By April Dembosky

Three terminally ill patients lost a court battle in California Friday over whether they should have the right to request and take lethal medication to hasten their deaths.

San Diego Superior Court Judge Gregory Pollack said he would dismiss the case, adding that the issues were beyond his role as a judge to decide and should instead be put to the California state legislature or voters to establish new law.

Plaintiffs vowed to appeal the ruling.

“This is certainly frustrating, but it’s a temporary setback,” said Elizabeth Wallner, a plaintiff in the case, who has been diagnosed with Stage IV colon cancer. “I am optimistic that we’ll prevail in the end. It’s too big of an issue to leave uncovered.”

Wallner began a series of treatments for her cancer in 2011, including surgeries to remove her colon and parts of her liver, radiation, and numerous rounds of chemotherapy. In the midst of this, when her son was 16, she realized that she wanted to have control over her own death.

“I was throwing up in the bathroom and my son was taking care of me,” she said. “I looked over at his face and I saw him absolutely stricken, watching his mother experience this. I thought, that’s enough — my son doesn’t need to see this. I should have the right to make that decision when it’s time.”

The case she and others brought to the court seeks to challenge current California law (Section 401 of the state penal code), which makes it a crime to deliberately aid or advise another person to commit suicide. Wallner and the other patients say the law prohibits their doctors from discussing or prescribing medications that could end their lives; and that prohibition, they say, violates their rights to privacy, liberty, and free speech under the California Constitution.

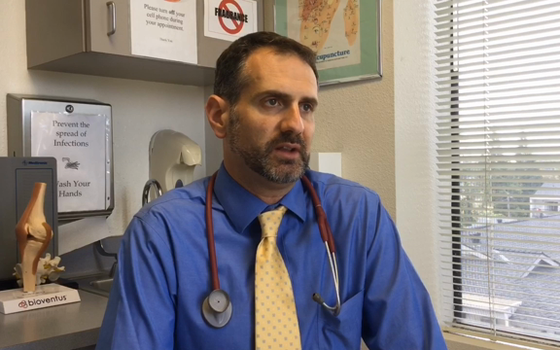

Attorneys for the plaintiffs — the three patients and a physician — argue that the option to hasten death is an extension of previously recognized legal rights to make end-of-life decisions, including the right to refuse life-sustaining treatments, like a feeding tube or ventilator.

“When you’re suffering, and you know you’re going to die anyway, it should be up to you to decide when enough is enough,” said Kevin Diaz, an attorney and director of legal affairs for the advocacy group Compassion & Choices, which is representing the plaintiffs. “We’ll keep trying anyway we can to make sure this is an option.”

But California Attorney General Kamala Harris, one of the defendants in the case, argued that there is no right to assisted suicide embedded in California law. Health statutes that protect patients’ rights to withdraw treatment, Harris said, do not include a right to provide proactive assistance to end someone’s life.

“No court has ever extended the right to privacy to encompass an affirmative medical intervention to kill oneself,” Julie Trinh, deputy attorney general, wrote in a legal brief.

She wrote that while the court has sympathized in the past with the plight of the terminally ill, it concluded that the question of allowing physician-assisted suicide is a legislative matter, rather than a judicial one.

The judge in this case agreed. He said he would issue a formal ruling on Monday.

A bill that aims to legalize physician-assisted suicide in California (SB 128) has been tabled for the rest of the year, after stalling in the Assembly Health Committee. Several attempts in other states to pass a similar bill this year have failed.

The practice is legal in five states: The courts authorized the practice in Montana and New Mexico; Vermont passed a law in its legislature; and voters approved ballot measures in Washington and Oregon.

There is one other lawsuit pending in California.

The three patients who are plaintiffs in the case dismissed Friday are worried that the legal process will be too slow to provide relief for them. Christy O’Donnell, a single mother from Santa Clarita, Calif., who is dying from lung cancer, explains her situation in the video below, released earlier this year.

Complete Article HERE!