When a friend asked me to accompany him to an organisation that provides assisted suicide, I trusted my feelings would catch up with my desire to help

By Steven Amsterdam

I had nearly finished writing a novel about a dying assistant (not an assistant who is terminally ill; a person who hands over the necessary overdose of Nembutal) when I had a fateful conversation with an old friend.

Russ, who had long been sick, asked if I would go with him to Dignitas in Switzerland – a nonprofit organisation that provides assisted suicide – to help him die.

He said, “It’ll be good for your book.”

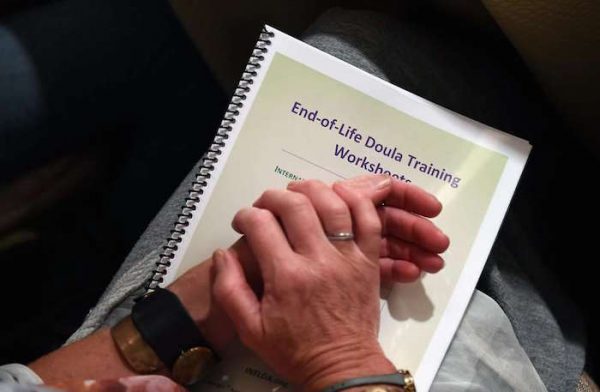

I’m a palliative care nurse, so I am all for a good, comfortable death. The nursing work is the reason I wrote the book – to imagine how such a character gets through their life and why. But Russ was not asking for creative writing. After three years of co

“Come on,” he said. “You should write about it. Plus, I’ll need a nurse for the endgame.”

I said “yes” because I trusted that my feelings would catch up with my desire to help my friend.

Almost 30 years ago Russ and I were briefly housemates in Brooklyn. He was a grad student in Icelandic mythology, stringing fellowships together and living mostly at the library, or in Reykjavik.

A few years later, when he was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis, he left the ancient world for better health insurance and became an academic editor. He battled on after that – with accessible keyboards, accommodating work hours and, finally, handrails and ramps – until he couldn’t manage anymore. “Retired” at age 40, his world scaled down to a few far-flung friendships and to his studio apartment in Queens.

Last year, a series of seizures – “wrecking balls”, Russ called them – abruptly took away function of just about everything but his left hand. Unable to transfer from bed to wheelchair, much less prepare food, he became reliant on public benefits and a shrinking bank account. To get by, he needed an ever-changing array of aides. Underpaid and undertrained, they thoughtlessly bullied, yakked and dropped him. To preserve a semblance of solitude, he limited their assistance to a few hours a day.

I live in Melbourne, so I was useful for middle-of-the-night calls. “That’s not nothing,” he said. When he was both dreading and needing the next aide, when he couldn’t reach the water on his end table, or when his mind was not being kind to him, we talked. A closer circle of friends or family or a better healthcare system could have helped but they weren’t an option. He was trapped in his bed, alone and crying.

“We always knew I wouldn’t do well when it got like this. I never expected it would be so soon.”

He told me last August he wanted to be dead before Christmas and that I would be the ideal escort. My patients have taught me how to discuss death without the usual terror, which lent me cred. Writing the novel had given me more than a casual understanding of all that would be involved. And after watching Terry Pratchett’s documentary about accompanying someone to Dignitas, I even knew my way around the Ikea-plain apartment where it would happen.

For me, the experience would be nursing education. It would be research for the book. And, as Russ pointed out, the flight to Zurich would be tax-deductible.

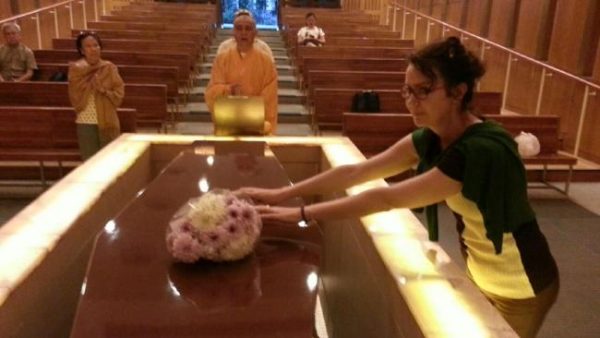

The application to Dignitas was his last writing assignment. For weeks, Russ fine-tuned his one-page statement on why he wanted to die. Another friend helped locate and notarise all of the required documents – confirming identity, prognosis and state of mind. She and I would accompany him, so that neither of us would have to fly back alone.

While Russ waited, he revised his will, gave his belongings away and, with heartbreaking care, explained to his 10-year-old niece why he wanted to die.

The letter finally came in December, outlining the final bits of protocol. For me, the letter was a doorway: I knew I would be ready to help him die. For Russ, it was something else: the planning stopped. He seemed to relax into his situation at home. He didn’t embrace it but, when he described an aide’s latest screw-up, I heard less rage and more acceptance of what was happening to his body. He stopped talking about dying as often or as urgently. There were fewer late-night calls. And, when we talked, it was about my edits and not his panics.

Dignitas were asking for too many documents, he said. Or Zurich would be too cold this time of year. Or this: “It’s too big a trip to make if I’m going to chicken out.”

It seemed as if what he had wanted was acknowledgement that he had been dealt a crap hand. With the official affirmation from Dignitas, he could go on playing it.

Then, last June, nearly a year after he first voiced the wish, the plan was on again. He would go in July. “I’m not cheerful about it but I don’t see another way.” The friend who’d helped with so much of the paperwork and another friend – one he’d had little contact with but who lived nearby – would go.

Not me.

“You live too far away,” was all he said, though the distance hadn’t been an issue before.

I imagine there’s a long word in Icelandic to describe the unique whiplash that comes from psyching oneself up to emotionally support a suicide and then suddenly being excluded from the project. Was it really logistics? I checked back over our conversations for some offence. Did I show too much writerly curiosity? Too much nursey pressure? Was he simply protecting me from the moment in the Dignitas apartment that neither of us could picture?

Russ made the trip and died two months ago. When I heard that he was resolved and relaxed in his last hours, I stopped speculating why I wasn’t there. It wasn’t about me.

The grief I’m left with has mostly been the completely ordinary and uncanny kind – life goes on without him. We lived apart for so long that my daily routine is untouched. It’s when I think about the conversations we’ll never get to have that I feel the loss. At times though, it gets more complicated. The anger is not at his quick death but at the long disease that led him to a place where he couldn’t see another way. Suicide – for lack of a better word – serves as a reminder that life is not only finite, it’s optional. What do we do about that? I don’t pretend to know.

More recently, a different feeling has washed up, requiring another long word in a strange language to articulate. It would cover every part of this past year with Russ: the wrecking balls, the plan, the new plan, his death and its aftermath. The word would mean three things at once and it would apply to both of us: a door tightly closed, a mercy granted and a bullet dodged.

So here, Russ: I wrote about it.

Complete Article HERE!