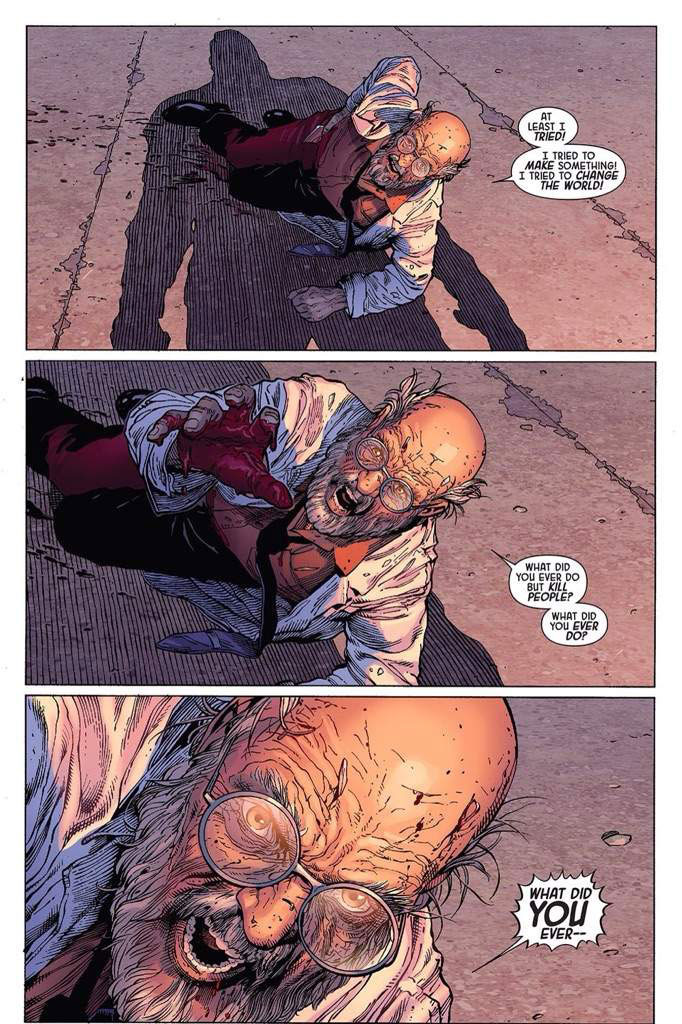

Death is a strong message, a demanding teacher. In response to death’s message, we could shut down and become more hardened. Or we could open up, and become more free and loving. We could try to avoid its message altogether, but that would take a lot of effort, because death is a persistent teacher.

Teacher death met up with us the minute we were born, and is by our side every moment of our life. What death has to teach us is direct and to the point. It is profound but intimate. Death is a full stop. It interrupts the delusions and habits of thought that entrap us in small-mindedness. It is an affront to ego.

Death is a fact. Our challenge is to figure out how to deal with it, because it is never a good plan to struggle against or deny reality. The more we struggle against death, the more resentment we have and the more we suffer. We take a painful situation and through our struggles add a whole new layer of pain to it.

We cannot avoid death, but we can change how we relate to it. We can take death as a teacher and see what we can learn from it.

Facts are facts: everyone is going to die sooner or later. No magic trick or spiritual gimmick will make it go away. Distancing ourselves from death or putting off thinking about it does not work.

I have noticed that the more distant we are from death, the more fear arises. Death becomes alien, other, scary, mysterious. People who work regularly with the dying, who are closer to death, seem to have less fear.

We each have our own unique relationship with death, our own particular history and circumstances, but one way or another we all relate to death. The question is: how do we relate with this reality and how does this color our lives? It is possible to come to terms with the fact of death in a way that enriches our lives, but to learn from death we must be willing to take a dispassionate look at our experiences and preconceptions.

Reflecting on our own mortality and the reality of death is practiced in many contemplative traditions. In the Buddhist tradition, the contemplation of death is said to be the “supreme contemplation.” It encompasses reflecting not only on physical mortality, but on impermanence in all its dimensions.

By means of meditation and by developing an ongoing awareness of death, we can change our relationship with death and thereby change our relationship with life. We can see that death is not just something that pops up at the end of life, but is inseparably linked with our life moment to moment, from the beginning to the end. We can see that death is not just a final teacher. It is available to teach us here and now.

When we contemplate in this way, our many schemes for getting around the reality of death, such as coming up with interpretations to make it more palatable, are exposed one by one and demolished. Death is the great interrupter, unreasonable and nonnegotiable. No amount of cleverness will make it otherwise.

Contemplating death is not an easy practice. It is not merely conceptual. It stirs things up. It evokes emotions of love, sorrow, fear, and longing. It brings up anger, disappointment, regret, and groundlessness. How tender it is to reflect on the many losses we have experienced and will experience in the future. How poignant it is to reflect on life’s fleeting quality.

How we think about death matters. It affects how we live our life and how we relate to one another.

In this practice, we deliberately bring our attention back again and again to our relationship with death. We examine what we mean by death and what it brings up for us. We reflect on our experiences and reactions to it.

It is a bit like going for marriage counseling. “When did you two first meet? Tell me a little about your history. Do you spend much time together? What is it about him or her that has offended you? How do you see your relationship moving forward?” You could say that death is your most intimate partner. It is with you all the time, completely interwoven into your daily activities. Since that is the case, wouldn’t it be worthwhile to make a relationship with it?

But our relationship with death is not that simple. In order to understand it, we need to slow down and systematically examine our ideas about it, what it brings up for us, and what it means to us. Death stirs up all kinds of thoughts. And hidden within those clouds of thoughts is a small, unspoken, deep-rooted, yet persistent notion—that we will come through it intact, as though we could come to our own funeral.

The more closely you look into all these ideas, the more you see how inadequate the conceptual mind is in the face of death. Nonetheless, how we think about death matters. It affects how we live our life and how we relate to one another.

Contemplative practice challenges us to look deeply into our thoughts and beliefs, our fantasies and presumptions, and our hopes and fears. It challenges us to separate what we have been told from what we ourselves think and experience. We have all kinds of thoughts about what happens when we die and how we and others should relate with death, but through meditation we learn to recognize thoughts as thoughts. We learn not to mistake these thoughts and ideas about death for direct knowledge or experience. We learn not to believe everything we think or everything we have been told.

We are in a dance with death at all levels, and each level influences and is influenced by the others. We are influenced by what we have been told about death and dying, by our personal history, by our cultural biases, and by what we have observed. We are also influenced by inner habits of thought and conditioned responses. Our most subtle views and reactions to impermanence may be quite hidden, but they touch on our view of life altogether, and on our personal identity.

If we want to understand our relationship with death, we need to explore its broader as well as its more subtle dimensions. If we are willing to take an honest look at how we personally deal with this reality, we can develop a deeper understanding of impermanence and even befriend it.

One way to begin is by reflecting on your personal history with death. What have you been told about death? What are some of your earliest experiences of it?

In my case, when I was about five, I was told my babysitter had died, and that was it. For me, she just disappeared, and children did not go to funerals. A bit later, when my aunt died, I was told that she would go to heaven, a very beautiful place. But I didn’t think people really believed that, because all I saw were people upset and crying. When pets died, I was told they “went to sleep.” It didn’t look like sleep to me.

As a child, I observed that dead animals did not breathe or move about like live ones. I saw that they shriveled up and began to smell funny, or were squashed beyond recognition. I saw that dogs hit by cars screamed in pain and that animals looked sick before they died. I saw that people became old and frail. I saw that when you killed a bug, you could not make it come back to life, even if you felt sorry. My friends and I thought it was funny to sing ditties, like “The worms crawl in, the worms crawl out…” Death was not that real to us; we made it into a joke.

I observed many such things on an outer level, but on an inner level, I did not have a clue as to what death was about or what it all meant. I did not know how to make sense of it, or to link it to other experiences in my life.

Death is the texture out of which we grow our identity, the stage on which we enact our story.

In our encounter with mortality, it is this inner dimension, the relationship dimension, that we need to explore. It becomes obvious that to get to a more uncluttered relationship with death, we first need to plow through a surprising number of ideas, presumptions, and speculations, some of which are very deep-rooted. Through this process, we can become aware of the many concepts that are floating around in us, and try to figure out where they come from and what effect they have on us.

When we look into where all this comes from, we encounter a paradox. We usually consider death to be the end, but it begins to seem that death is in fact the beginning. It is the texture out of which we grow our identity, the stage on which we enact our story.

We can begin our exploration right where we are. We have already been born, we are alive, and we have not yet died. Now what? We might connect to our life in terms of a story or a history. For instance, we were born in such and such a time and place, we did this and that, and we have a particular label and identity. But that story is always changing and in process; it is not all that reliable. However, when our story is combined with a physical body, we seem to have something more solid, a complete package. We have something to hang onto and defend. We have something that can be taken away.

But what do we have to hang onto, really? Our story is not that solid. It is always being revised and rewritten. Likewise, our body is not one solid continuous thing. It too is always changing. If you look for the one body that is you, you cannot find it.

The closer you look, the less solid this whole thing seems. When we investigate our actual experience, here and now, moment by moment, we see how fleeting and dynamic it is. As soon as we notice a thought, feeling, or sensation, it has already happened. Poof! It is the same with the act of noticing. Poof! Gone! And the noticer, the one who is noticing, is nowhere to be found. Poof! When we contemplate in this way, we begin to suspect that this life is not all that solid—that we are not all that solid.

This may seem like bad news, but in fact this discovery is of supreme importance. As we begin to see through our mythical solidity, we also begin to notice all sorts of little gaps in our conceptual schemes. We notice little tastes of freedom and ease in which our struggle to be someone dissolves, and we just are. In such moments, at least briefly, we are not being propelled by either hope or fear. We see that continually holding onto life and warding off death as a future threat is not our only option. There is an alternative to our tight-jawed habit of holding on and defending.

After each little insight or pause, there is a regrouping, and we find ourselves reconstructing our world. Each time we put it back together, we are also putting together the threat that it cannot be maintained. We do this over and over again. We are repetitively and continuously fueling the pretense of solidity and the fear of death that comes with it.

To undo this harmful habit, we need to see it more clearly. We need to recognize that we ourselves are responsible for perpetuating it, and therefore we have the power to stop.

In looking at the seeds of our relationship to life and death at a subtle inner level, we uncover how we set ourselves up for a struggle with death from the beginning—at the very personal level of identity and self-definition.

The more solidly we construct ourselves, and the more rigidly we identify with this construct, the more we have to defend and the more we have to fear. Looking at death in terms of such subtle underlying patterns may seem inconsequential, but it is not.

When we drop the battlefield approach—that life and death are enemies—we become open to an entirely new way of viewing things. Instead of this vs. that, us vs. them, something much more inspiring can take place. Experiences can arise freshly because they are immediately let go. Because they are dropped as soon as they arise, there is nothing to hold onto and nothing to lose. There is no battlefield, no winner and loser, no good guy and bad guy.

Simple formless meditation is a very powerful tool for relaxing this pattern of holding and defending. Working with death through our awareness of momentary arisings and dissolvings is a profound practice. It shows us that the life–death boundary is an ongoing and quite ordinary experience, and that this unsettling meeting point colors all that we do. If we can become more grounded at this level, we can become more open to what death has to teach us altogether.

Although death is an ongoing reality, there are times when it hits us particularly hard. It may be when we have a health scare or a near accident. At such times, we really wake up to the presence of death, and its teachings come through loud and clear. The heart pounds, the senses are heightened, and we feel extra alive. There is a stillness, as though time had stopped.

When we become complacent and take things for granted, death steps in.

Times like this are so simple and straightforward, so immediate. “This is it,” we think. “It’s actually happening.” In such moments, the heightening of our awareness of death simultaneously heightens our feeling of being alive.

In fact, in the face of death, we feel more fully alive than ever. We are shocked into thinking more seriously about what to do with the time that we have. Usually, though, we don’t maintain that awareness, and the feeling of heightened aliveness fades away. We revert to the default pattern of avoiding death, and, along with that, our dulled down approach to life.

Maintaining an awareness of death makes life more vivid. In the light of death, petty concerns fall away and our usual preoccupations become meaningless. It is as though clouds of dust that have covered over something shiny and vivid have been blown away, and we are left with something raw, immediate, and beautiful. We have insight into what matters and what does not.

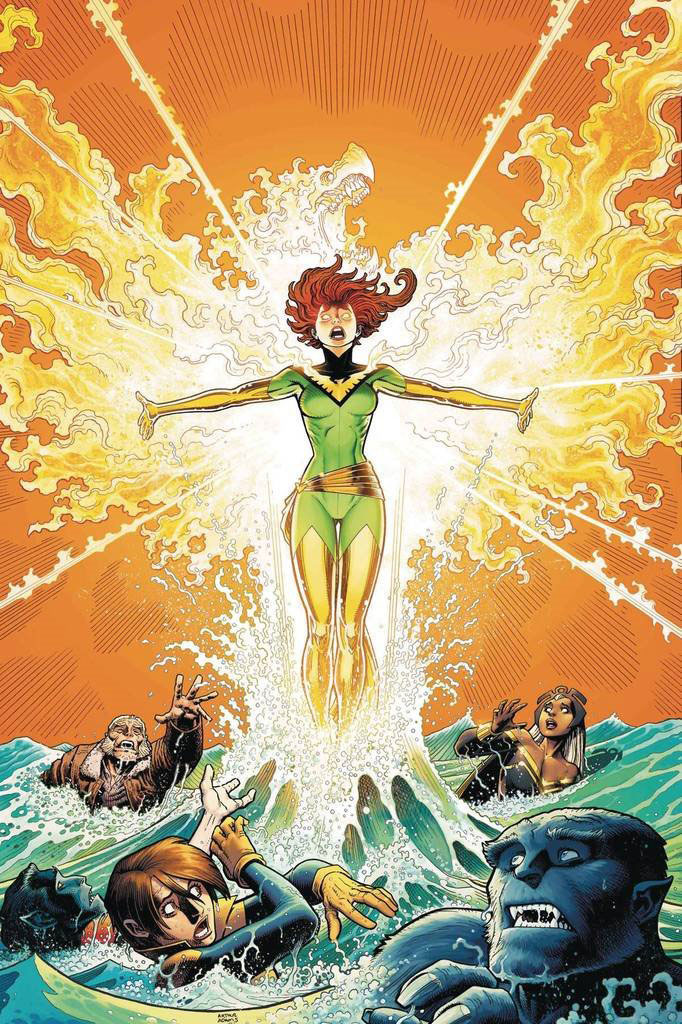

Awareness of death—hearing its teaching—cuts through the subtle clinging at the core of our experience. It cuts through our self-clinging and our clinging to others. This may sound harsh, but all that clinging has not really helped us or anyone else. Our clinging to others may have the appearance of real caring, but it is based on fear and an attempt to freeze and control life. It is a way of tuning out death and pulling back from the intensity of life. But if we develop more ease with our own impermanence and struggles with death, we can be more understanding of others and their struggles. We can connect with one another with greater genuineness and warmth.

Death turns out to be the teacher who releases us from fear. It’s the teacher that opens our hearts to a more free-flowing love and appreciation for life and one another. When we get stuck in self-importance and earnestness, death steps in. When we get caught in self-pity, death steps in. When we become complacent and take things for granted, death steps in.

Death spurs us forward with a sense of urgency and puts our preoccupations in perspective. Death lightens our clinging and mocks our pretensions. Death wakes us up. It is our most reliable teacher and most constant companion.

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!