- After almost 20 years of living with a pacemaker, Nina made a decision

- Ms Adamowicz, 71, no longer wanted the device that was keeping her alive

- After some consideration doctors agreed, and the woman died peacefully

- Thought to be the first case in the UK, their choice has sparked controversy

By Rachel Ellis

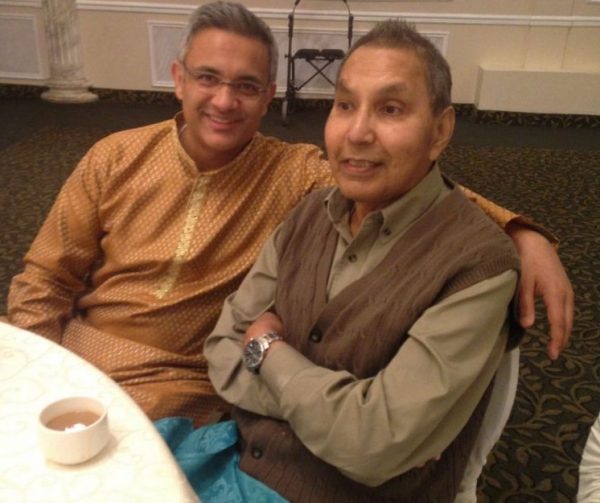

[A]fter almost 20 years of living with a pacemaker, Nina Adamowicz decided she no longer wanted the device that was keeping her alive.

It had been implanted in 1996, and for the first decade it ‘improved’ her life and symptoms — she had a form of hereditary heart disease.

The pacemaker sent regular electrical pulses to keep her heart beating steadily, and she was grateful for ‘being given extra time’, she later recalled.

However, she then had a heart attack and her health declined so that by 2014, her heart was working at just 10 per cent of its capacity.

Last year, Polish-born Ms Adamowicz, 71, who had lived in the UK for more than 30 years, revealed she wanted the pacemaker turned off, even though she knew it would lead to her death.

It was like being ‘in line for execution and being told “not yet”, she said in an interview for BBC Radio 4.

‘It’s not about “I want to die”, I’m dying,’ she added.

After a series of medical examinations and psychological tests to determine whether she understood what switching off her pacemaker would mean, doctors agreed, and last October Ms Adamowicz went into a local hospice with her family for the pacemaker to be turned off – a procedure that took 20 minutes.

She described her body as feeling heavy and she felt a little nauseated – but she also felt at peace, her family told the BBC.

She slept through the night, returned home in the morning and died that night.

Her case – thought to be the first of its kind in the UK – raises profound ethical issues about when it is right to turn off someone’s pacemaker, or indeed withdraw other medical treatment such as dialysis for kidney failure, if that’s what they want.

In fact the law itself is very clear on this point, according to Miriam Johnson, professor of palliative medicine at Hull York Medical School.

‘A mentally competent adult has the right to refuse medical treatment, whether it is turning off a pacemaker or stopping dialysis, even if that treatment is prolonging their life and withdrawing it will lead to their death,’ she says.

‘By turning off the device, the disease or illness will kill the person, not the doctor.’

However, some doctors feel it’s uncomfortably close to euthanasia — the difference is that euthanasia involves overriding Nature.

‘The difficulty with a case like this is that when a patient is dependent on a pacemaker, there is a direct connection between withdrawing the treatment and them dying within the next few hours,’ adds Professor Johnson, explaining that doctors’ role after all is to protect the vulnerable.

Around 35,000 patients in the UK have a pacemaker fitted each year. The device’s role is to keep the heart beating steadily – it gives it a boost by delivering electrical impulses so that the heart contracts and produces a heartbeat.

The computerised match-box sized device is implanted just under the skin, usually just below the left shoulder and electrical leads are then fed down a vein into the heart.

‘In a significant number of pacemaker cases if you suddenly took the pacemaker away, the heart would stop beating,’ explains Dr Adam Fitzpatrick, a consultant cardiologist and electrophysiologist at Manchester Royal Infirmary and Alexandra Hospital, Cheadle.

He adds: ‘It is very unusual for a patient to ask for their pacemaker to be turned off.’

Even if the patient is dying, a pacemaker does not need to be switched off, says the British Heart Foundation.

‘Its purpose is not to restart the heart and it won’t cause discomfort to someone who’s dying,’ said a spokesperson.

But the picture is slightly different with other heart devices such as Implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) which are used to correct an abnormal heart rhythm rather than helping the heart beat steadily.

These devices, implanted in around 9,000 people in the UK every year, kick in when an abnormal heart rhythm occurs which can cause sudden cardiac arrest (where the heart stops beating).

Implanted under the collarbone as a pacemaker is, they work by firing a small electric shock into the heart to kick-start it (some pacemakers have this function too).

This might happen once every few months or not even for years.

However, this can be both painful and traumatic, especially at the end of life, and can lead to a prolonged and distressing death by continuing to give electric shocks.

In one particularly upsetting case reported in a US medical journal, a man suffered 33 shocks as he lay dying in his wife’s arms — the ICD ‘got so hot that it burned through his skin’, his wife later reported.

‘Dying patients often have multi-organ failure which can cause metabolic and chemical changes that may trigger arrhythmias, faulty heart beats and in turn activate the ICD,’ explains Dr James Beattie, a consultant cardiologist at the Heart of England NHS Foundation Trust, Birmingham.

‘If the device goes off when the patient is conscious, the shock is like a blow to the chest, causing discomfort and distress. It may also fire repeatedly.

‘This may result in a distressing death for the patient and distress for the families.’

Yet despite this suffering, 60 per cent of hospice patients do not have their implant deactivated before death, according to U.S. research published in the Annals of Internal Medicine.

Furthermore, a 2011 survey by the National Council for Palliative Care suggested that only 40 per cent of UK hospices have access to the technology to deactivate the device urgently, potentially risking an undignified and painful death in hundreds of patients should they suddenly deteriorate.

Switching off the device involves holding a magnet over it, temporarily closing a magnetic switch incorporated in it.

To turn it off permanently the device has to then be reprogrammed remotely using a ‘wand’ attached to a computer.

Medical professionals and families face a number of dilemmas when deciding whether to turn off an ICD.

One is the difficulty in accurately predicting when the patient is reaching the end of their life.

‘Determining this isn’t always clear, especially with a condition such as heart failure when patients may have survived crises over many years,’ explains Professor Johnson.

‘This can be complicated further if the patient is suffering from dementia and unable to make decisions about their care.’

There is also an understandable reluctance by patients and their families to take away anything that can prolong life.

‘Patients and their families frequently think of the device as entirely beneficial,’ says Professor Johnson.

‘There is also often unrealistic expectation about what doctors are able to do to keep people alive.’

Many doctors shy away from these conversations, too. A 2008 report from the National Audit Office found a significant lack of confidence in handling end-of-life care across all medical specialities — with cardiologists topping the league.

‘Given they are trained to save lives, talking about death can be seen as professional defeat,’ says Dr Beattie.

But if patients and doctors don’t have that conversation ‘we’re storing up trouble because decisions then have to be made at times of crisis and without planning’, says Simon Chapman, of the National Council for Palliative Care.

New guidance for patients and medical staff to guide them through the ethical minefield of withdrawing heart devices was published earlier this year in the journal Heart.

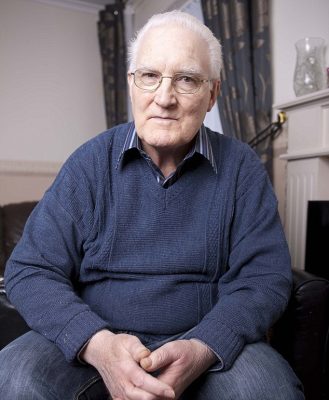

Just how difficult making such decision can be was dramatically highlighted in the case of Fred Emery.

When his health suddenly went downhill six years ago, doctors recommended turning off the defibrillator that had been keeping him alive for the past 14 months.

The 73-year-old former manual worker from Kings Langley, Hertfordshire, had had the matchbox-sized device implanted in his chest following a 26-year battle with heart disease.

During that time he’d had two heart attacks, and had already undergone two triple heart bypass operations as well as having several stents (tiny metal tubes) inserted to prevent his arteries blocking.

However, Fred then developed heart failure and ventricular tachycardia — a potentially fatal heart rhythm

Having a defibrillator not only helped with the heart failure, but also any sudden cardiac arrest triggered by the faulty heart rhythm.

But Fred’s condition deteriorated and doctors suggested that as he was nearing the end of his life, it was time to turn off this life-line — to spare him and his family the ordeal of it repeatedly jolting his heart back to life when his body had reached the natural moment of death.

However, despite doctors’ predictions, Fred pulled through and later had the defibrillator reactivated, and it went on to save his life several times before his death this year. His family was angry that doctors had written him off before his time.

‘It was awful when they told him to turn it off,’ his wife Shirley, 70, told Good Health. ‘Fred was taken ill at 4pm, and by the next morning the defibrillator was turned off. It was too soon to make that decision — he wasn’t himself and was under pressure to switch it off.

‘After it was reactivated, Fred had six more years. Without the ICD we would have lost him several years ago.

‘He kept it on until a week before his death. By then his heart was working at 15 per cent, he was in a hospice and there was no coming back so we made a decision to turn it off to give him some dignity at the end. He knew what was happening.