End-of-life doulas fill an emotional gap between doctors, family and attitudes about dying.

By Kim Ode

[W]e should be better at dying.

That sounds judgmental, but it’s more akin to wishful thinking.

While death is a certainty, it’s rarely a goal, so we tend to resist, to worry, to grasp at new treatments or old beliefs.

But the emerging death doula movement offers another option: We can’t change the destination, but we can improve the journey.

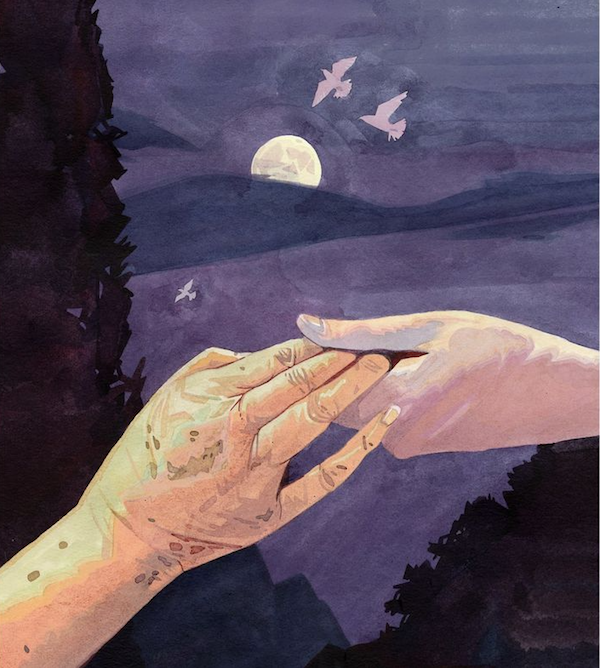

The term doula is more linked to childbirth, describing someone present during labor to help a mother feel safe and comfortable. There’s no medical role; doulas are companions and listeners. They attend.

End-of-life doulas, also called death doulas or death midwives, similarly are attuned to a dying person’s emotional needs.

“It’s about filling a gap that the system doesn’t acknowledge,” said Christy Marek, an end-of-life doula from Lakeville. “The system is designed to tend the body. But when you get into the lonely feelings, the mess of real life, the expectations and beliefs around dying — those things don’t fit into the existing system.”

In some ways, death doulas signal a return to earlier times, when ailing parents lived with children, when life-extending options were fewer.

“Death was more of a ritual, really laboring with someone as they were dying,” said Jeri Glatter, vice president of the International End of Life Doula Association (INELDA) in New Jersey.

Family and friends “felt a sense of acceptance and completion and a knowledge that they had fully honored someone,” she said. “It’s the most loving act that they could do.”

Over time, though, “we became a very medicated society — and thank God for that. I don’t want to diminish that,” Glatter said. But medical options can create a sense of disconnect with our inevitable mortality. When those options are exhausted, “we say we’ll house them, make sure they have medication and have a bed that goes up and down.

“But people are saying, ‘I don’t feel OK about this.’ ”

Marek is the first end-of-life doula in Minnesota certified by INELDA, credited with creating the first death doula program for hospitals and hospices in 2003. It offered its first public training in 2015; last year, 700 people attended 18 sessions. Several other groups in Minnesota and elsewhere offer training and doula directories.

Glatter said the trend has roots with those who used birth doulas in the 1980s.

“These people now are burying their parents. Just as with birth, as we labor into the world fully engaged in that process, they’re saying, ‘I want to be fully engaged in this process.’ Doulas are the bookends of life.”

How can we do this together?

What does it mean to be fully engaged? Whatever the dying person wants it to mean.

“Is the person having their own experience, instead of trying to meet the expectations of the family?” Marek asked. “I’m there to create a space for the person who is dying to ask, ‘How can we do this together?’ ”

One woman, for example, asked Marek to tell everyone that she wanted acknowledgment — a greeting — each time someone entered her room, “even though it may look like she’s sleeping.”

Marek added, “I have no agenda other than reflecting to that person what they are saying, what they are feeling. I can give directions to family and friends, which is a comfort to the dying person because then people around them know what to do — and they feel listened to.”

As part of a new field, doulas occupy a niche among doctors, family, hospice and other factors. Sometimes, doulas fill practical needs, gathering paperwork or helping with funeral plans, particularly if relatives are distant, either geographically or emotionally.

More often, though, their roles are more personal: creating a vigil environment, writing letters to loved ones, helping family members recognize the signs of dying such as a change in breath and, finally, helping survivors deal with their loss.

Glatter said that doctors or hospital personnel sometimes worry that a doula will infringe upon medical decisions. But doulas have no medical role, and may even be able to provide information that doesn’t come up in medical conversations, “such as, ‘Do you know there’s a son with a restraining order?’ ”

Doulas’ lack of medical standing also enables consistency. Doctors may change. Hospice care may be suspended. “But a doula provides a continuity of care no matter what treatments are being done or not,” Marek said.

Dying as a creative process

Marek, 47, appears to wear not a speck of makeup. The physical transparency mirrors her comfort with the emotions that dying can expose. But it took her years to reach this point.

With a degree in child psychology, she intended to work with youngsters. Then she met a child life specialist, a field of which she’d never heard, describing someone who works with children with acute, often fatal, illnesses.

“It was like a lightning bolt went through me,” she said. “I knew that someday I would work with people who are dying. And it scared the pants off me!”

She went on to do other work, in the course of which she explored yoga, shamanism, writing, painting and more. She studied to become an anam cara, from pre-Christian Celtic spirituality that translates as “soul friend.”

Every few years, the idea of working with dying people surfaced, but never took hold. Then, five years ago, she learned about applying doula principles to the dying process. This time, the idea came cast as “the creative process at the end of your life,” and her path was clear.

“I feel like this has been following me my whole life,” Marek said. She took the training through INELDA, which includes vigil planning, working with the survivors, and self-care for doulas themselves. She founded a business, Tending Life at the Threshold.

“As doulas, we’re trying to normalize the experience of death,” Marek said.

She recalled one woman who said that her mother would love it if Marek would read the book of Psalms or a Hail Mary. “And I told her, ‘I can certainly do that. But it would be more meaningful if you did.’ ”

Once family members and friends learn that it’s OK to “lean into the pain,” she said, they may find a sense of comfort and ease with dying that, in turn, proves a gift to their loved one.

Another support system

Karen Axeen had been sick for what seemed like forever, after years of breast cancer and ovarian cancer and other chronic illnesses.

After spending almost all of 2016 in the hospital, she decided to enter hospice care. She also decided that she wanted a doula at her side.

“She kind of fell into the idea, talking with the hospital social workers,” said her daughter, Laura Fennell, who lives in Marshall, Minn. “I don’t live close by, so I think it was really helpful for her.”

Working with Marek, Axeen developed what’s often called a legacy project. In this case, she wrote several letters to each of her six grandchildren, to be read as they grow older.

“She wrote letters to be read on their 16th and 18th birthdays, on their wedding days, on the first day they have kids of their own,” Fennell said.

“I think I probably would have been lost after my mom had passed away, but Christy had everything organized,” she added. “It’s definitely a great service for those who don’t have family in the area.”

End-of-life doulas “are another support system,” Fennell said. “It was important for Mom to be able to get to know someone closely and have them walk her through the final process of life.”

Axeen died on Sept. 23, 2017, at age 57.

‘We know how to die’

Some death doulas volunteer with hospices or churches. Others work in hospitals, while others set up private practices.

Glatter mentioned a California prison where inmates with life sentences became end-of-life doulas “because they wanted to be able to care for their own,” she said. “They’re really an extraordinary group of men who wanted to pay their debt to society by helping other inmates as they die.”

An article in Money magazine included death doulas among “seven new jobs that reflect what’s important in 2017.” Also listed, compost collectors and vegan butchers.

The death doula trend reflects gradually more open attitudes toward death. Surveys show that 80 percent of Americans would prefer to die at home if possible, but few are able to. Yet the landscape slowly is changing. Hospital deaths slowly declined from 2000 to 2010. In that time, deaths in the home grew from 23 percent to 27 percent. Deaths in nursing homes held steady at about 20 percent.

The Centers for Disease Control suggested that the shifts reflect more use of hospice care. As the dying process becomes, for some, more grounded in the home, end-of-life doulas may become more familiar and, in Marek’s vision, help make death a natural part of life.

She reached that vision, in part, during an outdoor meditation project she began in 2014. For 1,000 days, she meditated for 20 minutes outdoors, no matter the weather. (It’s on Instagram as wonderofallthings.)

“Sometimes I’d be thinking, ‘This is awful. But that’s OK,’ ” she said. “It helped me develop a tolerance for whatever is happening, and to stay close to the fact that none of us is immune to the cycles of nature, including death.

“If you can sit when it’s uncomfortable — to be able to sit in the unknown — that’s huge.”

While family members may not be at peace with someone’s death, she added, they can be at ease with it as a natural outcome of life.

“One thing I believe firmly is that we know how to do this,” she said. “We know how to die, like every creature of nature does. We just need to get out of our own way.”

Complete Article ↪HERE↩!